How the power of solitude inspired a poetic genius

I remember how my life’s work developed from the time when I was very young. When I was about 25 years I used to live in utmost seclusion in the solitude of an obscure Bengal village by the river Ganges in a boat house.

The wild ducks which came during the time of autumn from the Himalayan lakes were my only living companions, and in the solitude I seem to have drunk in the open space like wine overflowing with sunshine, and the murmur of the river used to speak to me and tell me the secrets of nature …

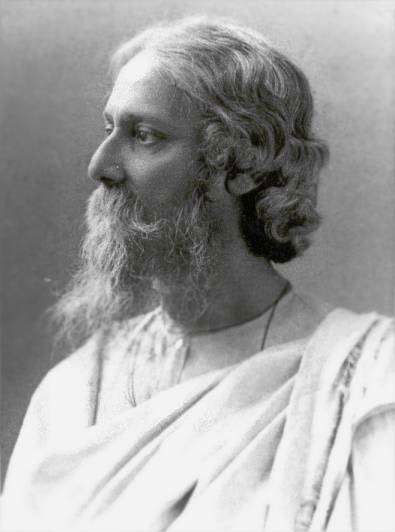

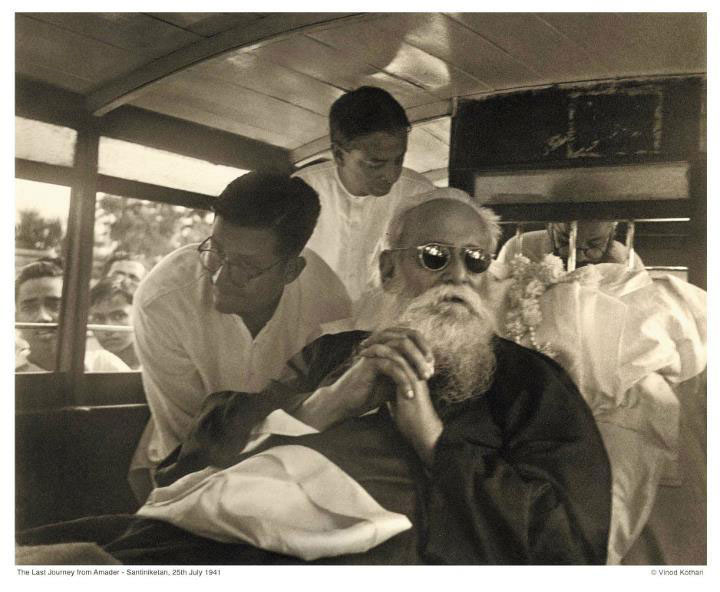

THERE ISN’T A single artistic discipline that Bengali polymath, Rabindranath Tagore (7th May 1861–7th August 1941), hasn’t graced with his exemplary talent—literature, philosophy, drama, music, art. It is poetry, however, for which Tagore is best known, having composed some of the most exquisite, lyrical and naturalistic verse ever to be published, garnering him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

And I passed my days in the solitude dreaming and giving shape to my dream in poems and studies and sending out my thoughts to the Calcutta public through the magazines and other papers. You can well understand that it was a life quite different from the life of the West.

I do not know if any of your Western poets or writers do pass the greatest part of their young days in such absolute seclusion. I am almost certain that it cannot be possible and that seclusion itself has no place in the Western world …

The pristine stillness of his surroundings enabled Tagore to plummet the deepest depths of his creativity and develop a unique poetic identity. Rejecting more conventional linguistic models based on classical Sanskrit, he was able to modernize Bengali literature by articulating himself through more radical forms of literary expression, with subject matter as diverse as spirituality, politics and the natural world.

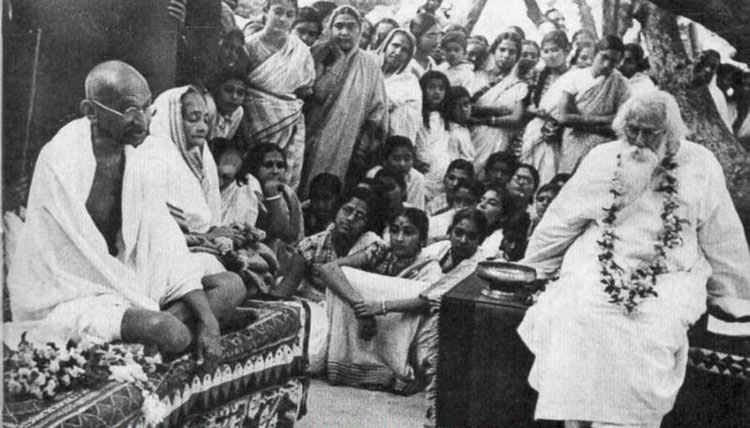

at Shantiniketan, British India (1940).

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

And my life went on like this. I was an obscure individual—to most of my country men in those days. I mean that my name was hardly known outside my own province, but I was quite content with that obscurity, which protected me from the curiosity of the crowds.

And then came a time when my heart felt a longing to come out of that solitude and to do some work for my fellow human being and not merely give shapes to my dreams and meditate deeply on the problems of life, but try to give expression to my ideas through some definite work, some definitive service for my fellow beings …

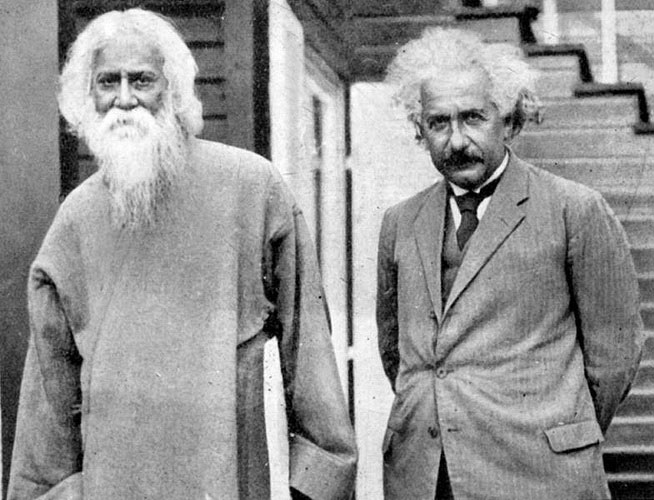

Having been isolated from the world for so many years, the crescendoing poetic pulse within Tagore’s breast pushed him out onto the literary, and political, stage, fostering a renaissance of Indian thought and culture. He travelled widely across five continents and was friends with many notable 20th-century figures, namely Henri Bergson, William Butler Yeats, H.G. Wells, Robert Frost, Ezra Pound, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi and Albert Einstein. And yet, a project in Bengal would remain the closest to his heart.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

And the one thing, the one work which came to my mind was to teach children. It was not because I was specially fitted for this work of teaching, for I have not had myself the full benefit of a regular education. For some time I hesitated to take upon myself this task, but I felt that as I had a deep love for nature I had naturally love for children also.

My object in starting this institution was to give the children of men full freedom of joy, of life and of communion with nature. I myself had suffered when I was young through the impediments which were inflicted upon most boys while they attended school and I have had to go through the machine of education which crushed the joy and freedom of life for which children have such insatiable thirst. And my object was to give freedom and joy to children of men …

In 1921, Tagore established the Visva Bharati, located in Santiniketan, West Bengal—an academic institution devoted to the education of the young in the pursuit of “freedom and joy”, funded by his Swedish Academy award. A regular mentor and teacher, he devoted much of his life imparting his humanitarian vision of the power of enlightened tuition.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

And so I had a few boys around me, and I taught them, and I tried to make them happy. I was their playmate. I was their companion. I shared their life, and I felt that I was the biggest child of the party. And we all grew up together in this atmosphere of freedom. The vigour and the joy of the children, their chats and songs filled the air with a spirit of delight, which I drank every day I was there.

And in the evening during the sunset hour I often used to sit alone watching the trees of the shadowing avenue, and in the silence of the afternoon I could hear distinctly the voices of the children coming up in the air, and it seemed to me that these shouts and songs and glad voices were like those trees, which come out from the heart of the earth like fountains of life towards the bosom of the infinite sky …

Tagore championed the rights of the individual; he abhorred any form of oppression and was a staunch defender of Indian nationalism. He believed that self-knowledge and education set people free, especially when they were taught in an atmosphere with a strong emphasis on personal liberty. Only then could they find inner peace and harmony, leading into communion with the whole of mankind.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

And it symbolized, it brought before my mind the whole cry of human life, all expressions of joy and aspirations of men rising from the heart of Humanity up to this sky. I could see that, and I knew that we also, the grown-up children, send up our cries of aspiration to the Infinite. I felt it in my heart of hearts.

In this atmosphere and in this environment I used to write my poems of Gitanjali, and I sang them to myself in the midnight under the glorious stars of the Indian sky. And in the early morning and in the afternoon glow of sunset I used to write these songs till a day came when I felt impelled to come out once again and meet the heart of the large world.

—Rabindranath Tagore, Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech

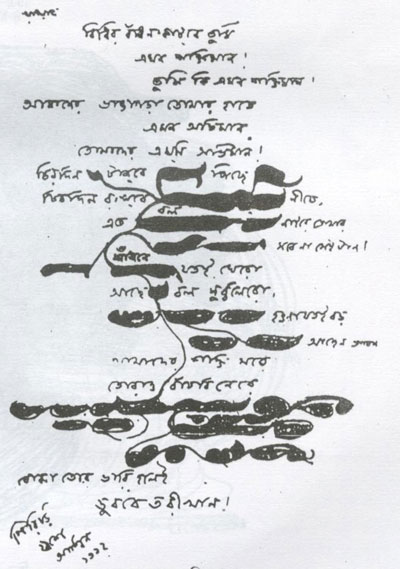

Gitanjali

Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Swedish literary honour in praise of his Gitanjali poems “… because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West.”

Composed from “gita” or song, and “anjali” or offering, the title thus means, “An offering of songs”. The English Gitanjali (1912) is a volume of 103 poems, selected by Tagore from his huge corpus of Bengali verse. Indeed, W.B. Yeats wrote in an introduction to the collection, “[the poems] have stirred my blood as nothing for years …”

And so, herewith a selection of verses from the Gitanjali, which have particular resonance for me.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

IV

LIFE OF MY LIFE, I shall ever try to keep my body pure, knowing that thy living touch is upon all my limbs.

I shall ever try to keep all untruths out from my thoughts, knowing that thou art that truth which has kindled the light of reason in my mind.

I shall ever try to drive all evils away from my heart and keep my love in flower, knowing that thou hast thy seat in the inmost shrine of my heart.

And it shall be my endeavour to reveal thee in my actions, knowing it is thy power gives me strength to act.

XII

THE TIME THAT my journey takes is long and the way of it long.

I came out on the chariot of the first gleam of light, and pursued my voyage through the wildernesses of worlds leaving my track on many a star and planet.

It is the most distant course that comes nearest to thyself, and that training is the most intricate which leads to the utter simplicity of a tune.

The traveller has to knock at every alien door to come to his own, and one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end.

My eyes strayed far and wide before I shut them and said, “Here art thou!”

The question and the cry, “Oh, where?” melt into tears of a thousand streams and deluge the world with the flood of the assurance, “I am!”

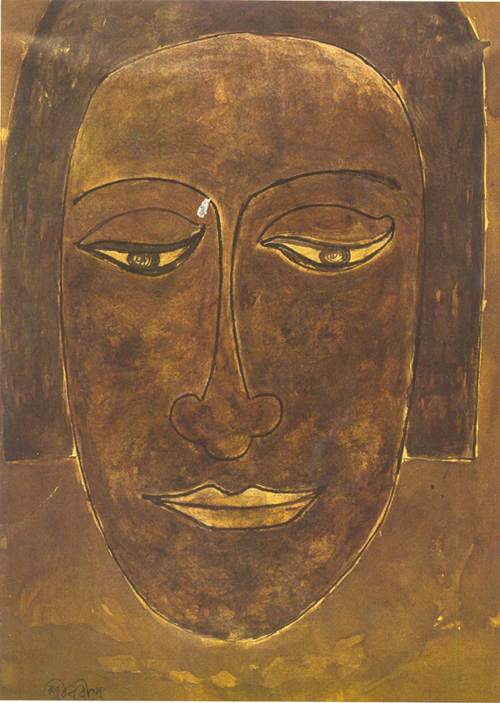

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

XXXI

“PRISONER, TELL ME, who was it that bound you?”

“It was my master,” said the prisoner. “I thought I could outdo everybody in the world in wealth and power, and I amassed in my own treasure house the money due to my king. When sleep overcame me I lay upon the bed that was for my lord, and on waking up I found I was a prisoner in my own treasure house.”

“Prisoner, tell me who was it that wrought this unbreakable chain?”

“It was I,” said the prisoner, “who forged this chain very carefully. I thought my invincible power would hold the world captive leaving me in a freedom undisturbed. Thus night and day I worked at the chain with huge fires and cruel hard strokes. When at last the work was done and the links were complete and unbreakable, I found that it held me in its grip.”

XXXV

WHERE THE MIND is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action—

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

XXXVII

I THOUGHT THAT my voyage had come to its end at the last limit of my power—that the path before me was closed, that provisions were exhausted and the time come to take shelter in a silent obscurity.

But I find that thy will knows no end in me. And when old words die out on the tongue, new melodies break forth from the heart; and where the old tracks are lost, new country is revealed with its wonders.

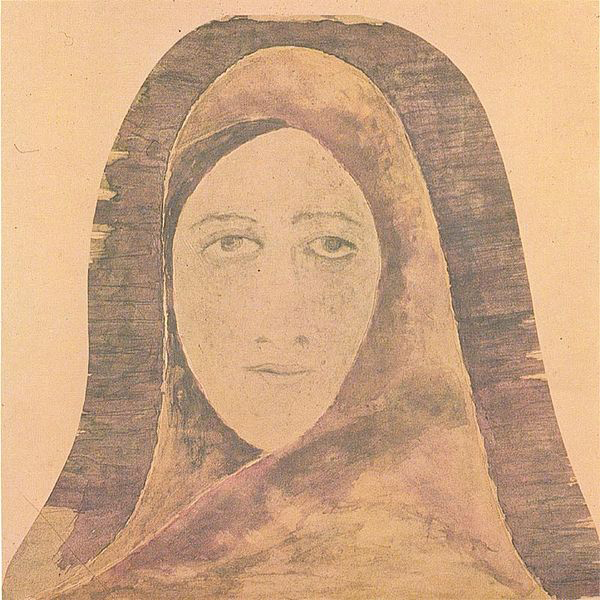

Standing Figure.

Photograph: [Public Domain]

Wikimedia Commons

XLVIII

THE MORNING SEA of silence broke into ripples of bird songs; and the flowers were all merry by the roadside; and the wealth of gold was scattered through the rift of the clouds while we busily went on our way and paid no heed. We sang no glad songs nor played; we went not to the village for barter; we spoke not a word nor smiled; we lingered not on the way. We quickened our pace more and more as the time sped by.

The sun rose to the mid sky and doves cooed in the shade. Withered leaves danced and whirled in the hot air of noon. The shepherd boy drowsed and dreamed in the shadow of the banyan tree, and I laid myself down by the water and stretched my tired limbs on the grass.

My companions laughed at me in scorn; they held their heads high and hurried on; they never looked back nor rested; they vanished in the distant blue haze. They crossed many meadows and hills, and passed through strange, faraway countries. All honour to you, heroic host of the interminable path! Mockery and reproach pricked me to rise, but found no response in me. I gave myself up for lost in the depth of a glad humiliation—in the shadow of a dim delight.

The repose of the sun-embroidered green gloom slowly spread over my heart. I forgot for what I had travelled, and I surrendered my mind without struggle to the maze of shadows and songs.

At last, when I woke from my slumber and opened my eyes, I saw thee standing by me, flooding my sleep with thy smile. How I had feared that the path was long and wearisome, and the struggle to reach thee was hard!

LIV

I ASKED NOTHING from thee; I uttered not my name to thine ear. When thou took’st thy leave I stood silent. I was alone by the well where the shadow of the tree fell aslant, and the women had gone home with their brown earthen pitchers full to the brim. They called me and shouted, “Come with us, the morning is wearing on to noon.” But I languidly lingered awhile lost in the midst of vague musings.

I heard not thy steps as thou camest. Thine eyes were sad when they fell on me; thy voice was tired as thou spokest low— “Ah, I am a thirsty traveller.” I started up from my daydreams and poured water from my jar on thy joined palms. The leaves rustled overhead; the cuckoo sang from the unseen dark, and perfume of babla flowers came from the bend of the road.

I stood speechless with shame when my name thou didst ask. Indeed, what had I done for thee to keep me in remembrance? But the memory that I could give water to thee to allay thy thirst will cling to my heart and enfold it in sweetness. The morning hour is late, the bird sings in weary notes, neem leaves rustle overhead and I sit and think and think.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

LXXX

I AM LIKE a remnant of a cloud of autumn uselessly roaming in the sky, O my sun ever- glorious! Thy touch has not yet melted my vapour, making me one with thy light, and thus I count months and years separated from thee. If this be thy wish and if this be thy play, then take this fleeting emptiness of mine, paint it with colours, gild it with gold, float it on the wanton wind and spread it in varied wonders. And again when it shall be thy wish to end this play at night, I shall melt and vanish away in the dark, or it may be in a smile of the white morning, in a coolness of purity transparent.

LXXXVI

DEATH, THY SERVANT, is at my door. He has crossed the unknown sea and brought thy call to my home.

The night is dark and my heart is fearful—yet I will take up the lamp, open my gates and bow to him my welcome. It is thy messenger who stands at my door.

I will worship him with folded hands, and with tears. I will worship him placing at his feet the treasure of my heart.

He will go back with his errand done, leaving a dark shadow on my morning; and in my desolate home only my forlorn self will remain as my last offering to thee.

XCV

I WAS NOT aware of the moment when I first crossed the threshold of this life.

What was the power that made me open out into this vast mystery like a bud in the forest at—midnight!

When in the morning I looked upon the light I felt in a moment that I was no stranger in this world, that the inscrutable without name and form had taken me in its arms in the form of my own mother.

Even so, in death the same unknown will appear as ever known to me. And because I love this life, I know I shall love death as well. The child cries out when from the right breast the mother takes it away, in the very next moment to find in the left one its consolation.

Post Notes

- Rabindranath Tagore on NobelPrize.org

- Tagore Centre UK

- Visva Bharati University

- National Commemoration of 150th Birth Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore

- Upahar: Bright Like a Million Suns

- Roger Housden: Ten Poems for Difficult Times

- Krishnamurti’s Notebook

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas

- Abhay K.: Anthems for Immortality

- Dennis Gallagher: Towards the Light

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Archana Bahadur Zutshi: Poetic Candour