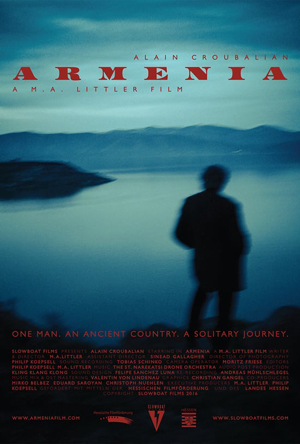

M. A. Littler, Slowboat Films, Armenia

A conversation on writing and filmmaking as conduits to Consciousness

“I think without cultivating the archaic in us we start to internally die.”

—M. A. Littler

M. A. Littler is a German writer, filmmaker and editor of the transatlantic literature and arts magazine, Sargasso. Sven Heuchert is a German novelist. Both share an affinity for the marginalized, the outcast and the nether regions where the intellectual meets the primitive.

In this week’s guest post for The Culturium, Marc and Sven dialogue on the nature of and inspiration behind their work.

Sven Heuchert: MARC, IN YOUR WORK, you always point to spiritual symbols and the worlds of thought that lie behind those symbols—Christian mysticism, Zen, but also archaic elements and the Old Testament. It seems that you often go to the roots, looking for the beginnings, for an original ontology. It is not a shell game with formulas. What interests you in this subject, especially in relation to your artistic work?

M. A. Littler: After almost two decades of writing and making films, I only now fully realize that I am not at all concerned with issues of zeitgeist but primarily with archetypes and themes that have been relevant to our species 3,500 years ago, as well as today, and will be relevant throughout the foreseeable future—you might say classical themes, themes that have stood the test of time.

However, when I began writing, those mythological elements were already present.

Why exactly I do not know, it was simply how the text came out.

I could offer a theory: my father was and is deeply religious and there was a lot of biblical language in the house, a lot of references to Pascal, Meister Eckhart, Calvin and plenty of Job and so the “flavour” of that kind of thought and language was something I simply grew up with.

In my teens, I obsessed about the Beats and that led to D. T. Suzuki, Alan Watts and the Eastern spiritual traditions.

The Western mythological elements are rather hot-blooded in my writing, as you would imagine when exploring the physical and mental innards of man; the Eastern elements create a calmness, a detachedness, and cool things down a notch.

In recent years I have begun to see mythological and archaic/pagan knowledge as a gateway to an inner river of sorts, a river that lies dormant in our so-called modern times.

I think without cultivating the archaic in us we start to internally die.

But speaking of themes and how biographies shape the themes we deal with as writers, Sven, your street realism and noir writings present a bleak, brutal and rather hopeless world. I’m not going to bore you with questions pertaining to your childhood but I am rather interested in something else: do you think the act of writing can have a healing effect, can writing be an antidote to personal pain?

Photograph: © Slowboat Films

Sven Heuchert: Gordon Lish [American writer] said: “Writing is not about self-expression; it is about putting words on paper. The act of writing is not isolated, it is the result of many slow, even painful processes.”

Literature is a distillate.

I believe that everything I write is initially based on a personal foundation.

Then begins the act of composition: an oscillation between the lines often creates text on its own.

The characters begin to speak, their thoughts sharpen, everything gains contrast. In the end, it is an amalgam of the autobiographical and the fictional.

Some texts have been hard on me because of their personal nature.

They can have a paralyzing effect caused by the never-ending confrontation with drastic events.

But literature should be truthfulness, should convey truth, and to do so consistently, one must also go where it hurts.

You say you grew up with the words of your father, who is a devout man.

How can I imagine a conversation during dinner? How did you initially deal with the “big” questions? What influences did it have on you growing up?

M. A. Littler: My father rambles—then and now. Wild and free associations ranging from concentration camps to the proper way to cook lamb, from John Bunyan to the scriptures to the possibility of alien life forms.

In short: the challenge was and is to find the gems amidst an ocean of rather manic monologues.

So an ordinary dinner was lamb curry and my father’s holy fool ramblings.

In response to the question of how that might have influenced me: I never knew a state of being without those “big” questions being omnipresent so I cannot compare.

These existentialist themes were and are as ordinary to me as breathing, eating, reading—and passing water.

That’s also why I am attracted to Zen—I like the ordinariness of it.

A less appealing effect is perhaps my revolt and revulsion to and by the trivial and the banal.

I am utterly incapable of small talk and a rather vicious destroyer of banal conversation—very un-Zen in certain situations.

Sven Heuchert: I think the idea of the “inner river” is very pleasant: do you believe that the zeitgeist and the profane, the fast-paced life of a purely self-reproducing civilization, has led to the demolition of contact with this inner stream?

M. A. Littler: Absolutely.

I have nothing to add to your statement—but I do have a question for you: I often refer to my writing and films as an act of spiritual and intellectual self-defence.

Do you consider your writing an act of revolt? If so, a revolt against who or what?

Photograph: © Slowboat Films

Sven Heuchert: Ad Reinhardt [American abstract painter] said: “The one thing to say about art is that it is one thing. Art is art-as-art and everything else is all else.”

First of all, I write my own chronicle.

My characters keep reoccurring, forever transforming.

They grow with me and change, become larger or smaller, occupy more or less space.

An author never lives entirely—he is always receiving, perceiving, hearing, collecting.

Everything can and will become history under his hands.

My work is revolutionary in so far as that I do not compromise on form and content.

I do not bow to the taste of the masses.

But I do not understand my work as an act of revolution in the sense of a political statement.

There is no political art for me.

The figures in my stories are personified developments, they are products of political and spiritual conditions.

They think, they speak, they act for certain reasons.

It is one of the ideas behind Bourdieu’s habitus.

The revolution must not become another empty formula.

The idea of a coup is always liberating, but it often seems to me to be a simplistic solution.

Everything is present in the work, yet nothing should be subjected to a certain filter.

You mentioned Zen and the Ordinary.

When I travelled to Japan, I noticed how crass and incommensurable this culture is in the Western world.

We often find no words that can say what is actually meant.

Zen, the thought system behind it, has a nihilistic radiance for many Westerners—it is about dissolution, about nothingness.

Not to hold onto anything.

For many, who have grown up in a radical consumer society for which the purely material counts, these goals simply are not comprehensible.

I have been fascinated by the calm, the stringency, the seriousness with which the great questions are addressed.

Everything is reduced to the essentials—eat, shit, sleep, pray. There is much truth in it.

Photograph: © Slowboat Films

M. A. Littler: I don’t come from a non-materialist background per se, although I think it is fair to say that my family was not overly concerned with accumulating more than they needed.

However, materialism was never practical for me.

I always believed wage labour to be temporary slave labour and I do not conform to the logic and rules of any market and thus semi-poverty was a concept and a way of life I accepted early on.

The same applies to my resulting status as an outsider.

So non-materialism was never a spiritual choice of mine but rather a practical one, or the logical result of my decisions and convictions.

I figured if you own nothing, nothing can be taken from you, if you want nothing, you cannot be controlled, and if you don’t expect to win anything, you’ve got nothing to lose.

That’s one reason I have lost my passion for filmmaking.

The financial and logistical restraints stifle any form of true creativity.

In verse writing anything I can think, can exist—and that is simply not the truth for a filmmaker.

Sven, you know I’m an advocator of the abolishment of the traditional concepts of work/employment etc. However, you are not. Explain why.

Sven Heuchert: Wage labour is the devil’s work—if your share Bob Black [American writer and anarchist]’s point of view.

And I do agree.

However, I come from a working-class family that believed in climbing the social ladder, they believed in reputation, in money, and in increased freedom through money.

However, the work is without soul.

It is not mentally challenging.

It’s work that feeds you and nothing more.

I firmly believe that this circle of tristesse and monotony is the reason for many sicknesses such as depression and general fatigue.

Fact is: exploitation is one of the most basic and malicious practices of mankind, and fairer wages are not the solution.

However, man is what man is, and one ought not to dream too much of idealized versions of what man could or ought to be.

When greed gets the best of man, awful things happen.

Capitalism is a form of organization that accepts greed as its basis and has turned greed into an acceptable standard where it is considered normal to penalize the weak.

Man must return to some sort of balance, must return to the inner river that you mentioned.

Photograph: © Slowboat Films

But back to your initial question: work supplies me with clarity and structure.

Without this structure, I would slip into hazardous conditions—mentally and physically.

I think work also has a spiritual component—I think of the farmer who tills the soil.

It is a type of work that is part of the natural cycle of things, a cycle we are removed from today.

Through the division of labour and other effects, we have moved farther and farther away from the meaningfulness of work, so that it has become dull and empty.

It has become a compulsion, which must be rejected and resisted.

Basically, I believe in the old Catholic notion, that one learns about connections and about oneself by the sweat of one’s brow.

You see something grow and flourish.

You build a house, you build a cabin, that is culture but the system, money, the sheer velocity of life, the transience of the modern age has turned true culture into a haze.

M. A. Littler: Sven, if I take my anti-work stance to its logical conclusion, I end up in a grim place—but I am willing to go there.

It might become the natural conclusion to my way of thought and my way of life.

I always reserve the right to say no.

To all things.

Including my own existence.

So, the notion that I might eventually be forced into partaking in any kind of traditional work in order to survive, the notion that there is no refuge from that logic is incorrect.

It is possible to say no to work, to money, to the status quo—even if in all consequence that means saying no to your own survival.

Sven Heuchert: Do you believe in causes? Is there a missionary aspect to your work?

M. A. Littler: A true dialogue is an exchange of ideas and that is nothing less than a manifestation of the generosity of one’s spirit.

I feel we’re lacking that at present.

My writings and films aim to fill that void to a certain extent and to disseminate ideas, not only mine but also those of others.

As such the films and writings are not unlike seeds, what they will grow into I have no idea.

Post Notes

- M. A. Littler’s website

- Slowboat Films

- Sven Heuchert’s website

- Sargasso Magazine

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- M. A. Littler: The Mystic Mind

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates