Image: Public Domain

To write is to live

and to live is to write

“When a truly great and unique spirit speaks,

the lesser ones must be silent.”

—Franz Xaver Kappus

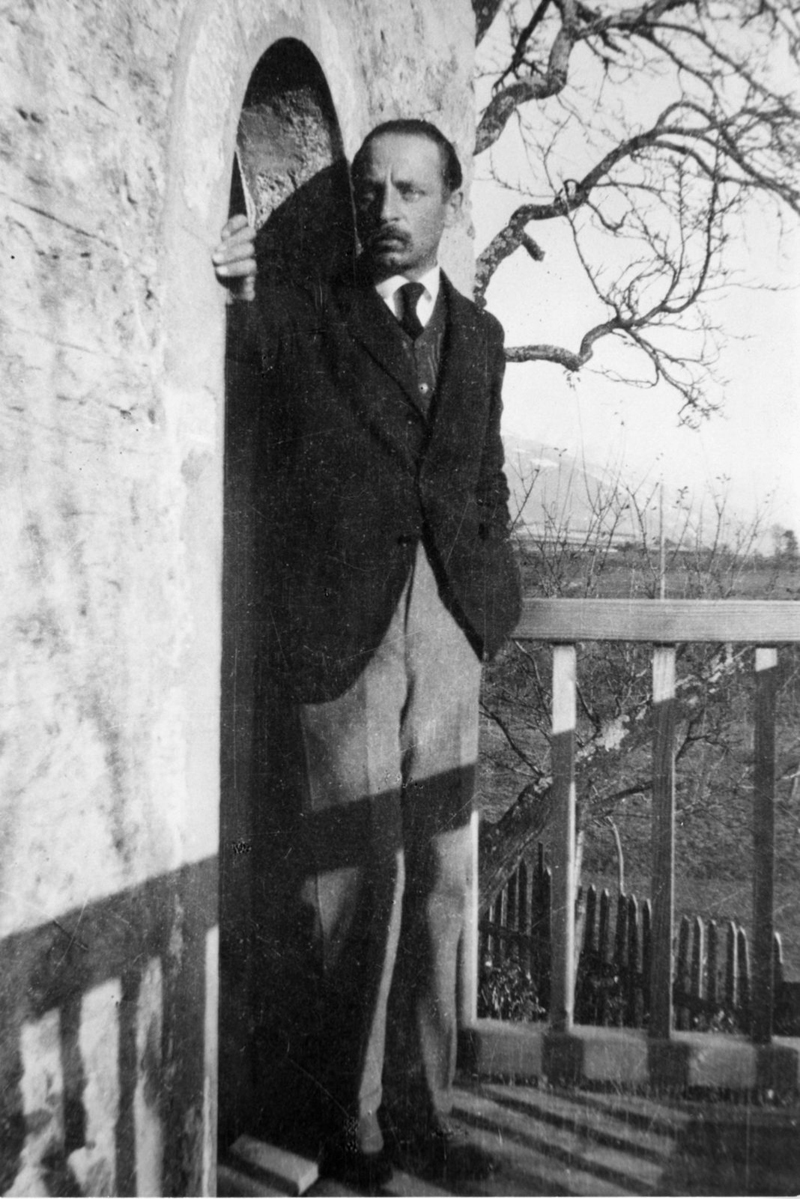

AT THE TURN of the last century, a 19-year-old student at the Military Academy of Vienna, named Franz Xaver Kappus, wanted career advice on his impending secondment to the armed forces, as well as a literary critique on a handful of poems he had recently composed. He decided to send them to an alumnus of the academy, the Austrian poet, Rainer Maria Rilke.

Rilke (4th December 1875–29th December 1926) was one of the most significant poets in the German language. Drawing on the contemporaneous theories of Sigmund Freud, his work often focuses on an individual’s yearning for communion with the innermost self, written at a time when mankind was plagued with nihilistic and chaotic interpretations of the world.

And thus, his correspondence with Kappus, one that lasted between 1902 and 1908, would crystallize Rilke’s aesthetic and philosophical sensibilities over the course of ten letters, with advice ranging from loneliness, sexuality, Nature and the need to trust one’s own inner judgement.

Three years after Rilke’s death, Kappus assembled and published the letters titled, Letters to a Young Poet (Briefe an einen jungen Dichter) in 1929.

Look to your own self for guidance

In the first letter, rather than offer any critique of Kappus’ poetry, Rilke immediately encourages his young correspondent to abandon all need for outside validation of his work and, instead, to look unto his own self for guidance:

There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer.

And if this answer rings out in assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple ‘I must’, then build your life in accordance with this necessity; your whole life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse.

—Letter 1

Moreover, it is only by tapping into the innermost recesses of oneself that the calling to the way of the artist can be discovered:

So, dear Sir, I can’t give you any advice but this: to go into yourself and see how deep the place is from which your life flows; at its source you will find the answer to the question of whether you must create. Accept that answer, just as it is given to you, without trying to interpret it. Perhaps you will discover that you are called to be an artist.

Then take that destiny upon yourself and bear it, its burden and its greatness, without ever asking what reward might come from outside. For the creator must be a world for himself and must find everything in himself and in Nature, to whom his whole life is devoted.

—Letter 1

Image: Public Domain

Great art takes time

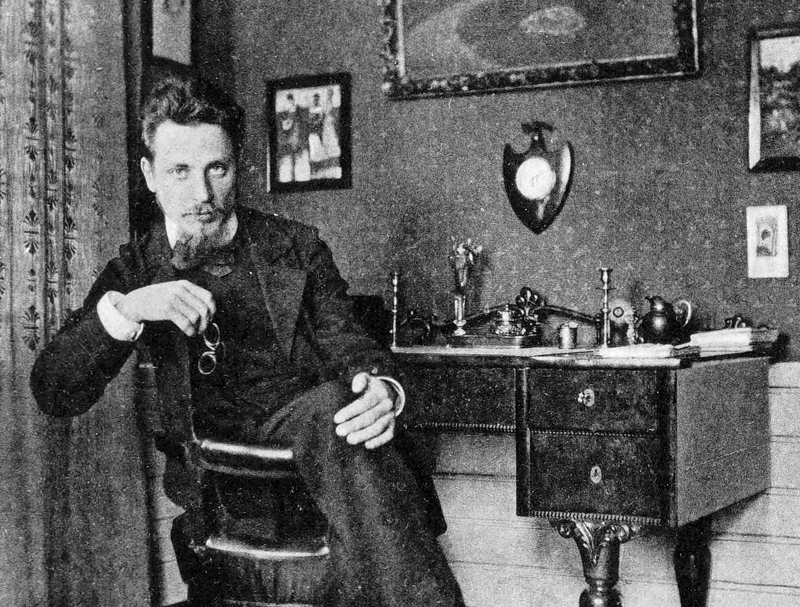

For Rilke, nourishing the impulse to create a unique artistic vision, however, cannot be forced:

Allow your judgements their own silent, undisturbed development, which, like all progress, must come from deep within and cannot be forced or hastened. Everything is gestation and then birthing.

To let each impression and each embryo of a feeling come to completion, entirely in itself, in the dark, in the unsayable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of one’s own understanding, and with deep humility and patience to wait for the hour when a new clarity is born: this alone is what it means to live as an artist: in understanding as in creating.

—Letter 3

Rilke compares the unfolding life of an artist to that of a tree, patiently withstanding hardship:

In this there is no measuring with time, a year doesn’t matter and ten years are nothing. Being an artist means: not numbering and counting but ripening like a tree, which doesn’t force its sap and stands confidently in the storms of spring, not afraid that afterward summer may not come.

It does come. But it comes only to those who are patient, who are there as if eternity lay before them, so unconcernedly silent and vast. I learn it every day of my life, learn it with pain I am grateful for: patience is everything!

—Letter 3

Moreover, it is Nature that inspires and unleashes within the artist a sense of awe and wonderment:

If you trust in Nature, in what is simple in Nature, in the small things that hardly anyone sees and that can so suddenly become huge, immeasurable; if you have this love for what is humble and try very simply, as someone who serves, to win the confidence of what seems poor: then everything will become easier for you, more coherent and somehow more reconciling, not in your conscious mind perhaps, which stays behind, astonished, but in your innermost awareness, awakeness and knowledge.

—Letter 4

Love is all you need

Contained within the correspondence, Rilke also discusses affairs of the heart and the nature of love; rather than being something co-dependent and stifling, it is to be celebrated as an inspiration to greatness:

It is also good to love: because love is difficult. For one human being to love another human being: that is perhaps the most difficult task that has been entrusted to us, the ultimate task, the final test and proof, the work for which all other work is merely preparation.

Loving does not at first mean merging, surrendering and uniting with another person (for what would a union be of two people who are unclarified, unfinished and still incoherent?), it is a high inducement for the individual to ripen, to become something in himself, to become world, to become world in himself for the sake of another person; it is a great, demanding claim on him, something that chooses him and calls him to vast distances.

—Letter 7

Image: Public Domain

In silence we find ourselves

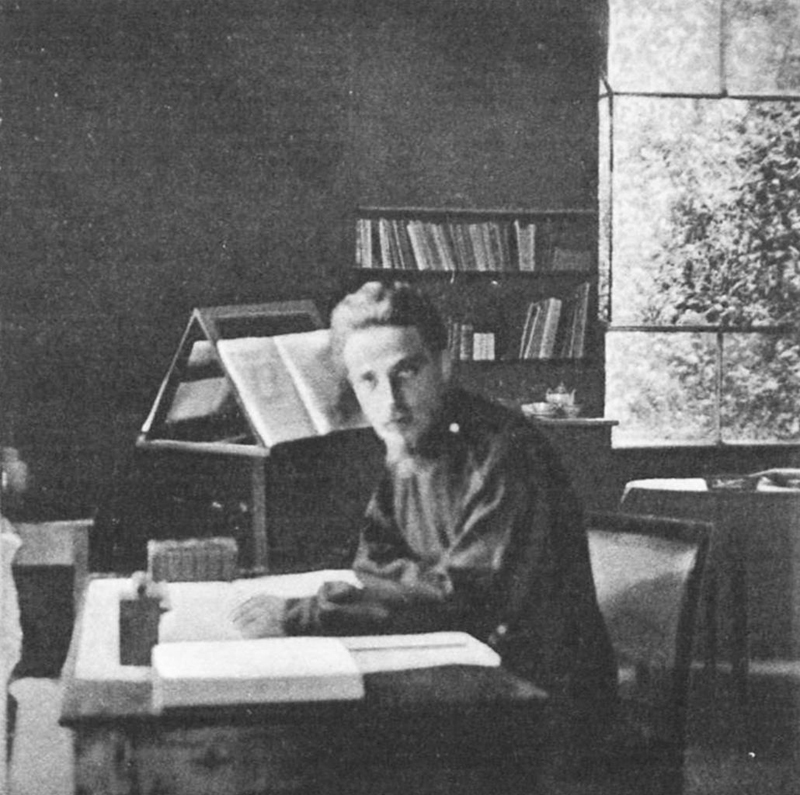

In his final letters, Rilke returns to the theme of mankind’s place in the cosmos and that, at the end of the day, we are all ultimately alone. And yet, possessed of such understanding, we can in fact discover infinite possibilities within ourselves and in relationship with others:

We are solitary. We can delude ourselves about this and act as if it were not true. That is all. But how much better it is to recognize that we are alone; yes, even to begin from this realization. It will, of course, make us dizzy; for all points that our eyes used to rest on are taken away from us, there is no longer anything near us and everything far away is infinitely far.

A man taken out of his room and, almost without preparation or transition, placed on the heights of a great mountain range, would feel something like that: an unequalled insecurity, an abandonment to the nameless, would almost annihilate him.

He would feel he was falling or think he was being catapulted out into space or exploded into a thousand pieces: what a colossal lie his brain would have to invent in order to catch up with and explain the situation of his senses.

That is how all distances, all measures, change for the person who becomes solitary; many of these changes occur suddenly and then, as with the man on the mountaintop, unusual fantasies and strange feelings arise, which seem to grow out beyond all that is bearable. But it is necessary for us to experience that too. We must accept our reality as vastly as we possibly can; everything, even the unprecedented, must be possible within it.

This is in the end the only kind of courage that is required of us: the courage to face the strangest, most unusual, most inexplicable experiences that can meet us. The fact that people have in this sense been cowardly has done infinite harm to life; the experiences that are called apparitions, the whole so-called ‘spirit world’, death, all these things that are so closely related to us, have through our daily defensiveness been so entirely pushed out of life that the senses with which we might have been able to grasp them have atrophied. To say nothing of God.

But the fear of the inexplicable has not only impoverished the reality of the individual; it has also narrowed the relationship between one human being and another, which has as it were been lifted out of the riverbed of infinite possibilities and set down in a fallow place on the bank, where nothing happens.

For it is not only indolence that causes human relationships to be repeated from case to case with such unspeakable monotony and boredom; it is timidity before any new, inconceivable experience, which we don’t think we can deal with.

But only someone who is ready for everything, who doesn’t exclude any experience, even the most incomprehensible, will live the relationship with another person as something alive and will himself sound the depths of his own being.

—Letter 8

Image: Public Domain

In his final letter, Rilke reiterates his counsel for the need for introspection and implores Kappus to delve deep into his innermost being in order to touch the omniscient stillness of life itself:

It must be immense, this silence, in which sounds and movements have room and if one thinks that along with all this the presence of the distant sea also resounds, perhaps as the innermost note in this prehistoric harmony, then one can only wish that you are trustingly and patiently letting the magnificent solitude work upon you, this solitude which can no longer be erased from your life; which, in everything that is in store for you to experience and to do, will act an anonymous influence, continuously and gently decisive, rather as the blood of our ancestors incessantly moves in us and combines with our own to form the unique, unrepeatable being that we are at every turning of our life.

—Letter 10

Introducing a new translation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet

by Ulrich Baer from Warbler Press: