The ten oxherding pictures and verses

“We’re all in this music of communication together.”

STEPHEN NACHMANOVITCH is a highly accomplished musician, specializing in composing and performance, as well as the author of seminal classics, Free Play and The Art of Is, books that explore the inner sources of spontaneous creativity. An eternal lover of the arts, he has also had a long-time engagement with spiritual practices, specifically Zen and Eastern philosophy.

In this month’s guest post for The Culturium, Stephen gives an insight into his creative processes with particular regard to his composition, Taming the Mind Ox, a musical and visual response to the immortal ten oxherding pictures by Tenshō Shūbun, with verse translations by D. T. Suzuki.

When I was a child in Los Angeles, my mother used to kiss trees when she thought nobody was looking. (She would look back at me with a sheepish smile when she did it, saying that people would think her crazy.) She used to talk about God quite fluently, as Einstein did, perceiving a unity and beauty in the universe. Both my parents were Depression-era high-school dropouts but my mother read everything—novels, plays, poems, philosophy. As I would sit on a stool in the kitchen watching her cook, she went into these philosophical-spiritual stream-of-consciousness riffs about justice, beauty, love, compassion, art.

I was going to be a scientist when I grew up. The first piece of writing I ever published was in the Journal of Protozoology. I was stereotyped as a science nerd in school but I always had this fascination with literature, philosophy, history, all sorts of things. I loved music and played the violin since the age of seven, though not terribly well, and was in orchestras. As I went through school and university, I moved “from” hard sciences “to” biology to anthropology to psychology to the study of play, to the study of visionary art and creativity. I kept looking for “where it’s at” —the most central questions, not really moving “from” or “to” but it was seen that way by others. It wasn’t until last year, at age 73, that I coined the word holomath—to describe people who are interested in lots of things not as separate fields but as manifestations of a bigger pattern. [Read Stephen’s article, Being Whole, where he coins the term holomath.]

Over many years, I was blessed with mentors and people who encouraged me along the way: Irven DeVore, Jerome Bruner, Abdul Aziz Said, Yehudi Menuhin, Pauline Oliveros, among many others. And above all, my beloved friend and mentor, Gregory Bateson. Bateson took the spirit of my mother’s tree-kissing to a high intellectual level—we’d walk in the redwood forests and tide pools of Northern California, paying exquisite attention to the plants and animals, paying exquisite attention to context and to their strong and delicate interdependencies. (Perhaps God is a way of talking about those patterns of interdependencies and the pattern of patterns of patterns.) Gregory sat me down and confronted me with the work of William Blake. Blake talks about the creative process in such a way that you can’t merely study it, you have to do it yourself.

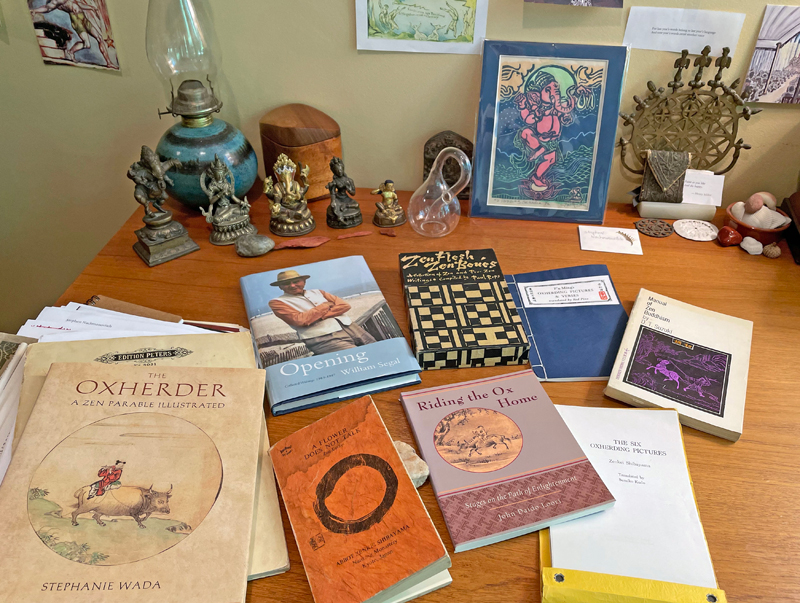

Stephen Nachmanovitch’s Desk.

Image: © Stephen Nachmanovitch

Within a few years, I discovered that I was an improvisational musician. The lines between composer, performer, doer, perceiver began to disappear. I loved the music of the past but what activated me was the music of the present, meaning music that is less than five minutes old. It seemed magical that I had a facility as an improviser that I could not approach playing pre-written compositions.

At the time of Gregory’s death at the San Francisco Zen Center, I found myself wanting to stick around and engage deeply in Zen practice with the people there. I found that Zen practice merged seamlessly with musical practice—sitting still in silence or moving and making sounds—music, dance, theatre, visual art, sitting still—all one practice. I also became fascinated with other traditions, Sufism, Pythagorean music-mysticism, Tibetan Buddhism. I met my wife in 1989 at the Kalachakra teachings of the Dalai Lama.

For the past 20 years and more, we have lived at the edge of a forest in central Virginia. I walk out here among the poplars and oaks, and the infinitely intertwined ecology of living beings. Now that I think of it in writing this to you, that theme of my mother’s surreptitious tree-kissing has been pervasive. In the 2020s, a good part of humanity is busy trying to build walls and barriers and arm themselves against the Other but another part of humanity is busy learning about mycelia and plant intelligence and the interdependence of all living creatures. During and since the pandemic, I’ve spent a lot of time in the forest hanging out with birds, recording and learning from them as a musician. The future—if we don’t destroy ourselves—is analogue. The future—if we don’t destroy ourselves—is one in which we begin to realize the interbeing of all organisms, the pattern that connects us all.

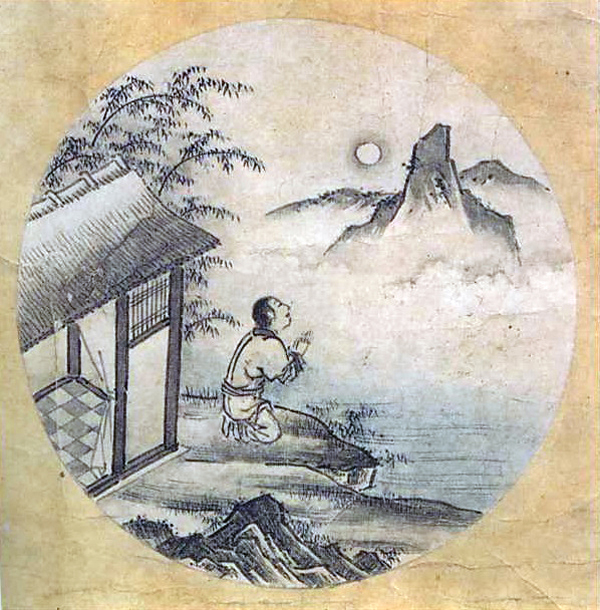

Alone in the wilderness, lost in the jungle, the boy is searching, searching!

The swelling waters, the far-away mountains, and the unending path;

Exhausted and in despair, he knows not where to go,

He only hears the evening cicadas singing in the maple-woods.

—Searching for the Ox

I encountered the oxherding pictures in the early 1970s. Steve Schoen, a psychiatrist in San Francisco whom I first met as a mutual friend of Gregory Bateson, gave me a xerox copy of a version of the pictures from Sung Dynasty China by Tzu-te Hui (or in Japanese, Jitoku), with commentary in the 1960s by Zenkei Shibayama, then abbot of the Nanzen-ji temple in Kyoto. This version has six pictures.

This is an old art form: symbolic instruction through a simple but open-ended picture book. In the West, we have the 21 arcana of the Tarot. Several of Blake’s illuminated printings were in this format: his early efforts, There is No Natural Religion, and All Religions Are One. Later the Gates of Paradise and finally his great Illustrations of the Book of Job. When Steve Schoen gave me those pictures I was working on my dissertation in Blake with Gregory Bateson, focused on Job. Over the 70s and 80s, studying Zen, I came across several other versions of the oxherding series. And now there are even more scattered on the desk as I write this to you today. [See Stephen’s desk above.]

By the stream and under the trees, scattered are the traces of the lost;

The sweet-scented grasses are growing thick—did he find the way?

However remote over the hills and far away the beast may wander,

His nose reaches the heavens and none can conceal it.

—Seeing the Traces

As a musician interested in visual music, I adopted what in the 70s was the latest technology: two Kodak slide projectors linked by a dissolve machine. I could program the dissolve machine with electronic bleeps on one track of a big four-track TEAC tape recorder, to create dissolves, quick cuts and other effects. That left two more tracks for stereo sound. So I could produce a multimedia composition with music and dissolving graphics that could be presented in public. The TEAC was especially unwieldy but did make a good stage prop. These were clunky, noisy, heavy machines (the two slide projectors had loud fans!). They had to be carted to a performance and laboriously set up with a screen or big white wall and loudspeakers, and the projectors adjusted to point at the exact same spot on the wall so the images would register with each other. But at the time this was really wonderful. And wouldn’t Blake have loved having something like that?

For the Taming the Mind Ox piece in 1984, I shot 35 mm slides of the ten Shubun pictures. I found in a Hollywood photography store some plastic slide mounts with circular rather than rectangular windows, so I could frame the circular pictures perfectly onscreen. I improvised the music onto the tape tracks with a five-string electric violin and various foot pedals. I premiered the piece, about ten minutes in length, at a concert of several of my visual music pieces at the UCLA music department in January of 1985, along with other pieces that were composed using a Fairlight video synthesizer.

On a yonder branch perches a nightingale cheerfully singing;

The sun is warm, and a soothing breeze blows, on the bank the willows are green;

The ox is there all by himself, nowhere is he to hide himself;

The splendid head decorated with stately horns what painter can reproduce him?

—Seeing the Ox

That was the last piece I created for the slide-tape medium. After that, I was doing visual music in video and then of course on the computer. In 2006, I recomposed the oxherding piece on the computer and created new music for it using violin and viola. I used the Shūbun pictures with the permission of the Shokoku-ji temple in Kyoto, though I believe they are now public domain.

In the video, I used dissolve effects by a small company called Pixelan. The violin and viola chase each other, like the boy and the ox, at first frenetically, then more slowly, then still, then open.

The pictures by Shūbun (15th century) are believed to be copies of a now-lost earlier set by Kakuan (12th century). Regarding all the old versions of the oxherding pictures, we know little or nothing of who these artists and poets were. “Very deep,” said Thomas Mann, “is the well of the past.” And even now, in the age of the internet and our mania for intellectual property, with all the thousands of quotes and citations tossed about, we know surprisingly little of who said what.

With the energy of his whole being, the boy has at last taken hold of the ox:

But how wild his will, how ungovernable his power!

At times he struts up a plateau,

When lo! he is lost again in a misty unpenetrable mountain-pass.

—Catching the Ox

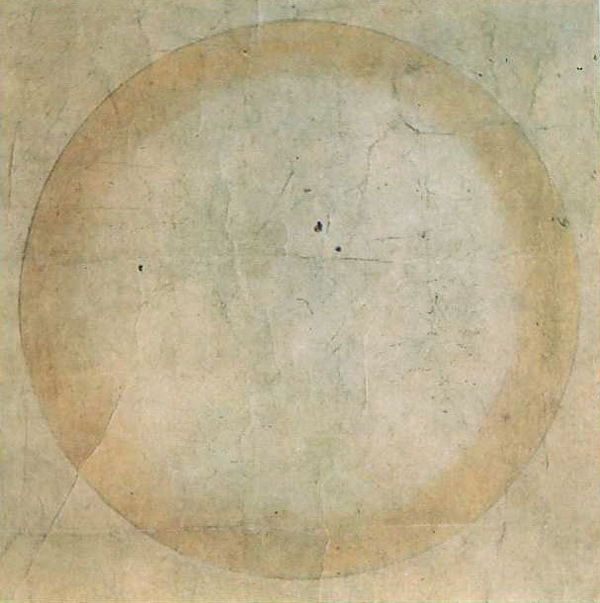

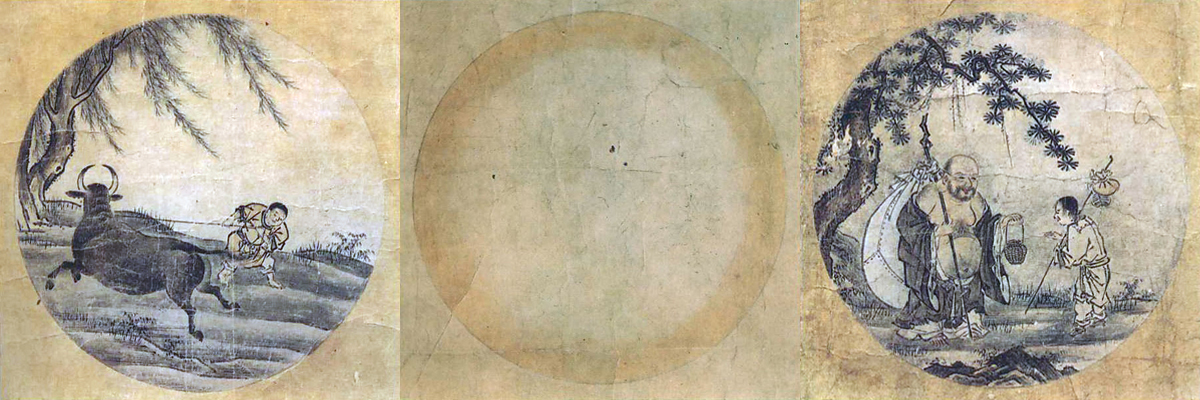

In the Jitoku version (the one with six pictures), #5 is the empty circle or enso and #6 is meeting the old man in the marketplace. Those are #8 and #10 respectively in the Shūbun and most of the other versions that have ten pictures. The final picture (absent in the P’u-Ming/Red Pine version) is very important. D.T. Suzuki titles it, “Entering the city with bliss-bestowing hands.”

Bill Segal, who really enjoyed being an old man, really went to town with that picture. Shibayama titles that final picture “Playing”. (I wonder now if that’s why Steve Schoen gave it to me?) In his comment on that picture, Shibayama tells the story of the little pigeon who sees a vast mountain range on fire and starts flying to a faraway lake to bring a few drops of water back to the mountain. He flies back and forth trying to put out the fire until he drops dead. This does not sound like “playing” but it strangely is—to engage in an act that clearly isn’t going to “work”, that won’t have any rewards but doing it for love nonetheless. In our current world which is on fire with broiling climate change and fascism, anything we can do to help will be minuscule in proportion to the situation. Yet to do it with love and actually with pleasure is perhaps a form of play.

The boy is not to separate himself with his whip and tether,

Lest the animal should wander away into a world of defilements;

When the ox is properly tended to, he will grow pure and docile;

Without a chain, nothing binding, he will by himself follow the oxherd.

—Herding the Ox

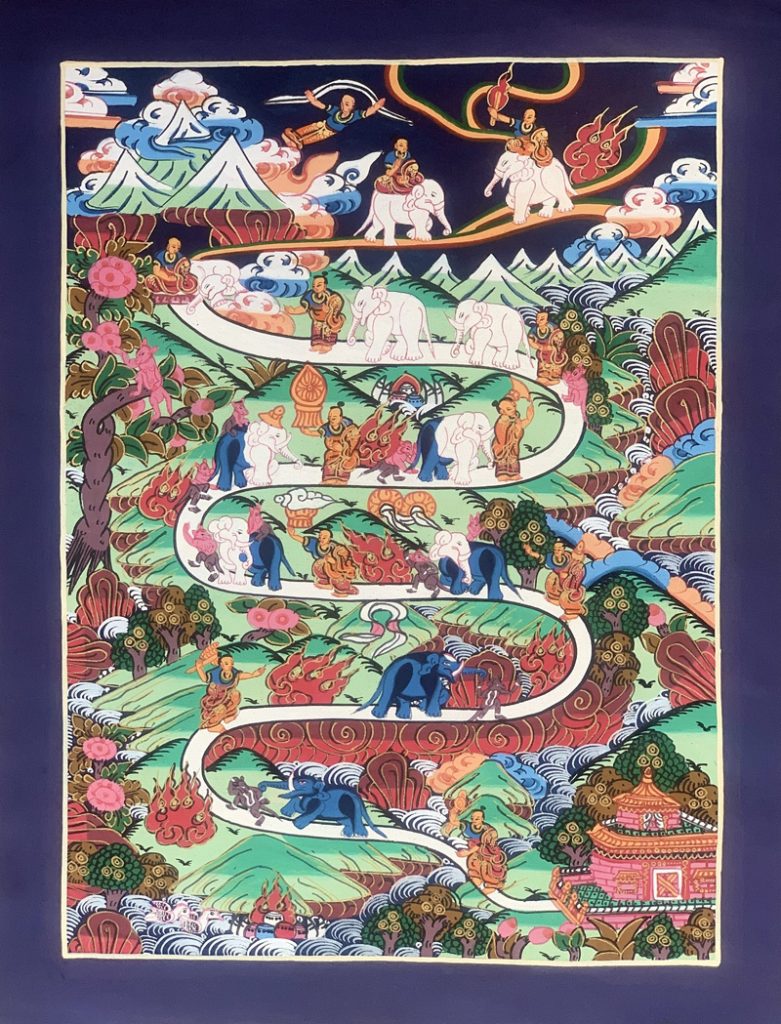

The oxherding tale is a picture book, a storybook, with little poems as captions to each of the ten pictures, depicting stages on the path of waking up. There are lots of these in different cultures, East and West. There are also Tibetan thangkas depicting ten or more steps to taming an elephant [see below].

The elephant is the unruly mind, and (like the ox) gradually changes colour from dark to light as the images progress. In real life, learning does not necessarily take place in stages. However, teachers and artists have often portrayed it as a sequence in order to simplify and condense. And because people like stories.

The many Chinese and Japanese versions of the oxherding pictures fall into two groups: those that end in the circle or enso that signifies realizing emptiness and the ones that go past the circle and end in the marketplace. This is a fundamental difference. Do you realize emptiness-vastness-clarity—which is a personal journey—and end there? Or do you take that realization (which is no longer just yours) and bring it into the marketplace—bring it to where others can get a taste of it as well?

Riding on the animal, he leisurely wends his way home:

Enveloped in the evening mist, how tunefully the flute vanishes away!

Singing a ditty, beating time, his heart is filled with a joy indescribable!

That he is now one of those who know, need it be told?

—Coming Home on the Ox’s Back

My personal preference is for the versions that end with the old man in the village. The versions that end in the enso evoke a beautiful state, but then what?

This is the sequence: you walk around not knowing there is a beast there at all, you see the beast, you chase the beast, you struggle with the beast, you tame the beast, and now you can ride on the beast’s back playing your music. Or perhaps the music that comes out of that flute is a different music—it’s no longer your music, it’s you and the beast together that are emitting that sound from the flute.

Now you bring the tame beast back to your pleasant place of peace. And then you disappear and realize the emptiness of inherent existence. Thus far the story aligns with those schools of Buddhism that are roughly called Hinayana. The aim if we want to call it that is for a person to attain enlightenment or awakening (nirvana, which means blowing out, as of a candle). Then you are in this fantastic place of meditative stillness and peace. I’m feeling that right now sitting on a stump in the forest—there’s suddenly a stillness within me, the forest is in focus.

Riding on the animal, he is at last back in his home,

Where lo! the ox is no more; the man alone sits serenely.

Though the red sun is high up in the sky, he is still quietly dreaming,

Under a straw-thatched roof are his whip and rope idly lying.

—The Ox Forgotten, Leaving the Man Alone

Today the forest with its dappled light feels Gerard Manley Hopkinsish. I’m so attracted to that tall thin poplar tree downhill to my left, it’s roughly northwest of my nose. It’s bathed in light, so beautiful and so quietening. The quietening of the heart, the quieting of the monkey-mind, the stubborn ox-mind.

The journey of the young person up to the empty frame is a solitary one. But then it opens out into a social context. In the versions of the oxherding pictures that don’t end in the circle, the boy comes out of the place of peace among the trees and sees the whole world of nature of which he is part.

You see a forest and it is all interactivity, it is all busy exchange and communication and mutual support and mutual eating. And then he comes into the village.

All is empty—the whip, the rope, the man, and the ox:

Who can ever survey the vastness of heaven?

Over the furnace burning ablaze, not a flake of snow can fall:

When this state of things obtains, manifest is the spirit of the ancient master.

—The Ox and the Man Both Gone out of Sight

The versions of the last oxherding picture again diverge. In the Shūbun version, it is the boy facing the grizzled, smiling, fat old man. The boy is carrying a small bag on the end of a stick over his shoulder. The old man is carrying a similar bag but it is enormous and full to bursting. So is the boy encountering a teacher or a role model? Is he encountering his future self? In the 1278 version from China or William Segal’s version of the ten pictures, there just is the old man and you might guess the boy may have spent years in his adventures between pictures #1–#9 and now it is he, as an old man, coming into the village with his big smile.

In the Suzuki translation, he comes to the village “with bliss-bestowing hands”. This old man is a teacher of bodhisattvas, someone passing on what he’s learned. He is giving it freely. He’s a beggar but also immensely wealthy with all that knowledge crammed into that bag. There’s something about the versions that end in this picture that says to me Mahayana Buddhism.

In Mahayana, maybe you’re a fortunate, skilled and devoted person who practises for years and attains some kind of enlightenment. But that’s nothing unless you use the enlightenment to help other sentient beings. And so we have the idea of the bodhisattva, the enlightening being, who refuses to get off the wheel of samsara until everyone else has gone first. That’s quite a job. You’d have to be willing to wait until Stalin, Trump and Putin live through innumerable lifetimes until they become enlightened, and go through the door before you.

To return to the Origin, to be back at the Source—already a false step this!

Far better it is to stay at home, blind and deaf, and without much ado;

Sitting in the hut, he takes no cognisance of things outside,

Behold the streams flowing—whither nobody knows; and the flowers vividly red—for whom are they?

—Returning to the Origin, Back to the Source

Entering the marketplace with bliss-bestowing hands. Buddhist insight is about waking up and the word buddha means a person who wakes up and helps other people to wake up.

The old man is reminiscent of Pu-Tai (Hotei in Japanese). Pu-Tai means “cloth sack”. He was a tenth-century Zen monk, fat, merry, eccentric. Early in the 20th century, Westerners often confused Pu-Tai or Bodai with the Buddha, just because of how the name sounded. Pu-Tai comes to mind as I look at a book of old Taoist poetry and prose by Lu Yu that I recently found: The Old Man Who Does As He Pleases.

I also have a single-picture version of the story, which was made for me in 2004 by an artist named Mark Fletcher. [See below.] It is one image: the boy tugging on the ox or rather both of them tugging against each other. Stubborn. It reminds me of Milton, a fairly small beagle belonging to my son, who could make himself weigh 200 pounds by angling his legs into the ground to stop you from pulling him in a direction in which he did not want to go. The boy and the beast are pulling in opposite directions, each with all his might. You have no idea who is going to “win”. But winning may not be the idea. You may say that the beast and the boy tame each other. And that pulling-against is the essence of life.

Bare-chested and bare-footed, he comes out into the market-place;

Daubed with mud and ashes, how broadly he smiles!

There is no need for the miraculous power of the gods,

For he touches, and lo! the dead trees are in full bloom.

—Entering the City with Bliss-bestowing Hands

In my video version, using the ten pictures attributed to Shūbun (15th century, with permission from the Shōkoku-ji temple in Kyoto) there are two voices tugging on each other and chasing each other around, violin and viola. Jittery and frenetic, then getting into sync, slowing down. Then there is just nature, the crooked tree. It ends with a duet of young person and old person. Is the old person the young one looking at his older self? Or is the old person the ox himself, bestowing bliss?

In the tradition, the beast is a purely rhetorical device, a metaphor. Such a metaphor of training an ox or bull or buffalo or elephant means one thing if you’re thinking of you, the person, the ego, the mind, learning self-discipline—the beast being all your recalcitrant stubborn or addictive tendencies. But in this phase of my life, I’m also interested in interspecies communication. Part of the enlightenment that is possible in our age, despite all the greed, hate and delusion that besets our nations, is that we now realize at a scientific level that species are talking to each other. There is no “higher” species mind-taming a “lower” one. We’re all in this music of communication together.

Finally, I can’t leave the topic of taming the mind-ox without mentioning Saint-Exupery’s theme of apprivoiser in The Little Prince. Apprivoiser means to tame but with overtones of you and the animal becoming each other’s familiars. Making it your own but equally making you its own. Taking care of a living being. In the act of caretaking, self and other, at least for a while, are not different.

Tibetan Steps to Tame an Elephant.

Image: Public Domain

Post Notes

- Feature image: Tenshō Shūbun, Oxherding Pictures, #4, #8 & #10, Public Domain

- Stephen Nachmanovitch’s website

- Stephen Nachmanovitch, Being Whole

- Stephen Nachmanovitch: The Art of Is

- Stephen Nachmanovitch: Free Play

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Eric Nicholson: William Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme