Kim Ki-duk, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

A man for all seasons

The Bodhisattva of Compassion,

When he meditated deeply,

Saw the emptiness of all five skandhas

And sundered the bonds that caused him suffering.

—The Heart Sutra

IN A WORLD obsessed with finding significance and validation through being a somebody, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring tells the story of a solitary monk who has found meaning through forsaking the secular realm and diving deep into the very depths of his own soul. And yet, despite his secluded existence, the outside world inevitably comes calling, reminding us that detachment can only ever truly be a state of mind and disposition of heart.

Written and directed by Korean auteur, Kim Ki-duk’s exquisitely beautiful masterpiece filmed at Jusan Pond in North Gyeongsang Province in South Korea portrays the subsequent relationship between a Buddhist renunciate and his young protégé, characters whose names are never relayed. Nevertheless, despite the film’s absence of any specific temporal referencing, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring is a deeply sophisticated meditation on the vagaries of the human condition reflected within the passing seasons of nature.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

Here then,

Form is no other than emptiness,

Emptiness no other than form.

Form is only emptiness,

Emptiness only form.

—The Heart Sutra

Akin to Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte, which explores similar themes associated with the transience of life set against a backdrop of the natural landscape, the stunning alpine topography forms an integral element to this elegiac drama, with each of the five titular segments representing a stage in a man’s life and the associated lessons he must learn.

Despite the minimal use of dialogue, through the use of Buddhist iconography and Aesopian symbols, we become acutely aware of the inherent message of the ancient nondual teachings embodied in the doctrine of the Three Universal Truths—annica (impermanence), dukka (suffering) and anatta (no self)—as they unfold throughout the movie, with the principles of the Four Noble Truths—the causes and cessation of suffering—forming the didactical framework through which the plot evolves.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

Moreover, in a film steeped in visual imagery, the lake itself functions as a metaphor for universal mind, its silent waters the very embodiment of the enlightenment state, with the floating hermitage representative perhaps of the fragile self, drifting silently atop its omnipresent depths.

Similarly, the monastery’s humble rowboat is symbolic of the individual’s journey on the spiritual path. Beautifully painted with images of Guan Yin (the bodhisattva of compassion and mercy) as she extends a hand that holds the lotus-born child, Maitreya, the future Buddha, it is the yana or vehicle by which the young monk is transported to his spiritual destiny, across the ocean of samsara to the mountain shore of liberation and release.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

Feeling, thought and choice,

Consciousness itself,

Are the same as this.

All things are by nature void

They are not born or destroyed

Nor are they stained or pure

Nor do they wax or wane.

—The Heart Sutra

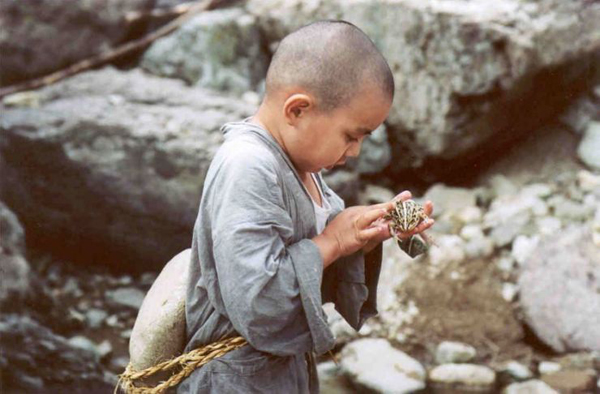

And thus it is springtime. In the manner of a dramatized Eastern fable, the film commences with two wooden carved doors of a “gateless gate” creaking open to reveal a mysterious monastery drifting upon the serene surface of a pond, whose sole occupants are an old monk (Oh Young-soo) and his child disciple (Kim Jong-ho). Life is quiet and simple and like any young boy, the master’s student enjoys playing with his puppy and collecting herbs until one day, he is consumed by the capricious cruelties of childhood.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

After tying pebbles to a fish, a frog and a snake, the young monk later awakens to find that he himself is fettered by a large smooth stone tied to his back. It is the first harsh lesson to be learnt, not through angry chastisement but by redemptive endeavour: the old monk calmly instructs the young boy to release the creatures from their suffering, vowing that if any of the animals die, “You will carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life.”

Indeed, the first Noble Truth—the nature of suffering—is a grave precept to take on board at such an early age, made all the more poignant by the weeping of the boy when he discovers that although the frog has managed to survive, both the fish and snake have perished, signalling a portentous omen of that which is yet to come.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

So, in emptiness, no form,

No feeling, thought or choice,

Nor is there consciousness.

No eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind;

No colour, sound, smell, taste, touch,

Or what the mind takes hold of,

Nor even act of sensing.

—The Heart Sutra

The wooden gates open once again, this time on the season of summer. The young novice is now a teenager (Seo Jae-kyung), moderately adept at keeping the Buddhist rituals of the temple in place. Soon, however, the tranquillity of the hermetic abode is disturbed by the arrival of a young woman, afflicted with an unspecified malady. The master allows her to stay in order to restore her physical and mental strength, noting calmly, “When she finds peace in her soul, her body will return to health.”

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

Needless to say, the young woman awakens sexual desire in the student, with their playful flirtations culminating in passionate lovemaking amidst shoreside rocks and the hull of the master’s rowboat. Upon discovering their secret tryst, the old monk is, however, unmoved and simply observes, “Lust leads to desire for possession, and possession leads to murder,” once again foreshadowing later events. He then dispatches the young woman, now healed, back to her mother. The student is devastated and, forsaking his monastery home, follows after her leaving his eremitic life behind.

The lush and arcadian environment where nature is in its fullest bloom has seeped deep into the soul of the student, stimulating the innate need for consummation and lust. Indeed, the master acknowledges the inevitability of his protégé’s actions by stating wrily it is only natural for him to succumb; without the full realization of the Buddha’s teachings, the cause of our pain and anguish, as the second Noble Truth wisely informs us, is unfettered craving and desire.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

No ignorance or end of it,

Nor all that comes of ignorance;

No withering, no death,

No end of them.

—The Heart Sutra

The wooden threshold now reveals the arrival of autumn. The old monk has considerably aged and yet his modest life is as it always was. Returning from a trip to replenish food supplies, by chance, the master notices devastating news about his former student reported in the local newspaper. Anticipating his imminent arrival, the pupil returns, now a thirty-year-old fugitive (Kim Youg-min), on the run from a violent crime he has recently committed.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

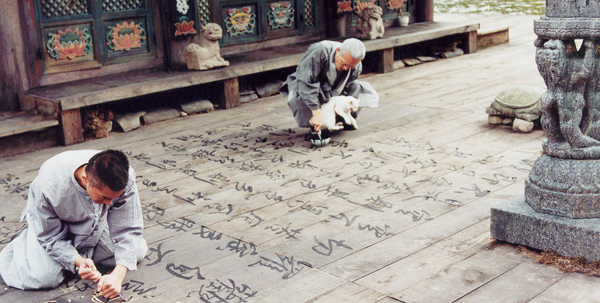

In an act of penance, the student attempts suicide but his master beats him brutally before writing out the Heart Sutra (Prajnaparamitahrdaya or The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom) on the monastery deck, using his cat’s tail as a calligraphy brush. When he finishes, he commands the young monk: “Carve out all of these characters and while you are carving, anger will be cut out of your heart.” As the disciple’s rage dissipates through the painstaking transcription, two policemen arrive to arrest the young monk and carry him away to his fate.

Once again, the old monk is left alone to reflect upon the purpose of life. His duty towards his former student is now completed for he understands that even the pursuit of wisdom itself is rooted in emptiness. He builds a funeral pyre in the rowboat and, covering his ears, eyes, nose and mouth with paper in the manner of the traditional Buddhist death ritual, is engulfed by flames as the boat drifts slowly across the lake, the scene closing with a snake slithering along the hermitage deck.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

Nor is there pain, or cause of pain,

Or cease in pain, or noble path

To lead from pain;

Not even wisdom to attain!

Attainment too is emptiness.

—The Heart Sutra

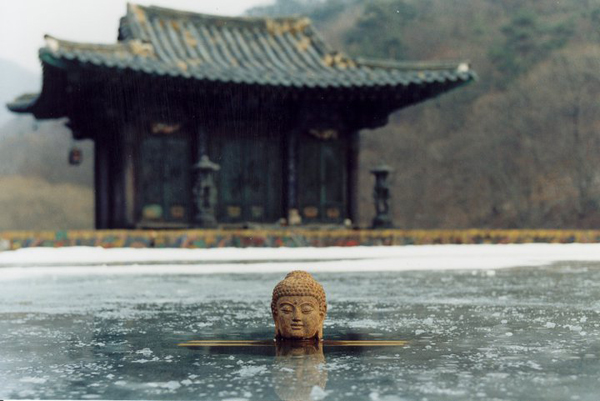

The creaking of the wooden doors now reveals winter has descended upon the secluded monastery, long since abandoned and frozen in ice. Once again, the student returns (as the director himself, Kim Ki-duk), this time on parole as a mature man in middle age. Coming to the realization that his beloved teacher has left the temporal world, he excavates his master’s charred remains from the icy corpse of the rowboat, placing them on the altar, and then embarks upon a new life of prayer, meditation and qigong.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

The monk’s spiritual journey is finally coming to an end as the last two of the Buddha’s Noble Truths are now realized through penance and disciplined adherence to the steps of the Eightfold Path. And thus, in a pilgrimage of atonement for the accumulation of all the suffering in his heart, both unwittingly and wittingly enacted, the monk takes out a statue of Guan Yin, then attaches a millstone to his body with a rope and drags it to the top of a mountain, whereupon he sits in meditation, looking down on his floating hermitage and reflecting upon the unending cycles of human existence.

It is not before long that a veiled woman appears, bearing an infant, whom she entrusts in the care of the monk. Slipping away in the dead of night, the young mother slips on the frozen pond’s surface and falls down a hole, only to be discovered the following morning trapped lifeless under the ice.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

So know that the Bodhisattva

Holding to nothing whatever,

But dwelling in Prajna wisdom,

Is freed of delusive hindrance,

Rid of the fear bred by it,

And reaches clearest Nirvana.

—The Heart Sutra

The wooden threshold opens one final time on a beautiful spring day. The infant is now a young boy and the former student is now master to his new charge. The student is seen tormenting a turtle, harking back to the capriciousness of his predecessor at the beginning of the tale and the egoic seed of attachment and destruction impregnated within in all beings, preparing us yet again for the cycle of life to start anew …

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

Thus the circle of life repeats itself again—nature rejuvenates herself every four seasons, man reincarnates himself through the lifespan of every man and yet everything remains exactly as it was, is, and shall forever be. As the film fades into emptiness, for several moments afterwards we feel the ambient sounds of the natural world—the tinkling of the wind chime, birdsong, the lapping of water against the rowboat—continuing to resonate deep within us, instilling reverence for the sacredness of nature and sublimity of the empty void.

Exquisitely scored and shot with each frame exuding the composition of a painting, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring transmits a transcendental beauty all of its own, elevating the soul with its elegant and timeless aesthetic from innocence, through love and evil, to enlightenment and finally rebirth, subtlely and silently observed by the impassive gaze of a bodhisattva.

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring.

Photograph: © Sony Pictures Classics

All Buddhas of past and present,

Buddhas of future time,

Using this Prajna wisdom,

Come to full and perfect vision.Hear then the great dharani,

The radiant peerless mantra,

The Prajnaparamita

Whose words allay all pain;

Hear and believe its truth!Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate

Bodhi Svaha

Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate

Bodhi Svaha

Gate Gate Paragate Parasamgate

Bodhi Svaha

—The Heart Sutra

Post Notes

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

- Victor Kossakovsky: Gunda + Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier: The Velvet Queen