Gateways to God

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not … And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us (and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father), full of grace and truth. (1:1–5, 14)

—The Gospel According to John

I DISTINCTLY REMEMBER one particularly dreary morning several years ago walking through Victoria Station in London. At the time, I was working for one of the Big Four accountancy firms on the Thames Embankment, writing corporate propaganda and wondering if there could be more to my unfulfilling career and thus, by extension, my own life.

Through the fog of my existential crisis, the window display of a bookshop materialized and caught my attention. Exquisite black and white photography, elegant typography and a collective message from the wisdom of the ancients were calling me hither: the Pocket Canons Bible Series had descended upon earth.

Already having avidly collected classic pocketbooks published by Penguin, celebrating the occasion of their 60th anniversary, I knew immediately I had to possess these superlative things of beauty, which have had pride of place on my desk ever since. Indeed, their minimalist aesthetic gave inspiration to the very design of The Culturium itself.

We are currently living in a time of religious transition. In many of the countries of Western Europe, atheism is on the increase, and the churches are emptying, being converted into art galleries, restaurants and warehouses. Even in the United States, where over ninety per cent of the population claim to believe in God, people are seeking new ways of thinking about religion and practising their faith. In our dramatically altered circumstances, the old symbols that once introduced people to a sacred dimension of existence no longer function so effectively. In the Christian world, some people are either abandoning the old forms, or trying to reinterpret such doctrines as the incarnation or the atonement in a way that makes sense to them at the beginning of the third Christian millennium.

—Karen Armstrong, Introduction to The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Hebrews

Publishers are only too aware of the power of a book jacket, its intent to convey in one singular blink a text’s reason for being and why one’s life would be bereft without it taking up sacred space on one’s bookshelf. A famous example comes to mind regarding the reissue of J. D. Salinger’s masterworks, their sleeves commissioned to celebrated letterist Seb Lester, with their distinctive calligraphy intimating the magnificence of Salinger’s prose by the mere cursive flourish of an understroke.

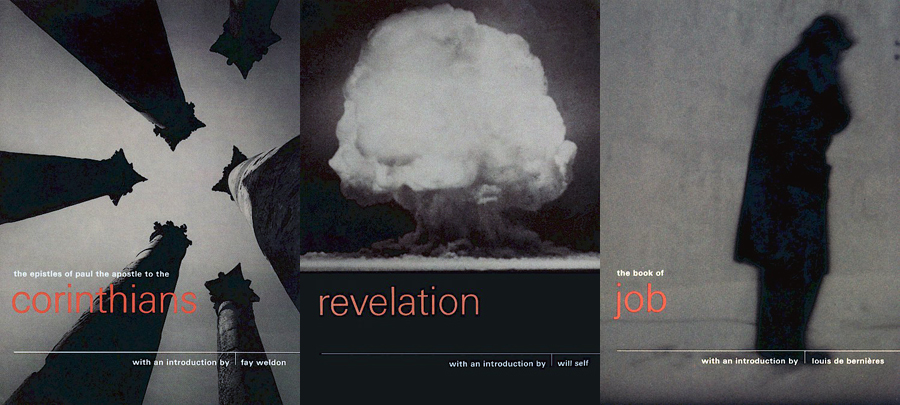

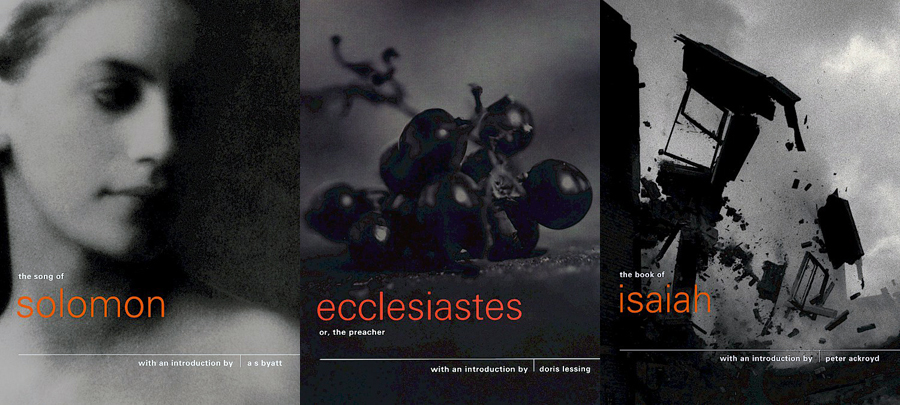

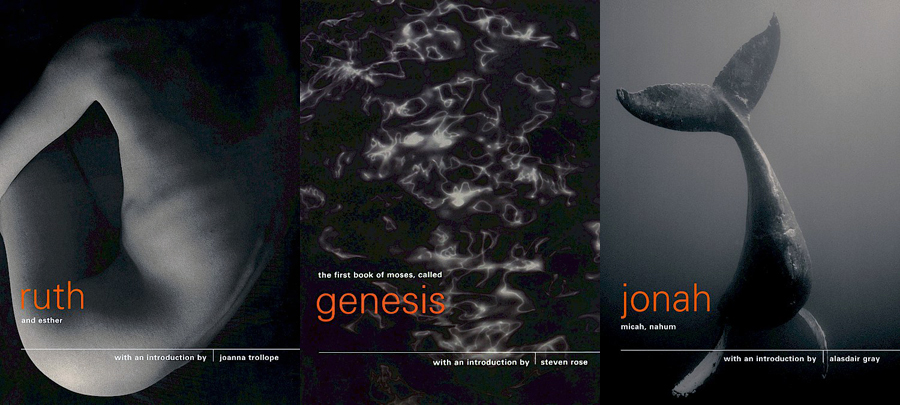

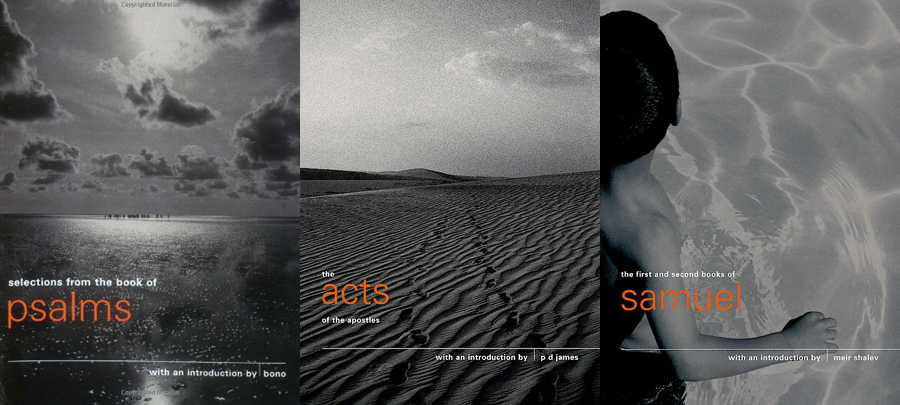

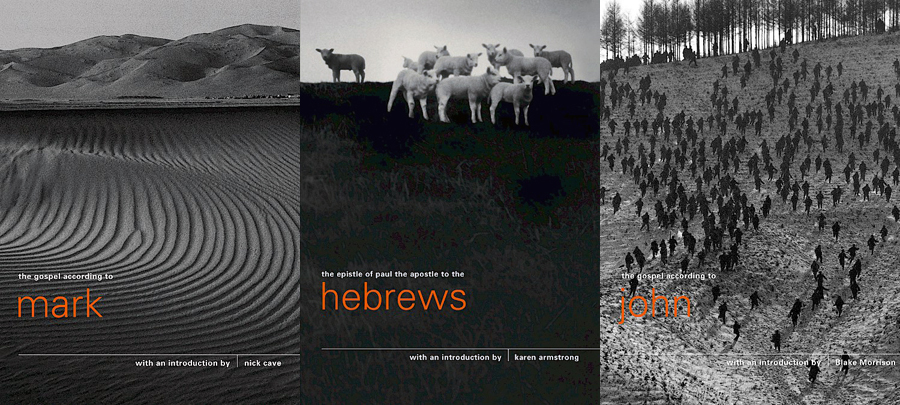

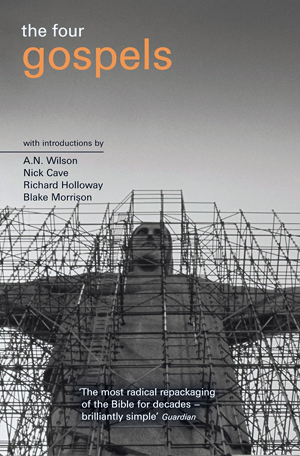

And so too with Canongate’s covers of the Pocket Canons Bible Series—conceived in conjunction with publisher Matthew Darby and conceptualized by award-winning British graphic designer Angus Hyland—that have captivated the public’s imagination with their stunning, timeless artistry and which, after nearly three decades since their first publication, are as arresting as the day they first entered the collective consciousness.

Indeed, in a time period when for most people God is dead, to coin German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s pronouncement about the state of contemporary society, it is truly a wonder that the books of the Bible—that previously antiquated tome resigned to lonely hotel nightstands and provincial secondhand bookshops—have become associated with one of the most celebrated moments in book publishing history.

The epistle [of James] begins by underlining the critical importance of developing a single-pointed commitment to our chosen spiritual path. It says, ‘A double-minded man is unstable in all his ways’ (James 1:8), because lack of commitment and a wavering mind are among the greatest obstacles to a successful spiritual life. However, this need not be some kind of blind faith, but rather a commitment based on personal appreciation of the value and efficacy of the spiritual path. Such faith arises through a process of reflection and deep understanding. Buddhist texts describe three levels of faith, namely: faith as admiration, faith as reasoned conviction, and faith as emulation of high spiritual ideals. I believe that these three kinds of faith are applicable here as well. The epistle reminds us of the power of the destructive tendencies that exist naturally in all of us. In what is, for me at least, the most poignant verse of the entire letter, we read, ‘Wherefore, my beloved brethen, let every man be swift to hear, slow to speak, slow to wrath: for the wrath of man worketh not the righteousness of God’ (James 1:19–20).

—The Dalai Lama, Introduction to The Epistle of James

Not everyone, however, was so enthralled with their release. At the time of the first print run back in 1998, a certain self-appointed leader of a Christian ministry, proclaiming Jesus is alive and well and living amongst us, orchestrated a hate campaign, trying to do everything in his power to prevent the series from being published. After a failed attempt to take Canongate to court on the charge of blasphemy, the religious fanatic proceeded to send letters to every single parish in the UK, warning them about the books and urging ministers to write to Canongate’s CEO and Publisher, Jamie Byng, personally, to withdraw the texts altogether.

One must pause here awhile to remember that, to paraphrase another German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, “truth” passes through three distinct stages when it has revolutionary implications as a life-changing idea: first, it is ridiculed; second, it is violently opposed; third, it is accepted as being self-evident. Indeed, despite receiving disturbing correspondence decrying that Canongate would burn in eternal hellfire, there was a similarly enthusiastic show of support, encouraging the publisher to ignore the deluded zealot, unequivocally stating that the Pocket Canons were the best thing to happen to the Bible in decades.

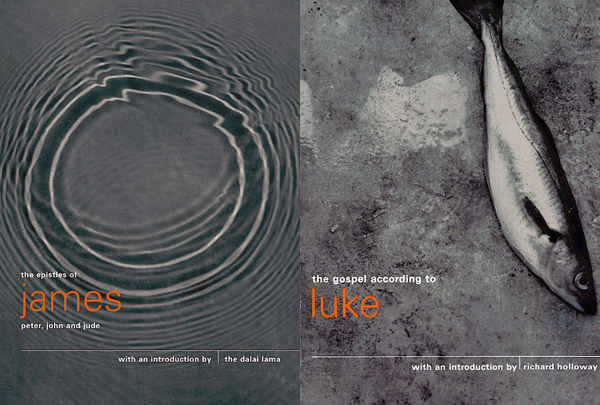

And thus the Pocket Canons Bible Series was born, comprising 12 small, stand-alone volumes from one of the world’s most sacred libraries of devotional literature: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Job, Corinthians, Song of Solomon, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Genesis, Revelation and Exodus. Such was its success, that a second series of 10 titles was published a year or so later: Acts, Romans, Hebrews, Wisdom of Solomon, Jonah (together with Micah and Nahum), Isaiah, Psalms, Ruth (together with Esther), James and Samuel. Thereafter, a final compilation was put together in 2010 consisting of the Four Gospels in one single volume produced in the more conventionally sized paperback format.

I read The Book of Revelation once—I never wanted to read it again. I found it a sick text. Perhaps it’s the occlusion of judgemental types, and the congruent occlusion of psyches, but there’s something not quite right about Revelation. I feel it as an insemination of older, more primal verities into an as-yet-fresh dough of syncretism—the Neoplatonists still kneading at the stuff of the messiah. The riot of violent, imagistic occurrences; the cabalistic emphasis on numbers; the visceral repulsion expressed towards the bodily, the sensual and the sexual. It deranges in and of itself, and sets the parameters, marshals the props, for all the excessive playlets to come. In its vile obscurantism is its baneful effect; the original language may have welded the metaphoric with the signified, the logos with the flesh, but in the King James version the text is a guignol of tedium, a portentous horror film.

—Will Self, Introduction to Revelation

What made the series so spectacularly popular, even controversial, was the fact that each pocketbook was graced with a newly commissioned introduction by an eminent author, musician, theologian or scientist, who was not afraid to let rip their innermost feelings about the mighty Good Book: Doris Lessing (Ecclesiastes), Louis de Bernières (Job), A. S. Byatt (Song of Solomon), David Grossman (Exodus) and Bono (Psalms), to name but a few.

For me, of particular fascination were the forewords composed by Will Self and his poignant eulogy to his manic-depressive friend who died of a heart attack brought on by an involuted life (Revelation); an irascible yet soul-searching Nick Cave meeting an Anglican vicar who advised him to read Mark “because it’s short” (Mark); and a rebellious Blake Morrison preferring the Fab Four of the Beatles to the Apostles after a childhood confined to the choirstalls of an English country village church (John).

Most specifically, Steven Rose’s seemingly irreverent prologue appears to outline the radical motive behind the reason why each writer was handpicked to collaborate with Canongate: “Did the editors of this series of volumes of the King James realize that I was an ex-orthodox Jew, an atheist and a biologist to boot when they suggested that I write this introduction? Yes, they said, and that’s why we asked you” (Genesis).

Wisdom has gone out of fashion. The very word is one of a number in the English language that we find frequently in works of literature but seldom in everyday life. In the half-century that has passed since I reached the age of reason, I can scarcely remember ever having heard a philosopher, statesman or indeed anyone else described as wise. Our most common terms of approbation tend to be ‘intelligent’, ‘clever’, ‘astute’, ‘shrewd’ or ‘high-powered’. The skills of our rulers lie in reading the runes of focus groups and opinion polls, and the image they want to project is of someone vigorous, forceful, youthful, dynamic—not wise. In the academic world, professors are appointed for their specialist knowledge, not their overall sagacity, and university chancellors are chosen more for their abilities as administrators and fundraisers than as the elders of their people. Even philosophers who, from the etymology of the word that denotes their calling (love of wisdom), might be expected to give it some meaning, are no longer wise. Continental philosophers spew out incoherent gibberish while British linguistic philosophers have narrowed their focus to the point of irrelevance.

—Piers Paul Read, Introduction to The Wisdom of Solomon

Such is the modus operandi behind Canongate as a publisher overall. Describing itself as “fiercely independent … committed to unorthodox and innovative publishing”, it is a blessed relief to know that amidst the relentless tide of airport pap, chick-lit nonsense and absurdist psychobabble, discerning literature is still transporting readers through the gateways of truth, beauty and wisdom.

Since 1973, when the company was first founded, there have been landmarks of literary merit, including Alasdair Gray’s masterpiece Lanark, Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, the collected works of Tan Twan Eng (The Gift of Rain, The Garden of Evening Mists and The House of Doors) and, most recently, Stephen Nachmanovitch’s Free Play.

Having just celebrated its own 50th anniversary, Canongate continues to cultivate not only its list of groundbreaking titles but also promulgate its core creation, the Canons, which embody all the classic elements of a timeless and iconic work of art or literature.

There is a human experience that sometimes captures the mystery that haunts us. Music is usually held to be the experience that does this best. In music there is an almost perfect equivalence of form and content. Music evidences itself, is itself the experience we experience, and is not just a sign or a symbol for something else. All great art does this. It breaks through the frustration of language and unites us with that which words only usually signify. I say, ‘only usually’, because there is a language that, like music and art, is also capable of this same perfect tautology, this mysterious equivalence between the longing and the thing longed for. I am, of course, talking about poetry. Art, particularly music and poetry, unites us with the thing beyond, places us in its midst, rather than talks unceasingly and ineffectively about it, which is what religion does.

—Richard Holloway, Introduction to The Gospel According to Luke

This all still begs the fundamental question, what is the actual point of reading books of the Bible today? One could argue they form part of the foundational triad of Western civilization, together with the Classics (ancient Greek and Latin literature, philosophy and history), as well as the collected works of William Shakespeare. The invention of Gutenberg’s printing press and Timothy Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web have only served to propagate further the dissemination of their message, making the Bible the best-selling book of all time.

The answer to this mysterious question lies predominantly I believe in the fact that the emergence of the Authorized King James Version of the Bible (translated between 1603–11), which is the official text used in the Pocket Canons Bible Series, coincided with an unprecedented flowering of English literature during the Renaissance period and, as such, had a profound influence, more than any other text in existence, in shaping the language in which we speak, write and even think in our modern-day culture.

Indeed, the brilliant writer George Orwell, who understood how the misappropriation of language can control and manipulate the minds of the populace for political power and religious submission, reminds us how vital it is to return to the source of things, never take concepts out of context and, above all, develop the faculty of reasoned discrimination for ourselves.

The Bible is, above all, a work of literature and we approached people who we felt would read it as such. It was in response to the King James Version that they wrote the introductions that follow and the range of ideas expressed and experiences recounted is broader than any church that I know of. Some of the pieces are extremely personal but all of them are heartfelt and the wonderful array seems to me to epitomize what the whole project was about—celebrating language, encouraging dialogue and respecting the individual.

—Jamie Byng, Introduction to The Four Gospels

Post Notes

- Images: © Canongate

- Stephen Nachmanovitch: Free Play

- Gospel of Mary Magdalene

- J. D. Salinger: Franny and Zooey

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Instant Light

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Kahlil Gibran: Poet, Painter, Prophet

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme