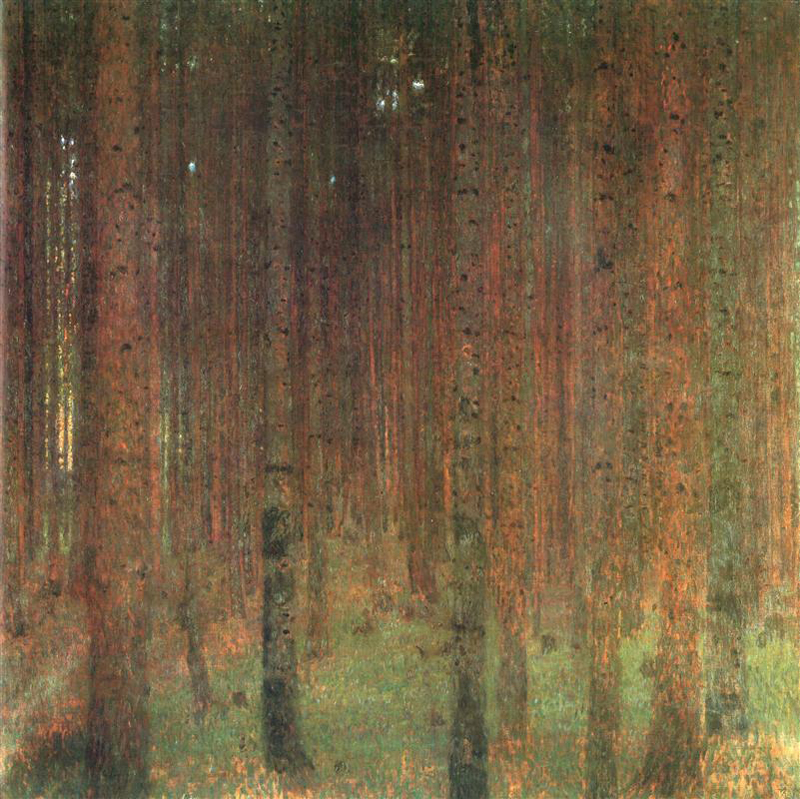

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

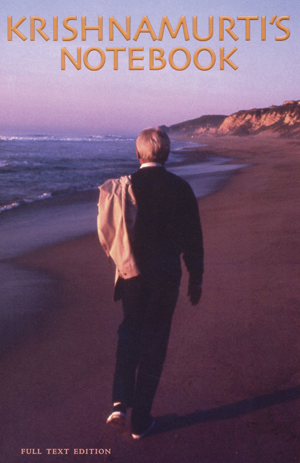

The path to peace

Something strange is happening to the physical organism. One can’t exactly put one’s finger on it but there’s an ‘odd’ insistency, drive; it’s in no way self-created, bred out of imagination. It is palpable when one’s quiet, alone, under a tree or in a room; it is there most urgently as one’s about to go off to sleep. It’s there as this is being written, the pressure and the strain, with its familiar ache.

Formulation and words about all this seem so futile; words however accurate, however clear the description, do not convey the real thing. There’s a great and unutterable beauty in all this. There is only one movement in life, the outer and the inner; this movement is indivisible, though it is divided. Being divided, most follow the outer movement of knowledge, ideas, beliefs, authority, security, prosperity and so on. In reaction to this, one follows the so-called inner life, with its visions, hopes, aspirations, secrecies, conflicts, despairs. As this movement is a reaction, it is in conflict with the outer. So there is contradiction, with its aches, anxieties and escapes.

There is only one movement, which is the outer and the inner. With the understanding of the outer, then the inner movement begins, not in opposition or in contradiction. As conflict is eliminated, the brain, though highly sensitive and alert, becomes quiet. Then only the inner movement has validity and significance. Out of this movement there is a generosity and compassion which is not the outcome of reason and purposeful self-denial. The flower is strong in its beauty as it can be forgotten, set aside or destroyed. The ambitious do not know beauty. The feeling of essence is beauty.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 27th June 1961, Ojai

MUCH HAS BEEN written about the early life of Jiddu Krishnamurti (1st May 1895–17th February 1986) and how, in his early teens, he was discovered on a beach on the Adyar river and “adopted” by the Theosophical Society to be the vehicle for the return of the Lord Maitreya. At the age of 26, however, he had a profound spiritual awakening, lasting initially for three days comprising a sharp pain in the nape of his neck, increasing in intensity with loss of appetite and occasional delirious ramblings, and eventually climaxing in a state of mystical union and immeasurable inner ease.

The symptoms, nonetheless, continued to afflict him throughout the rest of his life, albeit in a milder manner, which he simply alluded to as “the process”. Profoundly affected by his personal experience, he came to the realization that individual insight, and not collective conditioning, was the only viable way to become free. He subsequently renounced his formal training to become the “World Teacher” and instead, set out to walk alone into the pathless land of all things timeless, wise and beautiful.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

Woke up early with that strong feeling of otherness, of another world that is beyond all thought; it was very intense and as clear and pure as the early morning, cloudless sky. Imagination and illusion are purged from the mind for there is no continuance. Everything is and it has never been before. Where there is a possibility of continuance, there is delusion. It was a clear morning though soon clouds would be gathering. As one looked out of the window, the trees, the fields were very clear. A curious thing is happening; there is a heightening of sensitivity. Sensitivity, not only to beauty but also to all other things. The blade of grass was astonishingly green; that one blade of grass contained the whole spectrum of colour; it was intense, dazzling and such a small thing, so easy to destroy. Those trees were all of life, their height and their depth; the lines of those sweeping hills and the solitary trees were the expression of all time and space; and the mountains against the pale sky were beyond all the gods of man. It was incredible to see, feel, all this by just looking out of the window. One’s eyes were cleansed.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 3rd August 1961, Gstaad

I was first alerted to Krishnamurti’s Notebook in a video by Eckhart Tolle. Like so many travellers upon the solitary journey, the words of the great Indian teacher had formed the very bedrock of my spiritual practice over the years. And yet, most of the texts I have accumulated are edited transcripts of his talks so I was amazed to discover that this collection of journal entries was in fact compiled by Krishnamurti firsthand.

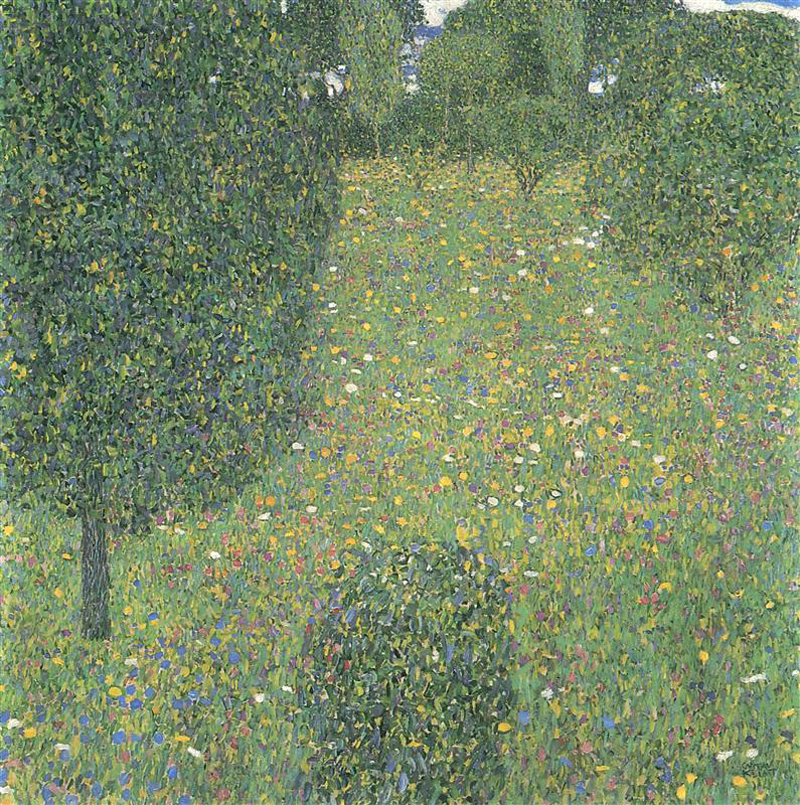

Started in June 1961 in New York whilst staying with friends and not originally intended for publication, he would keep a daily record over the course of the next seven months (save for fourteen days) during his time spent travelling through America, England, Italy, the Alps and India, outlining his perceptions and state of consciousness in specific response to the overwhelming beauty of the natural world. Often speaking directly of “the process” and its painful effects on the body, he would also recollect moments of unbounded awareness and mystical states, described interchangeably as “the benediction”, “the immensity”, “the sacredness” and “the otherness”, in which the flora and fauna surrounding him would become the very embodiment of the divine.

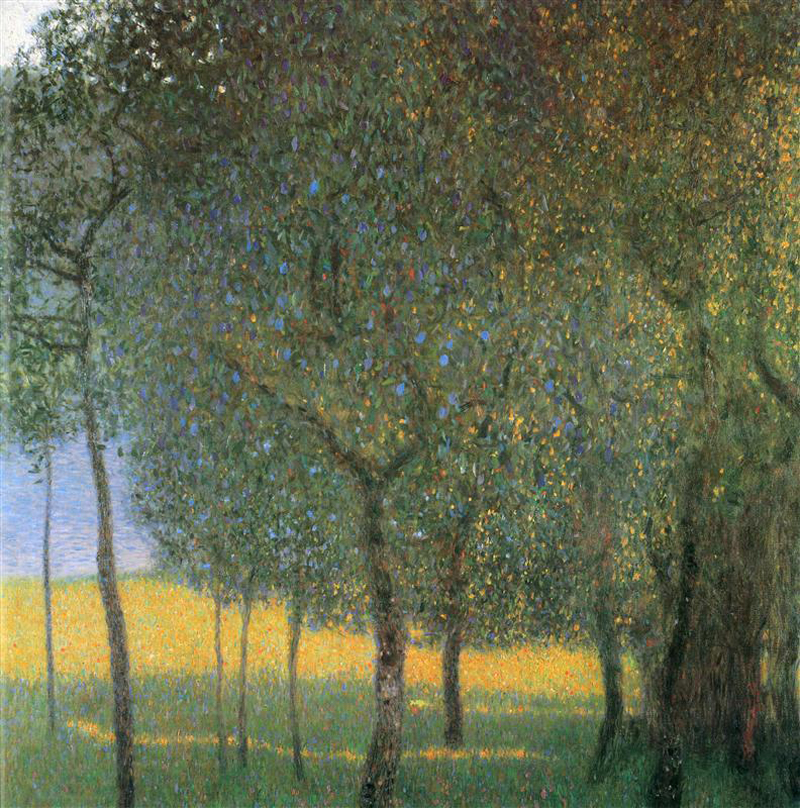

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

There was a beautifully kept lawn, not too large and it was incredibly green; it was behind an iron grille, well watered, carefully looked after, rolled and splendidly alive, sparkling in its beauty. It must have been many hundred years old; not even a chair was on it, isolated and guarded by a high and narrow railing. At the end of the lawn, was a single rose bush, with a single red rose in full bloom. It was a miracle, the soft lawn and the single rose; they were there apart from the whole world of noise, chaos and misery; though man had put them there, they were the most beautiful things, far beyond the museums, towers and the graceful line of bridges. They were splendid in their splendid aloofness. They were what they were, grass and flower and nothing else. There was great beauty and quietness about them and the dignity of purity. It was a hot afternoon, with no breeze and the smell of exhaust of so many cars was in the air but there the grass had a smell of its own and one could almost smell the perfume of the solitary rose.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 24th September 1962, Paris

Jiddu Krishnamurti famously avocated that truth cannot be attained through any organization, creed or dogma, nor through any philosophical knowledge or psychological technique. The only way, he believed, was not simply by understanding the contents of one’s own mind but also through the mirror of relationship with, and in observation of, daily life. His Notebook is the culmination of this quest. Exquisitely composed in some of the most lyrically sublime language of any spiritual literature I have ever engaged with, his graceful prose has the effect of transporting us unto a realm of being, paradoxically, beyond all thought and word.

Moreover, his entire life became an expression of his personal vision; his public talks—in which he would address fundamental questions concerning human conflict, suffering and ignorance as well as perception, beauty and love—would attract hundreds of people from all around the globe. And in the latter part of his life, having put into practical application the tenets of his convictions, he would travel between the schools he had established to disseminate his radical teaching throughout the world, namely in India, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

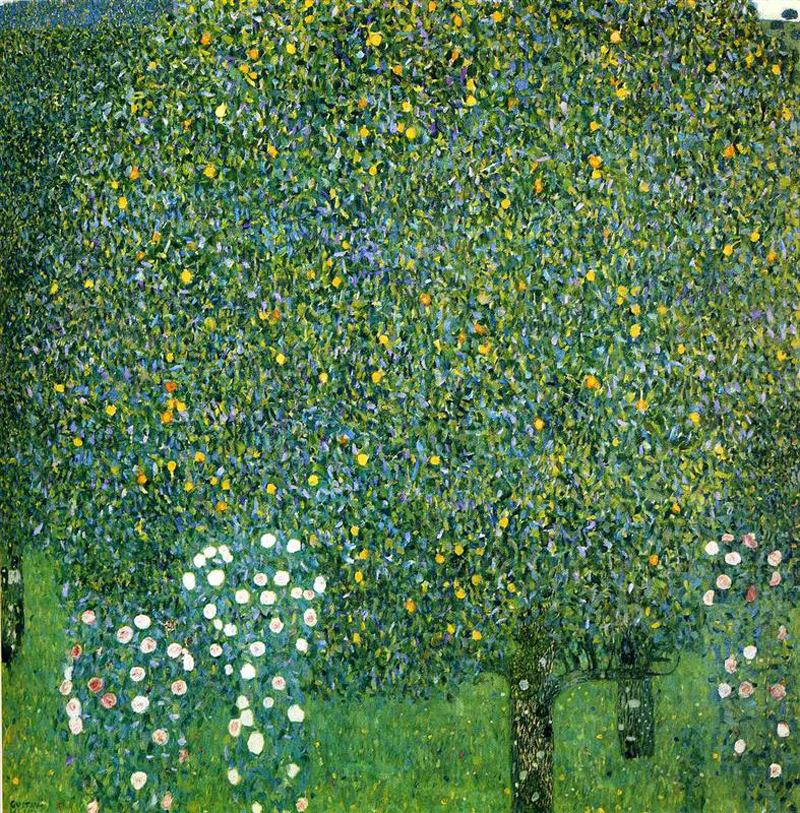

Under the trees it was very quiet; there were so many birds calling, singing, chattering, endlessly restless. The branches were huge, beautifully shaped, polished, smooth and it was quite startling to see them and they had a sweep and a grace that brought tears to the eyes and made you wonder at the things of the earth. The earth had nothing more beautiful than the tree and when it died it would still be beautiful; every branch naked, open to the sky, bleached by the sun and there would be birds resting upon its nakedness. There would be shelter for owls, there in that deep hollow, and the bright, screeching parrots would nest high up in the hole of that branch; woodpeckers would come, with their red-crested feathers sticking straight out of their heads, to drive in a few holes; of course there would be those striped squirrels, racing about the branches, ever complaining about something and always curious; right on the top-most branch, there would be a white and red eagle surveying the land with dignity and alone. There would be many ants, red and black, scurrying up the tree and others racing down and their bite would be quite painful.

But now the tree was alive, marvellous, and there was plenty of shade and the blazing sun never touched you; you could sit there by the hour and see and listen to everything that was alive and dead, outside and inside. You cannot see and listen to the outside without wandering on to the inside. Really the outside is the inside and the inside is the outside and it is difficult, almost impossible to separate them. You look at this magnificent tree and you wonder who is watching whom and presently there is no watcher at all. Everything is so intensely alive and there is only life and the watcher is as dead as that leaf. There is no dividing line between the tree, the birds and that man sitting in the shade and the earth that is so abundant.

Virtue is there without thought and so there is order; order is not permanent; it is there only from moment to moment and that immensity comes with the setting sun so casually, so freely welcoming. The birds have become silent for it is getting dark and everything is slowly becoming quiet, ready for the night. The brain, that marvellous, sensitive, alive thing, is utterly still, only watching, listening without a moment of reaction, without recording, without experiencing, only seeing and listening. With that immensity, there is love and destruction and that destruction is unapproachable strength. These are all words, like that dead tree, a symbol of that which was and it never is. It has gone, moved away from the word; the word is dead which would never capture that sweeping nothingness. Only out of that immense emptiness is there love, with its innocency. How can the brain be aware of that love, the brain that is so active, crowded, burdened with knowledge, with experience? Everything must be denied for that to be.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 4th December 1961, Madras

Brockwood Park School and its associated Krishnamurti Centre, situated in the English county of Hampshire, are the home of Jiddu Krishnamurti’s enduring legacy in Europe—the school offering to young children and adolescents the opportunity to develop an inner integrity as an indivdual, founded in understanding, compassion and freedom; the centre providing adults a means to deepen their practice in the actualization of becoming a fully authentic and self-aware human being.

Indeed, in preparation for the construction of the centre, Krishnamurti spoke of the need for a building that exuded simplicity, beauty and quietude, where a collection of all his teachings would be available for study by those who would be deeply committed to their inner enquiry. Moreover, it would not be a place where someone would organize and direct others; rather, a facility for supporting spiritual work undertaken on one’s own.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

It’s a morning without a cloud; the sun seems to have banished every cloud from sight. It is peaceful except for the roar of traffic, even though it is Sunday. The pigeons are warming themselves on the zinc roofs and are almost the same colour as the roof. There’s not a breath of air, though it’s cool and fresh. There’s peace beyond thought and feeling. It’s not the peace of the politician nor the priest nor of the one who seeks it. It is not to be sought. What is sought must already be known and what’s known is never the real. Peace is not to the believer, to the philosopher who specializes in theory. It is not a reaction, a contrary response to violence. It has no opposite; all opposites must cease, the conflict of duality. There’s duality, light and darkness, man and woman and so on but the conflict between the opposites is in no way necessary.

Conflict between the opposites arises only when there’s need, the compulsion to fulfil, the need for sex, the psychological demand for security. Then only is there conflict between the opposites; the escape from the opposites, attachment and detachment, is the search for peace through church and law. Law can and does give superficial order; the peace that church and temple offer is fancy, a myth to which a confused mind can escape. But this is not peace. The symbol, the word must be destroyed, not destroyed in order to have peace but they must be shattered for they are an impediment to understanding. Peace is not for sale, a commodity of exchange. Conflict, in every form, must cease and then perhaps it is there. There must be total negation, the cessation of demand and need; then only does conflict come to an end. In emptiness there is birth. All the inward structure of resistance and security must die away; then only is there emptiness. Only in this emptiness is there peace whose virtue has no value nor profit.

It was there early in the morning, it came with the sun in a clear, opaque sky; it was a marvellous thing full of beauty, a benediction that asked nothing, no sacrifice, no disciple, no virtue, no midnight hour. It was there in abundance and only an abundant mind and heart could receive it. It was beyond all measure.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 10th September 1961, Paris

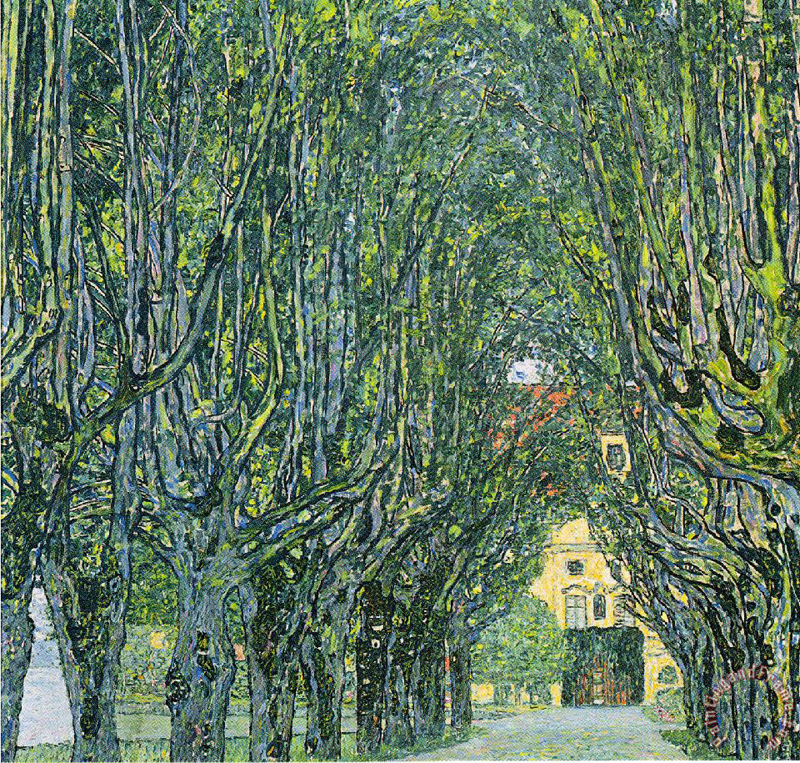

Continuing my exploration of the spiritual inheritance of the south-east of England after my trips to the Berwich Church murals and Cittaviveka monastery, I decide to drive to Brockwood Park in order to steep yet again in the otherness of life. En route, I completely lose all sense of direction, owing to taking a wrong turn, and end up in a single-track lane leading through lush green fields, deep in the Hampshire countryside. In time, I will learn that I am only literally a few kilometres away from my destination but the detour into the uncharted solitude of nature renders me completely disoriented, seemingly foreshadowing a passage into something mysterious and yet familiar.

Despite this, I berate myself for losing the way and yet, miraculously, arrive with many minutes to spare. As I wait in my car for the body’s surging sensations to dissipate, I feel embraced by the scenery around me comprising dense, viridescent shrubs and woodland, with all agitation soon soothed away. A simple path leads through the foliage as I systematically shed all attachments to my past and I step into another world—one of serene beauty, architectural harmony and inexplicable peace.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

Everywhere there was silence; the hills were motionless, the trees were still and the riverbeds empty; the birds had found shelter for the night and everything was still, even the village dogs. It had rained and the clouds were motionless. Silence grew and became intense, wider and deeper. What was outside was now inside; the brain which had listened to the silence of the hills, fields and groves was itself now silent; it no longer listened to itself; it had gone through that and had become quiet, naturally, without any enforcement. It was still ready to stir itself on the instant. It was still, deep within itself; like a bird that folds its wings, it had folded upon itself; it was not asleep nor lazy, but in folding upon itself, it had entered into depths which were beyond itself. The brain is essentially superficial; its activities are superficial, almost mechanical; its activities and responses are immediate, though this immediacy is translated in terms of the future. Its thoughts and feelings are on the surface, though it may think and feel far into the future and way back into the past. All experience and memory are deep only to the extent of their own limited capacity but the brain being still and turning upon itself, it was no longer experiencing outwardly or inwardly.

Consciousness, the fragments of many experiences, compulsions, fears, hopes and despairs of the past and the future, the contradictions of the race and its own self-centred activities, was absent; it was not there. The entire being was utterly still and as it became intense, it was not more or less; it was intense, there was an entering into a depth or a depth which came into being which thought, feeling, consciousness could not enter into. It was a dimension which the brain could not capture or understand. And there was no observer, witnessing this depth. Every part of one’s whole being was alert, sensitive but intensely still. This new, this depth was expanding, exploding, going away, developing in its own explosions but out of time and beyond time and space.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 30th October 1961, Bombay & Rishi Valley

Light suffuses every room—lounge, dining area, library—through large lattice windows, bathing the present moment in a golden lucidity as if the building itself is beyond form. Designed by Keith Critchlow, one of the foremost architects of sacred geometry, the Krishnamurti Centre is constructed around a Quiet Room, which forms the very hub of the building, from which all other rooms spiral like the petals of a lotus flower. Indeed, Critchlow dreamed of a person seated cross-legged in meditation, a concept upon which he based his composition, thus imbuing the space with a still and silent majesty and in utter harmony with the very superstructure of the universe.

I step out onto the lawn and embrace the spring air. I cross over a stile and walk through a flock of docile sheep, unto the woods beyond, Brockwood Park School standing imposingly in the middle distance. A painterly landscape of fields and flowers and trees unfolds before me as I try and remember Krishnamurti’s endorsement to accept everything as it is. I sit down on a log, breathing in the sylvan scents and smells about me. A wood pigeon coos in time with the beats of my innermost heart.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

The sky was burning with fantastic colour, great splashes of incredible fire; the southern sky was aflame with clouds of exploding colour and each cloud was more intensely furious than the other. The sun had set behind the sphinx-shaped hill but there was no colour there, it was dull, without the serenity of a beautiful evening. But the east and the south held all the grandeur of a fading day. To the east it was blue, the blue of a morning-glory, a flower so delicate that to touch it is to break the delicate, transparent petals; it was the intense blue with incredible light of pale green, violet and the sharpness of white; it was sending out, from east to west, rays of this fantastic blue right across the sky. And the south was now the home of vast fires that could never be put out. Across the rich green of rice fields was a stretch of sugar cane in flower; it was feathery, pale violet, the tender light beige of a mourning dove; it stretched over and across the luscious green rice fields with the evening light through it to the hills, which were almost the same colour as the sugar-cane flower.

The hills were in league with the flower, the red earth and the darkening sky, and that evening the hills were shouting with joy for it was an evening of their delight. The stars were coming out and presently there was not a cloud and every star shone with astonishing brilliance in a rain-washed sky. And early this morning, with dawn far away, Orion held the sky and the hills were silent. Only across the valley, the hoot of a deep-throated owl was answered by a light-throated one, at a higher pitch; in the clear still air their voices carried far and they were coming nearer until they seemed quiet among a clump of trees; then they rhythmically kept calling to each other, one at a lower note than the other till a man called and a dog barked …

It was meditation in emptiness, a void that had no border. Thought could not follow; it had been left where time begins, nor was there feeling to distort love. This was emptiness without space. The brain was in no way participating in this meditation; it was completely still and in that stillness going within itself and out of itself but in no way sharing with this vast emptiness. The totality of the mind was receiving or perceiving or being aware of what was taking place and yet it was not outside of itself, something extraneous, something foreign. Thought is an impediment to meditation but only through meditation can this impediment be dissolved. For thought dissipates energy and the essence of energy is freedom from thought and feeling.

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 1st November 1961, Bombay & Rishi Valley

Before I leave, I decide to take a turn down the lane outside the centre and around the surrounding fields. It is the same circuit Krishnamurti would take every afternoon during his sojourns at Brockwood, lasting just under half an hour. I set off, the road dipping slightly down and then bearing towards to the left, subsequently unfolding at a mild incline until once again bending off in an anticlockwise direction.

I try and imagine I am Krishnamurti, walking graciously and effortlessly, every step a sacred act. I pass copses carpeted with bluebells and in the distance, I can see a field of rape. The contrast of violet and yellow makes my heart ache. I stand still and let beauty obliterate me, utterly and completely, as I merge with this rootless, causeless state of being, bringing me unto the blessedness of the present moment and the innate knowing that I am eternally free.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Gustav Klimt Museum

There is something curiously pleasant to walk, alone, along a path, deep in the country, which has been used for several thousand years by pilgrims; there are very old trees along it, tamarind and mango, and it passes through several villages. It passes between green fields of wheat; it is soft underfoot, fine, dry powder, and it must become heavy clay in the wet season; the soft, fine earth gets into your feet, into your nose and eyes, not too much. There are ancient wells and temples and withering gods. The land is flat, flat as the palm of the hand, stretching to the horizon, if there is a horizon. The path has so many turns, in a few minutes it faces in all the directions of a compass. The sky seems to follow that path which is open and friendly. There are few paths like that in the world though each has its own charm and beauty …

But now, this path was not like any other; it was dusty, made foul by human beings here and there, and there were ruined old temples with their images; a large bull was having its fill among the growing grain, unmolested; there were monkeys too and parrots, the light of the skies. It was the path of a thousand humans for many thousand years. As you walked on it, you were lost; you walked without a single thought and there was the incredible sky and the trees with heavy foliage and birds. There is a mango on that path that is superb; it has so many leaves that the branches cannot be seen and it is so old.

As you walk on, there is no feeling at all; thought too has gone but there is beauty. It fills the earth and the sky, every leaf and blade of withering grass. It is there covering everything and you are of it. You are not made to feel all this but it is there and because you are not, it is there, without a word, without a movement. You walk back in silence and fading light …

—Krishnamurti’s Notebook, 3rd January 1962, Rajghat, Benares

Brockwood Park: A Symphony by Iwan Brioc, Louise Cook and Alain Joly

Post Notes

- Brockwood Park School

- The Krishnamurti Centre

- Krishnamurti Foundation Trust

- Eckhart Tolle reads two passages from Krishnamurti’s Notebook

- Leah Luong: Jiddu Krishnamurti

- Ajahn Sumedho: The Sound of Silence

- Duncan Grant: Berwick Church

- Rabindranath Tagore: Gitanjali

- Alain Joly: The Dawn Within