Philosophies of Art

“… in the conscience of the artist, the Truth of Art is foremost.”

“I’M INTERESTED ONLY in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on,” declared Latvian-born, Jewish-American Abstract Expressionist painter, Mark Rothko (25th September 1903–25th February 1970), “and the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions … If you … are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point.”

Despite the fact that the impetus of his paintings needed no defining explanation other than their very own existence, Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz had been privately crafting his own philosophical reflections on the nature of art and the state of the human condition. Brilliantly edited by his son, Christopher, and only published after Rothko’s death, The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art is a collection of revelatory essays delving deep into the painter’s personal beliefs on the nature of beauty, reality, myth, plasticity, space, sensuality, the Renaissance and the role of unconscious processes in creative work.

Composed in the early 1940s, the manuscript was written long before the production of his abstract “colour field” compositions of richly painted squares decades later, as well as the iconic Rothko Chapel Paintings shortly before his suicide. Nevertheless, the metaphysical and mythological elements of his remarkable artistic output find their genesis in this visionary offering, not least his ode to the life of the creative, “The Artist’s Dilemma”, in which he expounds the age-old debate of achieving artistic perfection— “the sublime” —in the face of distraction and compromise.

Mark Rothko, No. 6 (Yellow, White, Blue Over Yellow on Grey).

Image: Fair Use

What is the popular conception of the artist? Gather a thousand descriptions, and the resulting composite is the portrait of a moron: he is held to be childish, irresponsible, and ignorant or stupid in everyday affairs.

The picture does not necessarily involve censure or unkindness. These deficiencies are attributed to the intensity of the artist’s preoccupation with his particular kind of fantasy and to the unworldly nature of the fantastic itself. The bantering tolerance granted to the absentminded professor is extended to the artist […]

This myth, like all myths, has many reasonable foundations. First, it attests to the common belief in the laws of compensation: that one sense will gain in sensitivity by the deficiency in another. Homer was blind, and Beethoven deaf. Too bad for them, but fortunate for us in the increased vividness of their art. But more importantly, it attests to the persistent belief in the irrational quality of inspiration, finding between the innocence of childhood and the derangements of madness that true insight which is not accorded to normal man. When thinking of the artist, the world still adheres to Plato’s view, expressed in Ion in reference to the poet: ‘There is no invention in him until he has been inspired and is out of his senses, and the mind is no longer in him.’ Although science, with scales and yardstick, daily threatens to rend mystery from the imagination, the persistence of this myth is the inadvertent homage which man pays to the penetration of his inner being as it is differentiated from his reasonable experience.

Strange, but the artist has never made a fuss about being denied those estimable virtues other men would not do without: intellectuality, good judgement, a knowledge of the world, and rational conduct. It may be charged that he has even fostered the myth. In his intimate journals, Vollard tells us that Degas feigned deafness to escape disputations and harangues concerning things he considered false and distasteful. If the speaker or subject changed, his hearing immediately improved. We must marvel at his wisdom since he must have only surmised what we know definitely today: that the constant repetition of falsehood is more convincing than the demonstration of truth. It is understandable, then, how the artist might actually cultivate this moronic appearance, this deafness, this inarticulateness, in an effort to evade the million irrelevancies which daily accumulate concerning his work. For, while the authority of the doctor or plumber is never questioned, everyone deems himself a good judge and an adequate arbiter of what a work of art should be and how it should be done.

Let us not delude ourselves with visions of a golden age freed of this cacophony. This gilding is an artistic falsehood. We deal in fantasy ourselves and know how alive dreams can seem. And an age like ours, which demands so clear a facing of realities, will not allow us the pleasure of narcoticism. With the knowledge that man’s tribulations, at least, are always with him, we can safely say that the artist of the past had good reason, too, to play the mad fool—so as to salvage those moments of peace when the demands of the demons could be quieted and art pursued. And if nature, in fact, contrived to give him the appearance of a fool, so much the better. For dissimulation is an exacting art […]

—Mark Rothko, The Artist’s Reality, ‘The Artist’s Dilemma’

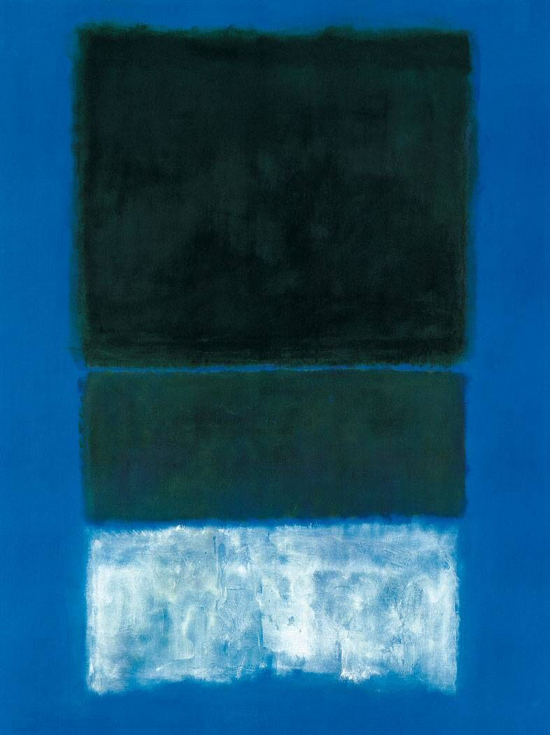

Mark Rothko, No. 14, White and Greens in Blue.

Image: Fair Use

Most societies of the past have insisted that their own particular evaluations of truth and morality be depicted by the artist. Accordingly, the Egyptian artist had to produce a definitely prescribed prototype; the Christian artist had to abide by the tenets of the Second Council of Nicea or be anathematized or, like the monk of the iconoclast age, work in danger and by stealth. We should note that Michelangelo’s nudes were forced to wear, in the end, the appropriate panties and drapes. Authority formulated rules, and the artist complied. We shall not speak here of those whose daring periodically revitalized art, saving it from its narcissistic mimicry of itself. We can accurately say that, within these periods, the artist had to submit to those rules or simulate the appearance of submission, if he were to be permitted to practise his art.

It will be pointed out that the artist’s lot is the same today, that the market, through its denial or affording of the means of sustenance, exerts the same compulsion. Yet there is this vital difference: the civilizations enumerated above had the temporal and spiritual power to summarily enforce their demands. The Fires of Hell, exile, and, in the background, the rack and stake, were correctives if persuasion failed. Today the compulsion is Hunger, and the experience of the last four hundred years has shown us that hunger is not nearly as compelling as the imminence of Hell and Death. Since the passing of the spiritual and temporal patron, the history of art is the history of men, who, for the most part, have preferred huger to compliance, and who have considered the choice worthwhile. And choice it is, for all the tragic disparity between the two alternatives.

The freedom to starve! Ironical indeed. Yet hold your laughter. Do not underestimate the privilege. It is seldom possessed, and dearly won. The denial of this right is no less ironical: think of the condemned criminal who will not eat and who is fed by force, if needs be, until his day of execution. Concerning hunger, as concerning art, society has traditionally been dogmatic. One had to starve legitimately—through famine or blight, through unemployment or exploitation—or not at all. One could no more contrive his own starvation than he could take his own life; and for the artist to have said to society that he would sooner starve than traffic with her wares or tastes would have been heresy and dealt with summarily as such. Within the dogmas of the totalitarian states of today, you may be sure, the artist must starve correctly, just as he must paint by the dictates of the State.

But here, today, we still have the right to choose. It is precisely the possibility of exercising choice wherein our lot differs from that of the artists of the past. For choice implies responsibility to one’s conscience, and, in the conscience of the artist, the Truth of Art is foremost. There may be other loyalties, but for the artist, unless he has been waylaid or distracted, they will be secondary and discarded in his creation of art. This artistic conscience, which is composed of present reason and memory, this morality intrinsic to the generic logic of art itself, is inescapable. Violate her promptings and she will ferret out the deepest recesses of thought and conjecture. Neither sophistries nor rationalizations can quiet her demands […]

Today, instead of one voice, we have dozens issuing demands. There is no longer one truth, no single authority—instead there is a score of would-be masters who would usurp their place. All are full of histories, statistics, proofs, demonstrations, facts and quotations. First they plead and exhort, and finally they resort to intimidation by threats and moral imprecations. Each pulls the artist this way and that, telling him what he must do if he is to fill his belly and save his soul.

For the artist, now, there can be neither compliance nor circumvention. It is the misfortune of free conscience that it cannot be neglectful of means in the pursuit of ends. Ironically enough, compliance would not help, for even if the artists should decide to subvert his conscience, where would he find peace in this Babel? To please one is to antagonize the others. And what security is there in any of these wrangling contenders?

The truths of India, Egypt, Greece spanned over centuries. In matters of art, our society has substituted taste for truth, which she finds more amusing and less of a responsibility, and changes her tastes as frequently as she changes her hats and shoes. And here might the artist, placed between choice and diversity, raise his lamentations louder. Never did his afflictions have as many shapes or such a jabbering of voices, and never did they exude such a prolixity of matter.

—Mark Rothko, The Artist’s Reality, ‘The Artist’s Dilemma’

Post Notes

- Feature image: Mark Rothko, Untitled, Fair Use

- Rothko Chapel

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Paul Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Guy Laramée: Fraîcheur

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Stephen Nachmanovitch: The Art of Is

- Suzanne Moss: Seeking Sanctuary

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme