Thinking Allowed, Rollo May talking with Jeffrey Mishlove

A personal story of redemption

“Withdraw into yourself and look.

And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet,

act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful:

he cuts away here, he smoothes there,

he makes this line lighter, this other purer,

until a lovely face has grown upon his work.

So do you also:

cut away all that is excessive,

straighten all that is crooked,

bring light to all that is overcast,

labour to make all one glow of beauty

and never cease chiselling your statue,

until there shall shine out on you from it

the godlike splendour of virtue,

until you shall see the perfect goodness

surely established in the stainless shrine.”

—Plotinus, “The Enneads”

ROLLO REESE MAY (21st April 1909–22nd October 1994) was a highly respected American existential psychotherapist, best known for his work on anxiety and the awareness of death. Drawing on the philosophical works of Jean-Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger and Søren Kierkegaard, May believed that anxiety, rather than being a symptom to be removed from the psyche, is, in fact, a gateway to an exploration into the meaning of one’s very own self. He also believed that anxiety was an opportunity for creativity and a stimulus toward taking action and being courageous; in short, understanding what it means to be human.

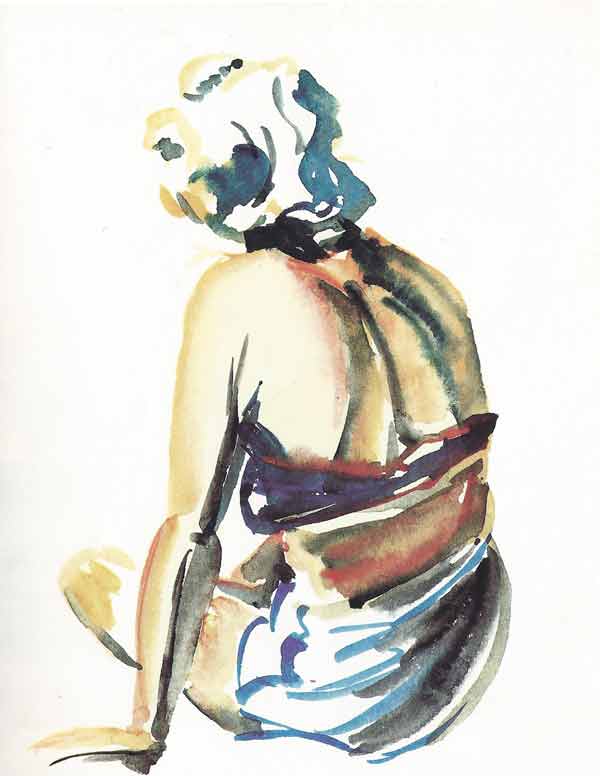

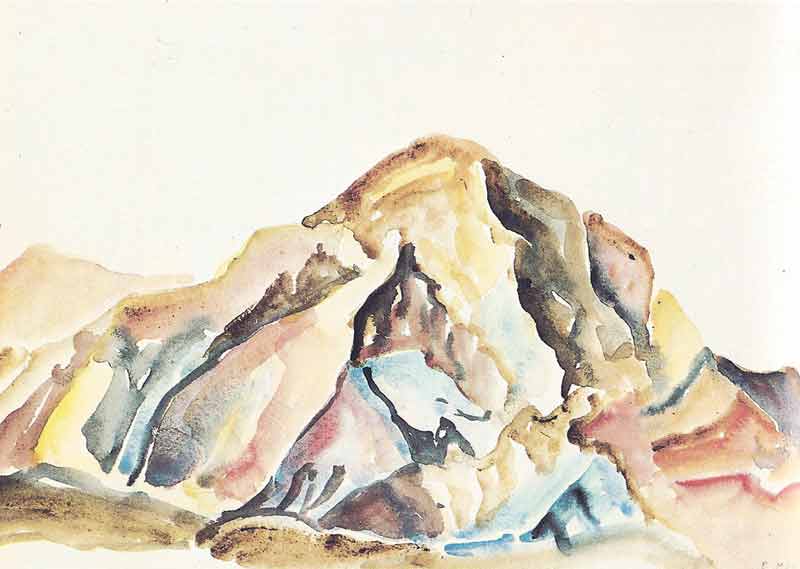

Rollo May wrote many seminal books—The Meaning of Anxiety, Love and Will, The Courage to Create, Freedom and Destiny—and yet it is his lesser-known memoir/travelogue, My Quest for Beauty, which captivates me the most. Illustrated with his own paintings and pencil drawings, he recounts his earliest memories as a young man of 21 years, teaching English at Anatolia College in Saloniki, Greece, which formed a pivotal moment on his psychological path:

Finally, in the spring of that second year I had what is called, euphemistically, a nervous breakdown. Which meant simply that the rules, principles, values by which I used to work and live simply did not suffice anymore. I got so completely fatigued that I had to go to bed for two weeks to get enough energy to continue my teaching. I had learned enough psychology at college to know that these symptoms meant that something was wrong with my whole way of life. I had to find some new goals and purposes for my living and to relinquish my moralistic, somewhat rigid way of existence. In the United States nowadays I would have gone to a therapist. But then, in 1931, I was in a psychologically primitive culture where only a few people spoke my language. What to do?

Photograph: © Rollo May

He takes off to reflect upon his predicament, wandering atop Mount Hortiati in all weathers, trying to find at least some form of relief from his mental anguish. And then it happens:

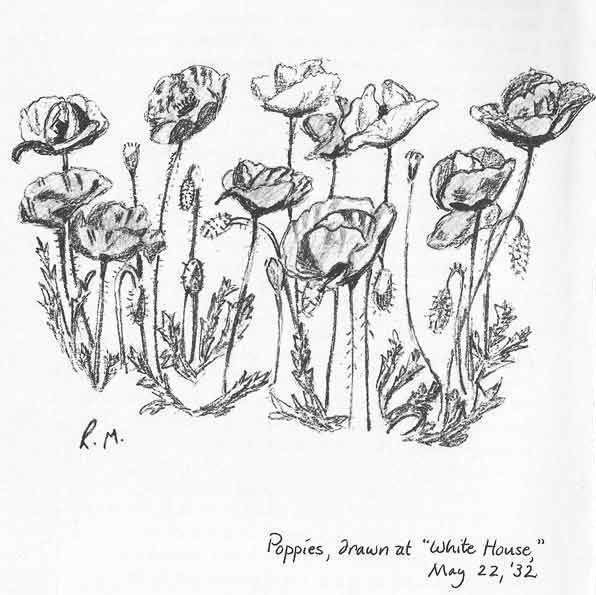

After two days and two nights I started back down the mountain again. I had a few more days to spend with my friends before going back to teaching and during this time I walked mostly around the surrounding hills. Ascending one hill I found myself suddenly knee deep in a field of wild poppies covering the whole hillside. It was a gorgeous sight: brilliantly crimson and scarlet, the poppies were lovely forms as they bent delicately in one direction and then another. Their perfect movements together seemed like children in a ballet, perhaps the Nutcracker Suite at Christmas time. I stood there, intoxicated, wholly captivated by this sight. Wordsworth’s words came into my mind:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils …Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.My poppies in their dance were swaying in unison and bowing in the slight breeze, each of them having a miraculous perfection of beauty in itself. When they nodded toward me they presented their yellow-black centres, and when they nodded away, they then seemed a fiery scarlet …

I realized that I had not listened to my inner voice, which had tried to talk to me about beauty. I had been too hard-working, too “principled” to spend time merely looking at flowers! It seems it had taken a collapse of my whole former way of life for this voice to make itself heard. This inner voice hereafter would always be redolent with the slight perfume that covered the hillside that morning.

Photograph: © Rollo May

As the title of his book suggests, Rollo May attempts to understand the meaning and purpose of beauty, finding inspiration and guidance in his travels throughout Europe, his psychotherapeutic practice with his patients and his love of the cultural arts:

What is Beauty?

Beauty is the experience that gives us a sense of joy and a sense of peace simultaneously. Other happenings give us joy and afterwards a peace but in beauty these are the same experience. Beauty is serene and at the same time exhilarating; it increases one’s sense of being alive. Beauty not only gives us a feeling of wonder; it imparts to us at the same moment a timelessness, a repose—which is why we speak of beauty as being eternal.Beauty is the mystery that enchants us. Like all higher experiences of being human, beauty is dynamic; its sense of repose, paradoxically, is never dead and if it seems to be dead, it is no longer beauty …

This is why, when we are before an image of beauty, we instinctively remain silent. We look and we listen. When we talk too much about beauty, we are objectifying it, putting it outside ourselves, destroying the inner visions and reducing it to objective chatter. We must preserve the capacity for wonder—which is the awareness that we can never fully explain the inner experience of beauty.

Photograph: © Rollo May

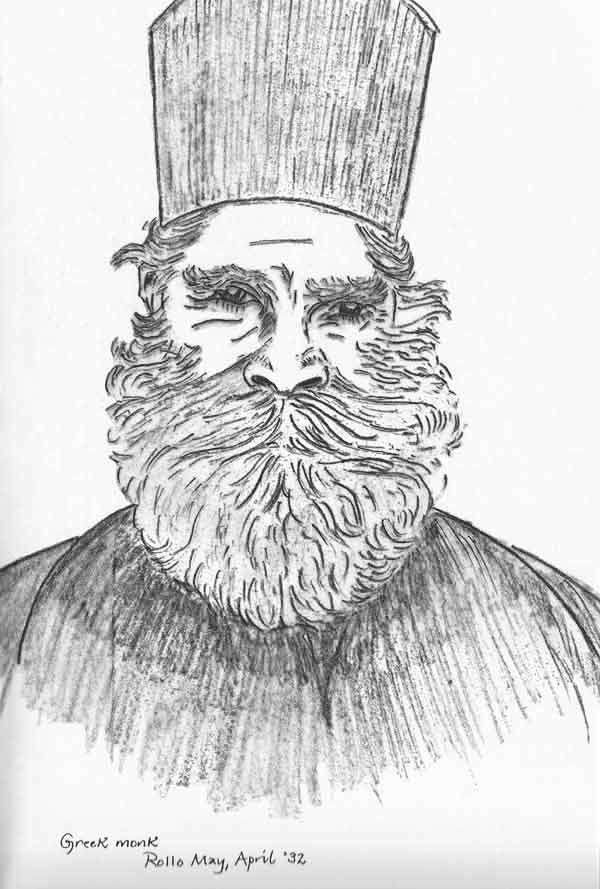

Sojourning in the Hellenic continent, it is a week before Easter, and Rollo May and three other travelling companions embark upon a trip to the holy mountain of Mount Athos, a thirty-mile-long peninsula separated from the mainland and capital to all the monasteries of the Greek Orthodox Church (and where women have been forbidden to visit since the eleventh century). After his experience of oneness with the poppy field, Rollo May is keen to go ever deeper into the meaning of things:

It was, so I had heard, a land where silence and serenity were an essential part of its beauty. I sought neither the wisdom of men nor conversation with the monks. I wanted to be quiet with my own heart and open to my own spirit. I sought especially the answer to the question of the relationship of the beauty of nature to the Infinite, to what some people call the Absolute and others call God. It was thus a strange kind of expectancy that I felt as I sat with my companions on the ship’s deck looking at the stars gleaming in the endless black void of nothingness.

They visit sketes and monasteries, tasting their basic fare and lying in their springless beds. And yet, May is not particularly interested in understanding the monks’ way of life: it is nature he has come to behold in all her glory and the manifestation and meaning of beauty. He starts to reflect on the “sensitive persons, especially writers, who have gone to Athos as modern-day pilgrims to awaken their hearts, to re-kindle some inner spiritual reality”:

A surprising number of authors have gone to restore their souls in the silence and serenity to be found at Athos. The modern Greek novelist, Nikos Kazantzakis [author of Zorba the Greek], when a young man, had come there with a companion some twenty years after we were here. He had been seething with spiritual confusion.

‘I did not know what I was going to do with my life,’ so writes Kazantzakis. ‘Before anything I wanted to find an answer, my answer, to the timeless questions …’

In the course of his walks, Kazantzakis had long talks with monks … and with hermits in caves on the cliffs over the Aegean Sea.

He tells how he confessed to one Holy Man his inner struggles. The Ascetic answered, ‘Woe is you, woe is you, unfortunate boy. You shall be devoured by the mind; you shall be devoured by the ego—the “me”, the self.’

Kazantzakis took his leave with the statement, ‘Tell God it is not our fault but His—because he made the world so beautiful.”

As Kazantzakis and his companion left Athos, he pointed to an almond tree in bloom, and cried, ‘Angelos, during the whole of this pilgrimage our hearts have been tormented by many intricate questions. Now, behold the answer!’

And his friend, in answer, recited the little poem:

I said to the almond tree,

Sister, speak to me of God.

And the almond tree blossomed.

The time spent on Mount Athos leaves Rollo May deeply transformed. His intimate glimpse of the Infinite has precipitated an inner shift and he returns to the States with an invigorated perspective on life, albeit with questions still burning in his heart:

Beauty is not God but it is the resplendent gown of God and of our spiritual life. Such a thought grasped Keats, who wrote:

Beauty is truth, truth beauty—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.Yes. But there were still things I yearned to know. Is beauty at least our pathway to the spirit? Is beauty the gateway to spiritual enchantment and to the serenity of eternity? Is beauty related to the eternity of death?

Photograph: © Rollo May

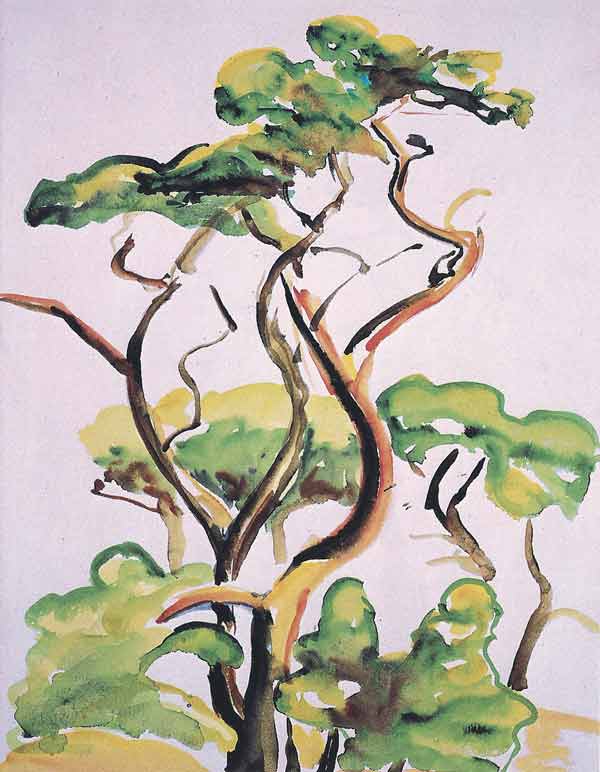

Rollo May carved out his career in the field of existential psychotherapy; however, he continued to explore the visual arts throughout his life, documenting his travels across continents through the medium of painting and drawing in search of his Beautiful muse and her relationship to the meaning of life. A whole chapter is devoted to colour plates of his accomplished pastels and watercolours:

They began with that historic drawing of poppies which meant so much because it was the opening of new worlds to me.

Painting is not something done chiefly with a brush and some colours. It is, rather, a way of seeing the world … One’s actual painting is done inside one’s imagination and it is a function of how the individual relates to the world. The threadbare story of the blind men feeling the elephant and saying it is like a rope, a piece of leather, a rug and so on, is true on a more profound level. Each of us sees the world as an individual, alone, caught up in a vast maelstrom; but by our culture, we learn to communicate with our fellow human beings. Poetry, dancing, painting and other arts are all ways of communciating. The philosopher Kant said we not only see the world but the world conforms to our way of seeing it. This is certainly true in the field of art.

The contribution of art is that, in our threescore and ten years on this planet, we are enabled to share, to give to each other, to communicate, to love the world and, in the broad sense, to love each other. This will sound strange to those who think the world is a cold mass of whirling star dust but not to those who can form their world in communication by whatever beauty they can see and experience.

The anxiety in creating—which we see most clearly in persons like Alberto Giacometti [Swiss Surrealist sculptor] or Michelangelo or Beethoven—is overcome by playing … this playing (which may also be hard work) is our human way of overcoming the dualism—finite and infinite—in producing a work of art. The art unites both of these. The world becomes lonely no more, for one experiences being an integral part of it.

Photograph: © Rollo May

Possibly my most favourite chapter in this exquisite journal of self-discovery concerns Rollo May’s critique of the human mind and the process it undergoes in the creative act, arguing that “the ability to create is essentially the ability to find form in chaos, to create form where there is only formlessness”:

Beauty reveals a form in the universe—the harmony of the spheres, as Kepler called it. It is a form which is the circling of the planets. It is a form which is felt in the curves and balance of our own bodies. And it is present especially in the way we see the world, for we form the world in the very act of perceiving it. The imagination to do this is one of the elements that makes us human beings.

Interestingly, Rollo May was a practitioner of transcendental meditation and found the technique to be beneficial in the treatment of anxiety; nevertheless, such was its calming effects on the mind, it had disastrous consequences for his artistic work:

There is a danger in erasing chaos too easily, for it then takes away one’s stimulation. Several years ago, I took the training for transcendental meditation. I have always been interesting in meditating and have done it more or less on my own. When I finished that course and my mantra was given to me, I was instructed to meditate twenty minutes in the morning as soon as I woke up and twenty minutes at four or five o’clock in the afternoon. So I, being an obedient soul, started out doing that. I found that after meditating I would go to my desk in my studio and sit there to write. And nothing would come. Everything was so peaceful, so harmonious; I was blissed out. And I had to realize through harsh experience that the secret of being a writer is to go to your desk with your mind full of chaos, full of formlessness—formlessness of the night before, formlessness which threatens you, changes you.

The essence of a writer is that out of this chaos, through struggle or joy or grief—through trying a dozen or perhaps a hundred ways in rewriting—one finally get’s one’s ideas into some kind of form. So I learned I had to meditate with discretion in the early morning in order not to lose the chaos and to choose those times when I had finished the day’s work and was ready to be blissed out with pleasure.

Photograph: © Rollo May

Haunted by his alpine travels, Rollo May revisits Europe some years later, this time on a road trip through the foothills of the French Alps toward Chamonix and Mount Blanc. Again, he is filled with awe and wonder at the magnificent landscapes lain out before him and the profound feelings they evoke:

We arrived in Chamonix after dark. Our room in the inn had a large picture window to the southeast and in the darkness we could see the vast dark lines of Mount Blanc, silent lord of the entire horizon. On the windowsill of the room was the customary box of geraniums, which made a foreground over which we could feel and dimly see the presence of the great mountain.

The next morning, I sat on the windowsill for half an hour intensely concentrating on the mountain peak. I cleared my mind of everything and held my gaze steadily on the great cone of glowing snow. As I gazed for the first part of the half hour, Mount Blanc remained a realistic mountain, pure ivory white, incredibly beautiful against the deep blue of the morning sky.

Then, as I continued to concentrate on it, the mountain gradually changed before my eyes into another form. It became abstract. It was now, as the underlying form emerged, composed of disembodied squares and circles and planes. I loved it still, as I love cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque in the first decade of this century. The mountain form seemed to be painted on a canvas, it was disembodied, pure form with no weight or movement. Or one could easily say, the mountain form was all weight and all movement; with living form it does not matter …

But as I continued to concentrate steadily on it, this weightless form gradually changed again. The vast mountain took on a body, now organic, three-dimensional. It became a new being on a new level. Now I saw it in a living depth. The glowing ivory forms had come together again into an organism, not personal but neither was it impersonal. It seemed to be pure form. I felt more than saw an embodied structure, now an ultimate form, part of the universe as I was also. The mountain, like myself looking at it, embodied a universe of beauty and meaning …

This experience of living forms, this embodied being, took me out of myself. Whenever I called it out of the past and into my mind again, it gave me a new experience which was beyond living or dying. The feeling was oceanic, as Freud of Einstein would say; it was my participation in the Being of the universe.

Such an experience cannot be said to exist only in my imagination, nor is it solely a knd of ‘telepathy’ emerging from Mount Blanc. The experience is both inner and outer, both subjective and objective. It is a fusion of my imagination and the emanating form of the mountain.

Undoubtedly, the Zen master, Qingyuan Weixin’s words come to mind (translated by D.T. Suzuki): “Before a man studies Zen, to him mountains are mountains and waters are waters; after he gets an insight into the truth of Zen through the instruction of a good master, mountains to him are not mountains and waters are not waters; but after this when he really attains to the abode of rest, mountains are once more mountains and waters are waters.”

Photograph: © Rollo May

My Quest for Beauty belongs to that rare category of literature that combines both the search for universal truth with deeply personal reminiscence—Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, Jack Kerouac’s Alone on a Mountaintop and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Meditations of a Solitary Walker immediately come to mind as similarly inspiring literary gems.

Moreover, Rollo May’s reflections on the power and mystery of art and the creative process is itself a work of beauty, lifting us up out of the mire of daily existence, elevating our minds and nourishing our souls:

Beauty is the form which reaches most deeply into the human heart … It is the language which translates all the moods of humanity into feelings and insights and sensual experience that we can understand. In beauty there are no foreigners: the deeper we penetrate into the human soul, be it of ourselves or our neighbours, the more we find ourselves at one with people of all nations … It is by beauty that we feel the pulse of all mankind.

Post Notes

- Rashid Maxwell: To Save the Planet With a Paintbrush

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Paul Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue

- Rupert Spira: A Meditation on I Am