Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

Dispelling illusion

In the third and final extract from her book, The Teachers of One, in which she documents her very first spiritual journey to India, Paula Marvelly, Editor of The Culturium, ascends Mount Arunachala to sit in Virupaksha Cave and experience the oneness of the Self.

“Those who have sunk deeply into the ocean of silence and drowned will live on the summit of the supreme mountain, the expanse of Consciousness.”

—Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi

THE LIFE OF Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi was immaculate humility and benevolence. He showed compassion to all beings—animals, thieves, people from all castes, religions and creeds. He refrained from getting involved in worldly activities; he never handled any of the ashram money nor did he answer letters addressed to him, though he would always welcome anyone into his presence.

Ramana also wrote down very little of his teaching. The only verses which arose spontaneously were Eleven Stanzas to Sri Arunachala and Eight Stanzas to Sri Arunachala; the rest of his poetry being produced specifically at the request of a disciple to elucidate a particular point—put altogether as a collection, it only forms a slim volume. And his most well known work, Forty Verses on Reality or Ulladu Narpadu, together with its forty supplementary verses, constitutes just over ten pages of written text. “All this is only activity of the mind,” he remarked to a visiting poet. “The more you exercise the mind and the more success you have in composing verses, the less peace you have.” Nevertheless, he did meticulously edit the books published during his lifetime to ensure accuracy of meaning, leaving no room for misunderstanding or misinterpretation.

No possessions, no money, I reflect. No hypocrisy or hidden agendas, no egotism or conceit. No relationship scandals, no money scams. No abuse of power, no deceit. Absolutely nothing about the way in which Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi lived his life can be misconstrued. How I wish I could have met him, received his blessing, his upadesa, his smile.

Indeed, the Buddha asserted that in the end, everything must be given up. Should this not be taken literally, as Ramana’s life seems to suggest? I appreciate that living in the Western world, a hemisphere so locked into economic and material dysfunctionalism, money and possessions are an intrinsic part of life. But it is not easy to use that argument simply to justify having the things around us? If we truly renounce everything, would not all our needs be provided for, no matter where we lived, as the life of Ramana proved? When asked about this point, however, Bhagavan was quite specific—nothing needs to be given up, he said, merely the thought, “I am the doer”, replacing it with, “I am”. Moreover, when asked about which was the higher path, life as a householder or that of an ascetic, he replied, “Was not Rama spiritually advanced and was he not leading a householder’s life?”

Nonetheless, the likes of Ramana are rare indeed. A teacher of such calibre only comes, some would say, every five hundred years. Ramana himself spoke of the differences in absorption in the Self, which can be either temporary or permanent. Nirvikalpa samadhi Ramana likened to a bucket lowered into a well; the water in the bucket merges with the water in the well but the rope and bucket (representing ego and its attachments) still exist, meaning that the bucket can always be pulled out from the well, ending the total absorption. Meanwhile, sahaja samadhi he likened to a river flowing into an ocean, whose waters become inseparably merged. Ramana’s sahaja samadhi happened spontaneously at the age of 17—for me, is nirvikalpa samadhi all I can really hope for?

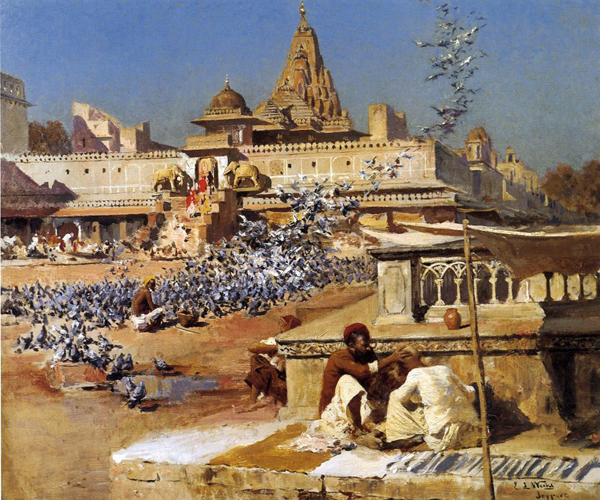

The Temples and Tank of Walkeshwar at Bombay.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

Indeed, a guru is needed to dispel the illusion of ignorance, though in rare cases the guru does not necessarily need to be in human form: “The outer guru gives the mind a push inwards and the inner guru pulls it,” Bhagavan said. Thus, Ramana’s presence was only to initiate devotees on the path, either by his speech, his look or through sitting in silence. Accusations of inconsistency in his instruction have been made but these apparent contradictions highlight the way in which Ramana taught at the level of the understanding and emotional disposition of the aspirant.

He employed two approaches to abiding in the Self: either jnana marga, the path of knowledge, through the method of vichara (Self-Enquiry) or bhakti marga, the path of devotion and surrender. “There are two ways: either ask yourself, ‘Who am I?’ or submit,” he would say, knowing that intrinsically, jnana and bhakti lead ultimately to the same end. “The eternal, unbroken, natural state of abiding in the Self is jnana. To abide in the Self you must love the Self. Since God is in fact the Self, love of the Self is love of God, and that is bhakti. Jnana and bhakti are thus one and the same.”

For the Western mindset, intent on philosophical analysis and intellectual debate, Ramana prescribed Self-Enquiry as the most effective path, though it is paradoxically deemed to be the harder of the two methods: first, owing to its simplicity and directness; and secondly, because it breaks down the apparent veil of dualism (dvaita) that devotion and compassion between guru and devotee (from the point of view of the devotee) can bring about.

Fixing one’s attention on the centre of consciousness in the body, the spiritual heart (which Ramana believed is on the right side of the chest and not the left, where the physical heart is located), a current of awareness of “I” will arise. Through constant vigilance, when a thought arises, one should ask, “Where did this thought come from, and why, and to whom?” This then leads to the final question, “Who am I?” The answer will then be revealed but it will be beyond all words, concepts and thoughts: ‘Self-Enquiry is like the thief turning policeman to catch the thief that is himself.” Bhagavan was also specific about the need for constant spiritual effort: “If you strengthen the mind, that peace will become constant. Its duration is proportionate to the strength of mind acquired by repeated practice.”

Nevertheless, he also stated that events in one’s life were attributed to one’s prarabdha karma that is to be worked out in this life: “As beings reap the fruit of their actions in accordance with God’s laws, the responsibility is theirs, not His.” Asked about this apparent contradiction between destiny and effort by a devotee, he replied: “That which is called ‘destiny’, preventing meditation, exists only to the externalized and not to the introverted mind. Therefore, he who seeks inwardly in quest of the Self, remaining as he is, does not get frightened by any impediment that may seem to stand in the way of carrying on his practice of meditation. The very thought of such obstacles is the greatest impediment … The best course, therefore, is to remain silent.” And again, he said, “All the actions that the body is to perform are already decided upon at the time it comes into existence: the only freedom you have is whether or not to identify yourself with the body.”

Devoid of ritual and priestly hierarchy, cosmology and dogma, the teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi are as appropriate for the man in the ashram as for the man in the office or home. Nevertheless, Self-Enquiry is not for the faint-hearted—it is for those who truly wish to go all the way home: “It is intended only for ripe souls,” Bhagavan said, conceding that some devotees need to adopt less direct methods more suited to their spiritual development. Nonetheless, when a devotee asked for permission to drop the methods he had been using up until that moment, Bhagavan replied, “Yes, all other methods only lead up to the vichara.”

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

As we make our way up and up, we start to talk about the different teachers I have met and Bharat asks me what conclusions I have come to. “I am still finding this paradox difficult to get hold of,” I say, trying to catch my breath. “Gangaji says you can choose to be free. Ramesh says it is in your mind-body programming whether you will be free or not.” Bharat laughs, understanding the familiar conundrum. “Both exist,” he says as we stop to rest by some large red boulders to take a slug of water. “You must make a commitment to the truth, one hundred per cent. But at the same time, ask yourself whose destiny is it and who makes that commitment? It’s about opposites co-existing … It’s all there in the teachings of Ramana.”

I continue to reflect on all the many interpretations of the same nondualistic truth I have heard. On the one, hand there is the more experiential approach of Papaji’s messengers, choosing to surrender to what is. On the other hand, there is the intellectual rigour of Self-Enquiry, principally coming from the Ramesh line, leading to an understanding of what is. And yet both approaches are accommodated within the teachings of Bhagavan. In him, seemingly everything is contained.

We set off again. A bare-chested sadhu wearing only a white dhoti, his naked torso the colour of beaten bronze, namastes to us as he passes by. His forehead is daubed with holy ash with a vermilion gash of paste blobbed between his eyebrows. Further along the path, a young boy has set up a stall of small statues, which he carves by the edge of the path. He beams excitedly as we approach—would we like to buy a statue of Siva, Hanuman, the wheel of Kali, Ganesh? I examine one of the pieces, a small carving of the elephant god, delicately chiselled in grey-blue stone. I buy it from him and he returns the transaction with a wide smile of brilliant white teeth.

After nearly an hour of walking, the path plateaus out, affording a stunning view over Tiruvannamalai, which stretches for miles across the plain into the distance. And in the middle of this panoramic sea of buildings and urban sprawl, rises up the Temple of Arunachaleswar, a shrine to Ishvara, the personal God. It is probably the most breathtaking man-made structure I have ever seen in my life, our position on the hill rendering us even more of a spectacular view than that from the ground. Dating from the 11th century CE, its fortress structure has four large gopurams or towers, rising to over 60 metres high, like huge electricity pylons waiting to conduct the very force of God from the heavens above.

In India, worshipping God and his manifestation is part of everyday life. Hinduism is practised by approximately 80 per cent of the population, which represents more than 700 million people. To outsiders, it can appear to be a complex amalgam of conflicting philosophical theories as well as possessing a bewildering pantheon of goddesses and gods. At its heart, however, there is a central belief—Brahman, impersonal awareness, manifested within itself to become Ishvara, the personal god. Ishwara has three aspects, the trimurti, namely Brahma (the Creator, married to Saraswati), Vishnu (the preserver, married to Lakshmi and reincarnating as Rama and Krishna) and Siva (the destroyer, married to Parvati). Which god or goddess one chooses to worship is ultimately a matter of personal taste, tradition or caste, though, if sincerely practised, all ways lead to the ultimate state of absorption in the Self.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

We pass through a gate and slip off our shoes. Skandasramam is a small grove where there are steps of rock to sit on to bask in the visionary beauty laid out before us. Dragonflies flit here and there and the air is filled with the music of running water, coming from a small spring at the back of the courtyard. We take the opportunity to rest and gather our thoughts, or lack of them, under the shade of sheltering trees, where the light on the ground reminds me of drops of liquid gold, like daubs of cyan in the paintings of the Impressionists. How easy it would be to find liberation in this Garden of Eden, I think.

On the left of the dwelling is a small ante-room—above the doorway is a plaque which reads, “The Holy Room / The Soul of Mother Attained Nirvana”. Outside the main building, there is a verandah, protected by emerald-coloured grilles and a corrugated roof. Inside, we pass into a small cool room. The doorway is low and, forgetting my relative height, I knock my head against the lintel. On the walls are black and white photographs of Ramana.

In front of us is a much smaller room, where a handful of people are kneeling or sitting in the lotus posture in front of a small shrine to Bhagavan. Once more, the modesty and understatedness move me indescribably. There is a photograph of Ramana in the centre, flanked either side by a picture of Arunachala and a small book revealing his teachings. Even the candle placed in front of him burns with a graceful humility. I kneel before Bhagavan and then return to the outer room, where I sit and experience the sanctity of this holy place. The silence is so palpable that even the thinking of a thought would be a deafening noise.

There is a sadhu called Skandaswami who looks after the dwelling. He sits on the shaded verandah, fanning himself with reeds. I notice a pamphlet propped up in one of the window frames—it is Who am I?, Bhagavan’s teaching and I start to copy out some of its contents. Skandaswami notices what I am doing and offers the booklet to me to keep. I am deeply touched, I motion with my hands, but decline—how could I possibly remove something from this sacred place?

Virupaksha Cave, Ramana’s main residence for 17 years during his time on the hill, is a short descent from Skandasramam but the heat is rising as the morning sun climbs in the sky. Bharat and I decide, therefore, to return to the ashram in time for lunch. We hardly speak on our way back—there doesn’t appear to be any need for words.

The following day, again shortly after breakfast, I take the same journey up the hill, this time accompanied by a South American girl, backpacking around India. We encounter bare-footed disciples, swamis and sadhus along the way. Then we pass by Skandasramam to the tapping of the statue seller’s hammer and chisel and negotiate the path that leads down to Virupaksha Cave. We cross over the small stream that cascades down the hillside and descend down steep steps, past rocks and tropical foliage. We move around a huge boulder and there, in front of us, is the place where all my wanderings have led. My heart is pounding. There is a gateway into a courtyard surrounding a small white building, which looks out over Tiruvannamalai and Siva’s Temple. The bows of trees hang over the compound, in which monkeys squabble and stare at me with their blushing faces. I take off my shoes and enter the dwelling under a plaque hanging over the door, which reads, “Virupaksha Cave / Sri Ramana Maharshi stayed here from 1899 to 1916”.

A sadhu is resting inside and he rises silently to greet me. The floor is red and pink and on it there is an Indian mandala—a lotus flower surrounded in a circle, made from blue and grey stone. On the walls are black and white photographs of Ramana as a young boy and later as a swami. There is also a stone couch where he slept, indicated by the sadhu pointing first to it, then to a picture of Ramana and then putting his hands together under his cheek. The sadhu then escorts me into a dark room with a tiny doorway, where we have to duck right down to get through. It takes many moments for my eyes to adjust to the darkness. The sadhu leaves, returning with a cushion, indicating where I should sit. A handful of people seem to emerge from the darkness, all deep in meditation. Even my breathing seems to be a disturbance and I silently practise pranayama to steady my breath.

Where the building ends is the rock of the cave. Part of the rock wall bulges into the room, forming a ledge on which there is a picture of Arunachala, surrounded by a garland of white flowers. There are also burning candles and a dish of holy ash. The sadhu beckons me towards him as he lifts a cloth covering the rock. He rubs it with his hand, generating a greyish powder. He smoothes it between his fingertips and then rubs it onto my forehead. I feel honoured by this simple ceremony, that my body has been baptized by the very earth of sacred Arunchala from the tomb of the great sage, Virpakshadeva, and where Ramana was absorbed in sahaja samadhi.

I return to my seat and immerse myself in deep meditation. The silence of the cave consumes me. But whereas the silence in Skandasramam embraced everything in the world around me—its sights and sounds and smells—it was the merging with the silence of Prakriti. And yet here, with my eyes closed in the darkness, the silence has a depth and profundity I have never experienced before. Everything has been absorbed back into a blankness, a void, into the unmanifest spirit of Purusha. At first, it feels disconcerting and unfamiliar. The cave is damp and the faint smell of incense makes my head feel giddy.

As in my dream of a few nights back, the oily darkness seeps into my skin, filling up orifices and pores and I drown in a sea of blackness. But this is not the anaesthetized withdrawal into the unconscious that sleep brings. Now, I am fully present, fully awake—a witness to the withdrawal of creation happening within me. My thoughts and feelings have died and the world passes away. Time stops. The universe dies. Nothing remains. I exist no more.

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

Once again, we namaste. As I prepare to leave, he lingers by my side. I realize that the etiquette now is for me to offer a financial donation. But this particular day, I have left all my money and valuables in the ashram safe and have absolutely nothing to give him. I try to explain that I want to offer him some rupees but that I don’t have any on me. Suddenly, I feel quite wretched. Even though the ashram specifically states that one shouldn’t give money to sadhus on the hill and that any donations should only go through the ashram cashier, I still feel I have committed some awful faux pas, taken kindness from this modest and benevolent sadhu without giving anything in return. He waves his hand to show me that he has understood and returns to his chair, looking despondently down at the floor.

The pangs of anxiety and regret linger in my heart the entire journey down the hill to the ashram. Indeed for days, it plays on my mind and I consider whether I should go back to the cave to offer Subramanian a donation. But the two trips up the hill have left me physically exhausted and, reluctantly, I make the decision not to return.

The days pass, each one blending into the next. I spend many hours relaxing in my room, reading, writing and trying to recuperate from my sickness, somewhat hindered by the fact that I am bitten on my lower left leg by a scorpion, resulting in my skin turning an alarming shade of red. But for most of the time, I stay well within the ashram precincts, not venturing out into Tiruvannamalai. The bustle of the main street running past the ashram is enough for me to taste southern Indian life. My favourite time of the day is tiffin, which is served in a room adjacent to the dining hall. I take two metallic cups and an Indian man ladles a stream of milky tea into one of them. I discover the ritual is to continuously pour the tea from one cup to the other and the higher the distance between the cups the better, enabling the air to cool down the temperature of the tea. It is absolutely delicious.

It is my last evening in the ashram. Dinner is at seven-thirty. The Doctor helps out with the seating arrangements and when the food is distributed, Mr Ramanan serves everyone with ghee, which he pours over the rice. The food is particularly tasty this evening—soup, rice and vegetable curry, poppadums and pickle, followed by sweet rice, caramel papaya and a banana, buttermilk and curds.

I decide to spend the evening in the Old Hall, the main meditation room where Ramana lived and gave satsang between 1925 and 1949. It is a modest room, tucked under the shade of a frangipani tree with large yellow flowers. Inside there is a stone floor, green shutters and an elaborate ornamental dado running around the walls. I am shocked by the number of people I find inside since the silence is so loud you could hear a pin drop. I find a gap by the wall and sit against it and close my eyes. Everything is so still.

The focus of the room is Bhagavan’s couch, covered in Indian shawls, where he spent so many years dispensing his wisdom. A large framed hand-coloured black and white photograph of Ramana now resides in his place, depicting him reclining against some pillows with his long thin legs stretched out in front of him. It makes me smile to see this charming attempt to evoke the memory of his presence.

As peace overwhelms me, I hear the faint purring of the overhead fan and the pulse of the crickets in the outside grass. There is nowhere to go, nothing to do, I reflect once more. I then start to think about my journey home, re-entry into my so-called life. Sadness wells up in my heart—I don’t want to leave this holy place. If only I could preserve this moment and carry it back with me forever. Then I think about what Ramana said when he was approached by a devotee, upset at her imminent departure from the ashram. “Why do you weep?” he said to her, “I am with you wherever you go.”

The following morning as I pack my things to leave, I reflect on something I have read in one of Ramesh’s books that I have brought with me. First, there is a mountain, he says. It is perceived as being real because there is total involvement. Second, the next stage, is that there is no mountain because everything is seen as unreal, not having a self-subsistent reality. Finally, the last stage, is that there is a mountain. It is perceived as being real because consciousness is seen as manifesting as a mountain. It reminds me of something else I have long since read—a quote from the Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time

—T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding”, Four Quartets

As my taxi pulls away taking me back to Chennai, I look back at Arunachala in all its splendour, reaching up into the brilliant blue sky. I close my eyes, trying to burn the image on the back of my eyelids. I then turn around and look out to the open road ahead of us. “In the end, everyone must come to Arunachala,” Bhagavan said. It is true, I reflect, for this is the end of my exploring and yet I shall never cease from my exploration of this most blessed life.

[Extract: Paula Marvelly, The Teachers of One: Conversations on the Nature of Nonduality]

Photograph: [Public Domain] The Athenaeum

Post Notes

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Saint

- Alan Jacobs: Who Am I?

- Ana Ramana: Hymns to the Beloved

- Upahar: Bright Like a Million Suns

- Paula Marvelly: A Singular Man