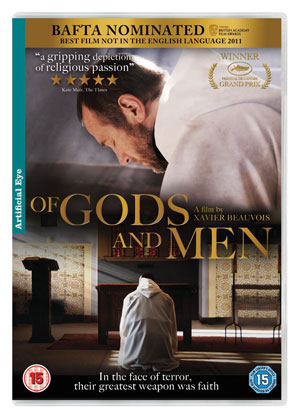

Xavier Beauvois, Of Gods and Men

Love conquers all … even death

“Remember that love is eternal hope. Love endures everything.”

IN THIS DAY and age of mindless blockbuster cinema, reality TV and glossy, box-setted dramas running into hundreds of episodes, it is a refreshing relief to discover a film so compelling, understated and meaningful that it restores your faith in the silver screen and, more importantly perhaps, your belief in a higher power.

Directed by Xavier Beauvois (born 20th March 1967), Of Gods and Men (Des Hommes and Des Dieux) tells the true story of a brotherhood of monks from the Abbaye Notre-Dame de l’Atlas, the Roman Catholic Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (known as Trappists) located in Tibhirine, a benign remnant of French colonialism situated in the Atlas Mountains of Algeria.

Set amidst a Muslim community, they live together in peace and harmony, helping and sustaining each other’s way of life, until seven of the monks are kidnapped and assassinated by Islamic fundamentalist terrorists. The film has won many critical accolades, including the prestigious Grand Prix at the 2010 Cannes Films Festival.

Je l’ai dit: Vous êtes les dieux, les fils du Très-Haut, vous tous! Pourtant, vous mourrez comme des homes, comme les princes, tous vous tomberez!

I have said, Ye are gods; all of you are children of the Most High. But ye shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes.

—Psalm 82:6-7

In classic French cinematic style, reminiscent of Philip Gröning’s Into Great Silence (a documentary based on the lives of Carthusian monks of the Grande Chartreuse, high in the French Alps), the film is slow-paced, lingering on the seemingly mundane detail of the monks’ daily routine—eating a meal, making honey, singing psalms, washing the floor—creating a mood of profound order and stillness. As there is no accompanying musical score, we are immediately drawn to the quotidian sounds of a church bell, birdsong, the rustle of a monk’s habit, a dog’s bark.

Photograph: Sony Pictures Classics

Love conquers all

In an early scene, a young woman helping out in the dispensary and reflecting on her emotional life, asks Frère Luc (played by Michael Lonsdale) how you can tell when you are in love:

There’s something inside of you that comes alive. The presence of someone. It’s irrepressible and makes your heart beat faster, usually. It’s an attraction, a desire. It’s very beautiful. No use asking too many questions. It just happens. Things are as usual, then suddenly happiness arrives, or the hope of it. It’s lots of things. But you’re in turmoil. Great turmoil. Especially the first time.

She then asks if Frère Luc has ever been in love:

Several times, yes. And then I encountered another love, even greater. And I answered that love. It’s been a while now. Over 60 years.

The love between the monks is genuine and palpable; small gestures reiterate the bond of affection they all have for one another—a gentle massage of the shoulders, a reassuring pat on the back. In one particularly moving scene, where the monks are being intimidated by a low-flying helicopter outside the chapel, they all form a semi-circle, holding each other defiantly by the arms, steadfastly continuing their daily chanting of the psalms.

Photograph: Sony Pictures Classics

Accept the consequences of your choices

The mid-1990s were a time of political upheaval in Algeria; roving Islamic fundamentalist militants were targeting foreign nationals throughout the land. We first witness the slaughter of a group of Croatians, and their deaths form the haunting backdrop to the apparent tranquillity of the abbey. As the film progresses, we witness fraught scenes between the monks and the Algerian security forces, who believe they are in league with the militants.

This leads the head of the order, Frère Christian, to ask his fellow brothers whether they should leave the monastery for the sake of their own personal safely. Each monk must reflect deeply into their own conscience on their motives for staying or leaving, and how it will subsequently impact on their faith.

In a touching scene on a hilltop above the monastery, Frère Christian (Lambert Wilson) and Frère Christophe (Olivier Rabourdin) discuss the weight of the dilemma they find themselves in and how it is taking its toll:

Frère Christophe: I sleep badly. The slightest noise wakes me. I think over my life. My choices … Dying for my faith shouldn’t keep me up nights. Dying here, here and now, does it serves a purpose? I don’t know. I feel like I am going mad.

Frère Christian: It’s true that staying here is as mad as becoming a monk. Remember. You’ve already given your life. You gave it by following Christ, when you decided to leave everything. Your life, your family, your country, the family you could have raised.

Frère Christophe: I don’t know if it’s true anymore. I pray. And I hear nothing. I don’t get it. Why be martyrs? For God? To be heroes? To prove we’re the best?

Frère Christian: No. We are martyrs out of love, out of fidelity. If death overtakes us, despite ourselves, because up until the end we shall try to avoid it, our mission here is to be brothers to all. Remember that love is eternal hope. Love endures everything.

They embrace. Later, in a vote at a chapter meeting, the monks unanimously decide to stay. For the following three years, the group of eight brothers live in fear for their lives.

Photograph: Sony Pictures Classics

No man can escape death

In one of the final, most poignant scenes of the film, sensing the end is coming, the monks partake in a symbolic Last Supper, drinking red wine and breaking bread in the refectory, to a cassette recording of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. The camera pans around the table, resting on the faces of each monk; the look of resignation to their fate is utterly heart-rending. During the night (26th–27th March 1996 to be precise), the monastery is raided, seven monks are bundled into the back of a van, and they are driven away.

In late May 1996, the heads of seven brothers were found far from Tibhirine; what actually happened to them has never been established. The two surviving monks, who were in separate rooms at the time of the abduction and escaped the kidnappers’ notice—one who was the remaining resident of the abbey; the other, a visiting monk—have subsequently left Tibhirine and established a Trappist monastery near Midelt in Morocco.

The final scene depicts the monks being marched through a snowstorm along a mountain pass by their captors, struggling to come to terms with the fact that they are walking towards certain death. Indeed, Of Gods and Men is produced with such subtlety and sensitivity, the dénouement of the film is all the more devastating.

As the monks disappear into the enveloping blizzard, an anonymous letter is read by one of the monks:

Should it ever befall me, and it could happen today, to be a victim of the terrorism swallowing up all foreigners here, I would like my community, my church, my family, to remember that my life was given to God and to this country.

The Unique Master of all life was no stranger to this brutal departure. And that my death is the same as so many other violent ones, consigned to the apathy of oblivion.

I’ve lived enough to know that I am complicit in the evil that, alas, prevails over the world and the evil that will smite me blindly. I could never desire such a death. I could never feel gladdened that these people I love be accused randomly of my murder.

I know the contempt felt for the people here, indiscriminately. And I know how Islam is distorted by a certain Islamism. This country, and Islam, for me are something different. They’re a body and a soul.

Photograph: Sony Pictures Classics

My death, of course, will quickly vindicate those who called me naïve, or idealistic, but they must know that I will be freed of a burning curiosity and, God willing, will immerse my gaze in the Father’s and contemplate with him his children of Islam as he sees them.

This thank-you which encompasses my entire life includes you, of course, friends of yesterday and today, and you too, friend of the last minute, who knew not what you were doing.

Yes, to you as well I address this thank-you and this farewell, which you envisaged. May we meet again, happy thieves in Paradise, if it pleases God, the Father of us both.

Amen.

Post Notes

- Assassination of the monks of Tibhirine on Wikipedia

- Of Gods and Men official website at Sony Classics

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- Ismaël Ferroukhi: Le Grand Voyage

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Victor Kossakovsky: Gunda + Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier: The Velvet Queen