Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

In search of bliss

In the second extract from her book, The Teachers of One, in which she recounts her very first spiritual journey to India, Paula Marvelly, Editor of The Culturium, is now safely installed in the Ramanasramam and imbibing the sacred atmosphere of the home of India’s greatest sage.

“The mind is only a bundle of thoughts. The thoughts have their root in the I-thought. Whoever investigates the True ‘I’ enjoys the stillness of bliss.”

—Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi

I WAKE UP and leap out of bed, panting and thrashing about like a madwoman. It takes a few moments to realize where I am. It was all just a dream, I tell myself. But it was so very real whilst it was all happening. And now, another dream surrounds me. When will I wake up from this one, I wonder?

The following day, I join other devotees in the Main Hall for the morning milk offering to Sri Bhagavan at his Samadhi Shrine. Opened by Indira Gandhi, it is a large, slightly austere auditorium, with a marble floor and cream and green painted walls. At the end is Bhagavan’s shrine—a life-sized statue of Sri Ramana sitting in the lotus position, carved in black onyx-textured material, is centred on a raised stage, surrounded by a balustrade. Incense billows into the air from burners and multifarious-coloured flowers are scattered all over the shrine. There are also portraits of Bhagavan drenched in garlands and various gods and goddesses standing like sentinels, protecting their Lord, whose body is entombed under the altar. Rather than being cremated as is the usual tradition in India, Ramana’s body has been preserved so that people may still benefit from his presence.

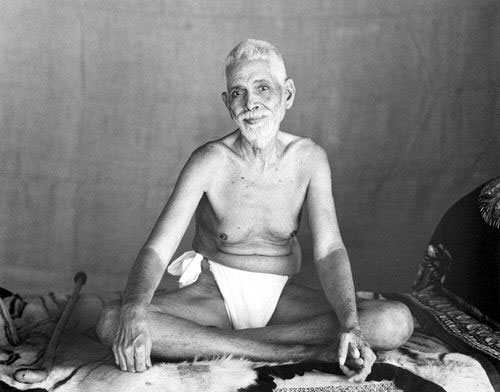

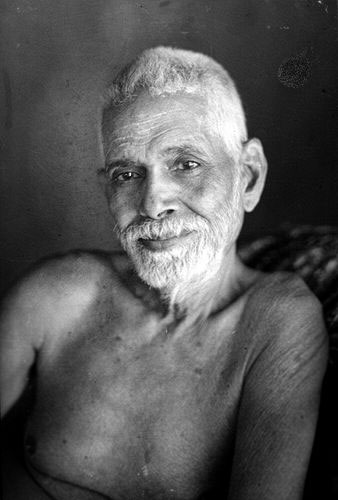

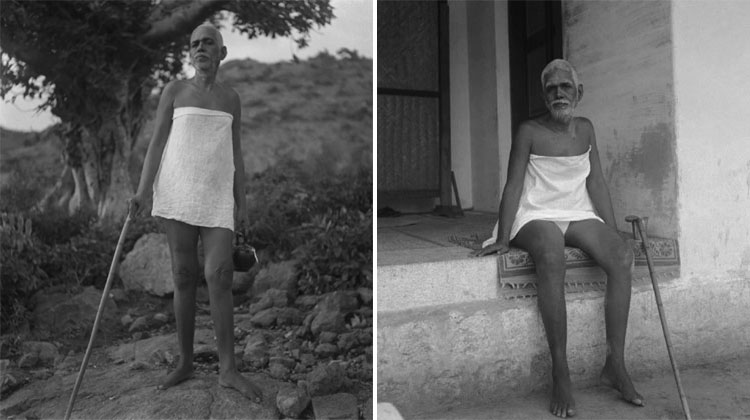

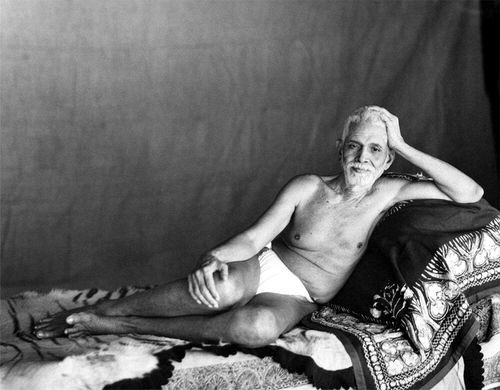

The hall is adorned with photographs of Ramana, sitting on tiger skin rugs or walking with his stick. There are also the famous black and white portraits, taken by G. G. Welling, a photographer from Bangalore. The story goes that when Welling was about to take the photographs, Ramana asked whether there was sufficient light, to which Welling replied, “Bhagavan, you are the light!” By the hall’s back entrance is the most well-known picture of them all—a head and shoulders shot hanging in a mahogany frame. His face is mesmerizing—so full of compassion and possessing a childlike innocence. His eyes follow me around the room but I am not unsettled by this, rather I feel that his gaze affords some form of protection. If only a mere photograph can have such an effect on me, what would it have been like to look right into his eyes, to have been so close to his physical presence?

An Indian man starts to sing sacred incantations and then people kneel or prostrate themselves on the floor. A flame in a small dish is then waved around the shrine—a ceremony known as arati. He turns towards the congregation and everyone gathers around him, putting their hands over the flame and then placing their palms on their heads. Under the burning wick are turmeric and vermilion-coloured powder, which I mix between my fingertips and then rub onto my forehead. Everyone then files clockwise around the shrine—some walk slowly and reverentially, others with a spring in their step. When we finish the turn, an Indian man holds out a ladle of milk prasad, which I receive in my cupped hands. I drink the sweet liquid, though half of it streams down my face.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Throughout certain periods of the day, the Vedas are chanted in front of this shrine. The sound has a drone-like quality, both somnolent and hypnotic. Indeed, it is the Vedas which form the written source of Ramana’s nondualist teaching. They are the oldest scripture known to mankind, dating maybe as far back as 5000 BCE and predating even the Bible. The Vedas (meaning knowledge) are made up of four texts: the Rig Veda (hymns and the main Vedic philosophy); the Yagur Veda (sacrificial formulae); the Sama Veda (melodies); and the Atharva Veda (spells and incantations). Each Veda consists in turn of four parts: Samhita (hymns and prayers); Brahmanas (sacrificial rituals for householders); Aranyakas (meditations for forest dwellers); and Upanishads (philosophical debate). The Vedas are believed to be divinely inspired scriptures, known as sruti, which are revealed through the writings of poets, priests and philosophers. Indeed, Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, as well as their indigenous offshoots, all owe their philosophical roots to the Vedas.

In order that the teaching is more accessible to all, allegorical renderings or smrtis were compiled. Rather than being overtly stated, the philosophy of the Vedas could be implied through storytelling. Written as literary epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which incorporates the Bhagavad Gita, were therefore able to make the teaching more available to a wider audience. Nevertheless, scholasticism still prevailed and the doctrines of six distinct schools of Indian thought started to emerge and to be documented. Despite their metaphysical roots coming directly from the Vedas, the principal school, Uttara Mimamsa, developed its system based on the philosophy found primarily in the Upanishads, thus becoming more commonly known as the school of Vedanta, meaning “the end of the Vedas”.

In order to clarify the vast array of interpretations, many commentaries were written on the philosophy of the Vedanta, which was now concentrated into a specific text, called the Vedanta Sutra (or Brahma Sutra), compiled by Badarayana, a pupil of Gaudapada. The most famous commentators on the Vedanta Sutra were Shankara (8th century CE), Ramanuja (11th century CE) and Madhva (13th century CE). And although their commentaries were also rooted in the same Vedic philosophy, they developed their own distinctive systems of interpretation, namely Shankara’s nondualism (Advaita); Ramanuja’s qualified nondualism (Visistadvaita); and Madhva’s dualism (Dvaita). It is Shankara’s Advaita that has prevailed, becoming the most widely accepted commentary on Vedic philosophy. His interpretation can essentially be reduced to the following three, seemingly paradoxical, statements: “Brahman is real; the universe is unreal; Brahman is the universe.”

It is said, nevertheless, that the teaching was revealed long, long before any recording in the Vedas. As well as manifesting as Arunachala mountain, Siva also appeared in human form as the primal sage, Dakshinamurthi—a young illuminated teacher who would teach in silence, initiating and guiding his elder disciples by direct transmission of the Self. Legend has it that throughout the ages, Dakshinamurthi has been sitting on the north slope of Arunachala, underneath a banyan tree and that anyone who approaches him will attain Self-realization. Indeed, Ramana acknowledged the sagacity of this primal teacher, proclaiming that his own teaching, that of Shankara and Dakshinamurthi are one.

In spite of the seemingly complex history of nondualistic thought, the Ramanasramam, home of contemporary Advaita, is easy and relaxed. There are the Westerners in their orange T-shirts and white cotton trousers, Indian men in their dhotis and kurta pyjamas and Indian women in their brightly-coloured saris, looking like reincarnations of Hindu goddesses. Everyone glides about wrapped in a state of serene peace. What a blessed life it would be to exist just like this, I think—reading, writing and contemplating the teachings of the wise. How difficult it is to find tranquillity in the midst of daily activities whilst living in the West. How the din and the noise of urban life appear to be such an obstacle to finding one’s true Self.

At eleven, there is the feeding of the poor in the ashram. The Doctor presides over large bowls of rice and vegetable curry, as the courtyard by the main entrance fills up with every example of human life. It is a moving sight to behold—sadhus, beggars, the disabled and dispossessed, form a loose queue for their daily food offering. Thin, skeletal bodies, daubed in holy ash, their orange robes and mala beads, dreadlocks and matted beards, making them indistinguishable from one another. But their beady eyes and gracious acceptance of what is given make me feel humbled by their example.

I wander around the other rooms of the ashram complex. Adjacent to the Main Hall is the Shrine of the Mother, Sri Ramana’s mother, Alagammal. Her body is also entombed in honour of her own apotheosis on 19th May 1922. The room is small with a central shrine, around which I make a turn, noticing the many statues of Ganesh and Siva, festooned with flower petals and dressed in beautiful fabric, making them look like children’s dolls.

Leading from this room and running parallel to the Main Hall is the New Hall. Built in 1949, it is where Ramana gave satsang during his illness in the year before his death so that it could accommodate all the people who had come to see him and wish him well. I much prefer this room—it is far less ostentatious, being decorated only with grey stone carvings and pillars. On the stone floor are mandalas and yantra etched onto the floor in white chalk. There is also another ebony-coloured statue of Ramana, surrounded by railings, and on the wall is an old Victorian-style clock, more reminiscent of one you would find in a British railway station rather than an Indian ashram.

Photograph: © Ramanasramam

Then I notice a large white board, more than 10 feet high, propped up against the left sidewall. “Death Experience of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi” it reads in large black letters. I stand transfixed by the text written out before me:

It was about six weeks before I left Madura for good that the great change in my life took place. It was quite sudden. I was sitting alone in a room on the first floor of my uncle’s house. I seldom had any sickness, and on that day there was nothing wrong with my health, but a sudden violent fear of death overtook me. There was nothing in my state of health to account for it and I did not try to account for it or to find out whether there was any reason for the fear. I just felt ‘I am going to die’ and began thinking what to do about it. It did not occur to me to consult a doctor or my elders or friends; I felt that I had to solve the problem myself, there and then.

The shock of the fear of death drove my mind inwards and I said to myself mentally, without actually framing the words: ‘Now death has come; what does it mean? What is it that is dying? This body dies.’ And I at once dramatized the occurrence of death, I lay with my limbs stretched out stiff as though rigor mortis had set in and imitated a corpse. So as to give greater reality to the enquiry, I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed so that no sound could escape, so that neither the word ‘I’ nor any other word could be uttered.

‘Well then,’ I said to myself, ‘this body is dead. It will be carried stiff to the burning ground and there burnt and reduced to ashes. But with the death of this body, am I dead? Is the body ‘I’? It is silent and inert but I feel the full force of my personality and even the voice of the ‘I’ within me, apart from it. So I am Spirit transcending the body. The body dies but the Spirit that transcends it cannot be touched by death. That means I am deathless Spirit.’

All this was not dull thought; it flashed through me vividly as living truth which I perceived directly, almost without thought-process. ‘I’ was something very real, the only real thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity connected with my body was centred on that ‘I’. From that moment onwards the ‘I’ or Self focussed attention on itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of death had vanished once and for all.

Absorption in the Self continued unbroken from that time on. Other thoughts might come and go like the various notes of music, but the ‘I’ continued like the fundamental sruti note that underlies and blends with all the other notes. Whether the body was engaged in talking, reading or anything else, I was still centred on ‘I’. Previous to that crisis, I had no clear perception of my Self and was not consciously attracted to it. I felt no perceptible or direct interest in it, much less any inclination to dwell permanently in it.

This is the final barrier to Self-realization, I think—the fear of bodily death. This is the source of all my latent anxieties, all my worries and concerns. This is what my life has been constructed to avoid dealing with, in some way trying to make death an option, or at least something to deal with only when I am good and ready. But everyone has told me—in the facing of that fear, I will indeed die but it won’t be the type of death I am afraid of. It will be the ultimate death, the extinction of my sense of individuality, the death of the idea that “I am the doer”. Only this, paradoxically, will lead to life beyond death, a life of freedom from fear, a life of blessed immortality and everlasting peace.

In the afternoon, readings are made in this room from Ramana’s teachings. A learned-looking Indian man squats on the floor in front of a large book, from which he sings out a line in Tamil, followed by an English translation. I can barely make out what he is saying in either language but the melodious cadences are a joy to listen to. I then decide to leave and walk over to a small hut opposite the Main Hall. It is where Ramana slept while he gave satsang in the New Hall during his illness and where he finally died: “The place where Sri Bhagavan attained maha nirvana” it reads on a black plaque with gold lettering above the glass doors. Inside is a small collection of Ramana’s things—his walking stick and timepieces as well as metal dishes and pots.

Still meandering around the ashram, I find the bookshop, next to the office. Many people have written about Sri Ramana Maharshi—the first and foremost being Paul Brunton, then a journalist, whose book, A Search in Secret India, made Ramana’s teachings popular in the West. Others include Arthur Osborne, Major Chadwick and S. S. Cohen, W. Somerset Maugham and C. G. Jung. More recently, David Godman, who still lives in Tiruvannamalai, has made accessible the teachings of Ramana by not only editing The Mountain Path, the journal of the Ramanasramam, but also by collating his teachings into one easily manageable book, Be As You Are: The Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi.

The shop is filled with shelf upon shelf of Bhagavan’s teachings and biographies, translated into most of the world languages. I have a specific list of titles that I wish to purchase and buy Talks, Day by Day with Bhagavan and Letters from Sri Ramanasramam as well as two biographies by B. V. Narasimha Swami and Arthur Osborne. I then return to my room to look at them all.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

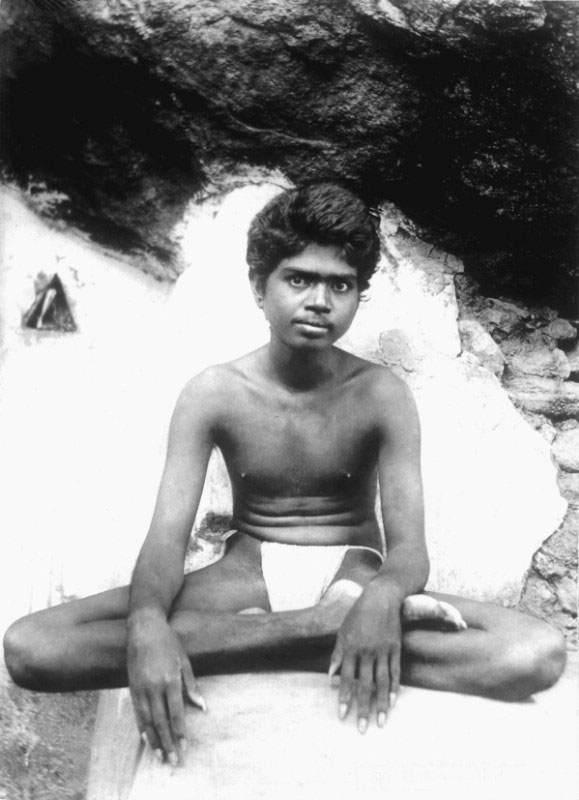

It was in 1895 that two significant events unfolded in the life of the young boy, sparking the flame of desire for Self-knowledge, the answer to the question, Who am I? An elderly relative came to visit the family and Venkataraman, asking where he had been, was told that the relative had just returned from Arunachala. The name of the hill had a deep effect on the boy, its sound evoking a longing for something mysterious and magical. Similarly, it was also around this time that Venkataraman discovered a copy of Periapuranam, a book describing the lives of 63 Tamil saints and their love for God. So inspired was he by the work and hearing the sacred word, Arunachala, that it precipitated a spiritual crisis when Venkatraman was only 17. The internal monologue Venkataraman subsequently held within himself as he was taken over by an intense fear of death has become such a famous spiritual soliloquy that it now has pride of place in the ashram.

And indeed, if even the very act of turning towards God is part of one’s destiny, then this event in Venkataraman’s life was as it should have been. For a curse had been placed on the family that every generation would produce an ascetic. A wandering monk had once visited the house but was not given due respect and, upon leaving, he declared that each generation of Venkataraman’s family would produce one member who would become a monk, having to wander in search of food. It would appear that the omen had come true.

Venkataraman continued to live in the house but was rebuked by his uncle and brother for behaving like a sadhu whilst enjoying the comforts of a householder. Thus, on 29th August 1896, while copying out English grammar for homework, his soul rebelled against the seemingly pointless exercise. He thus decided to leave his home and go to Arunachala for good. He wrote a short note, explaining his decision: “I have, in search of my father and in obedience to his command, started from here. This is only embarking on a virtuous enterprise. Therefore none need grieve over this affair …” He arrived in Tiruvannamalai on 1st September 1896.

The first place of residence for Venkataraman was in the thousand-pillared hall or mantapam of the Temple of Arunachaleswara in Tiruvannamalai. He shaved his head, tore his clothes to shreds, wore only a loincloth and threw all his money away. He then took a vow of silence, thus becoming a mouni. The young “Brahmana Swami”, as he was now referred to, attracted a lot of attention, both reverential and mischievous but he was always protected and fed by pious locals. Indeed, he was to spend many, many years living in various temples and caves on and around Arunachala, always under the protective guise of a devotee. Virupaksha Cave was always his chief residence, however; shaped like the sacred mantra Om, it contains the remains of Saint Virpakshadeva and thus, was a fitting residence for the Swami.

In 1907, a learned scholar and poet called Ganapati Sastri came and visited Brahmana Swami to ask him what was the true nature of tapas (spiritual practice). The Swami told him, “If one watches whence this notion ‘I’ springs, the mind is absorbed into that. That is tapas.” Upon hearing these words, Ganapati Sastri’s heart was so filled with joy that he composed five stanzas in praise of the Swami, wherein he contracted the Swami’s name, Venkataraman, into Ramana. In a letter he also wrote the following day to relatives and disciples, he said that the Swami deserved the title “Bhagavan Maharshi” meaning “Lord, the Great Rishi” since he had never heard such depth of understanding as this before. Thus, the name Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi became the adopted name for Venkataraman Brahmana Swami.

It was not until November 1922 that Ramana took up residence at the foot of the hill in what is now known as the Ramanasramam. Initially, the ashram was only a small collection of thatched huts and hermitages but it has grown into a sizeable compound of stone buildings, marble halls and shrines. Indeed, as a devotee, it is still possible to stay in the ashram but you need to give at least three months’ notice, such is the demand.

Up until his death, Ramana never left Arunachala, remaining in the ashram and receiving devotees from all walks of life. He led a simple life—he would rise between three and four in the morning, listen to chants in praise of Bhagavan or Arunachala and then greet visitors who had come to sit with him. He would occasionally help with the ashram chores, such as chopping vegetables, cutting and polishing walking sticks, stitching leaf-plates and binding notebooks but he would always take an afternoon stroll on the hillside. In the evening there would be meditation and the recitations of devotees, followed by dinner. The day would come to a close at around nine.

At the beginning of 1949, a small nodule appeared below Ramana’s left elbow. In February, the ashram doctor removed the lump but within a month it returned, much larger and more painful than before. Diagnosed as a sarcoma, it was operated on but the wound did not heal, resulting in another growth appearing higher up the arm. Doctors feared that Ramana was in great pain but he always dismissed their concern: “There is pain,” he would admit, “but what has that to do with me?” He would also add, “You attach too much importance to the body.”

On 4th December he was unsuccessfully operated on for the final time. Devotees, in the growing realization that Bhagavan was nearing the end of his life, asked what they would do without him, to which he replied: “They say that I am dying but I am not going away. Where could I go?” By January the following year, he was too weak to remain in the New Hall and was moved to the small ante-room opposite. Finally, on 14th April 1950, when his body was wracked with physical pain and disease, devotees started to gather in the courtyard chanting Arunachala Siva, sensing that the end of Bhagavan’s life was drawing near. Upon hearing the music, Ramana smiled, tears of bliss streamed from his eyes and he drew his last breath. His maha samadhi was at 8:47 pm. And, at exactly the same moment, a large star was seen to trail slowly across the sky towards the peak of Arunachala.

[Extract: Paula Marvelly, The Teachers of One: Conversations on the Nature of Nonduality]

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Post Notes

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Saint

- Alan Jacobs: Who Am I?

- Ana Ramana: Hymns to the Beloved

- Upahar: Bright Like a Million Suns

- Paula Marvelly: A Singular Man