Photograph: © Éditions du Rocher

Prince of Poets

“Beauty cannot be recognized with a cursory glance.”

—Jean Cocteau

** For bookings to visit Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer, contact:

Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur Tourism Board **

THE FRENCH RIVIERA … Oh, how I yearn to be transported back to the post-war era when the Côte d’Azur exuded an exotic and elegant decadence, inspiring writers—F. Scott Fitzgerald, W. Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene—and painters—Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne—the likes of whom we very rarely encounter in our post-modernist world.

Stepping off the sweltering street in Villefranche-sur-Mer into the Chapelle Saint-Pierre is welcome relief from an atmosphere more enthralled with talk of the Cannes Film Festival and Monaco Grand Prix than the mural legacy of one of France’s greatest artists.

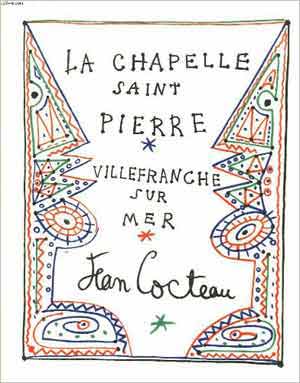

Nestled between chic cafés on Quai Courbet, and very much minding its own business, the ancient Romanesque chapel dedicated to Saint Peter, patron saint of fishermen, was entirely restored and decorated by the “prince of poets”, Jean Cocteau, and has become an outstanding example of the creative fusion between spirituality and art.

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 3.0] Wikimedia Commons

The Russian auteur, Andrei Tarkovsky, wrote in his seminal tract, Sculpting in Time: “… the goal of all art … is to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence […] And so art … is a means of assimilating the world, an instrument for knowing it in the course of man’s journey towards what is called ‘absolute truth’ ….”

French artistic polymath, Jean Cocteau (5th July 1889–11th October 1963), who similarly devoted his entire life to exploring the relationship between the creative imagination and reality, had comparable sentiments about the nature of the beauteousness of art:

Beauty is made up of relationships. It derives its prestige from a specific metaphysical truth, expressed through a host of balances, imbalances, waverings, surges, halts, meanderings, and straight lines, the peculiar quality of which, as a whole, add up to a marvellous number, apparently born without pain. Its distinguishing mark is that it judges those who judge it or imagine that they possess power to do so. Critics have no hold over it. They would have to know the minutest details of how it works and this they cannot do because the mechanics of beauty are secret. Hence the soil of an age is strewn with a litter of cogs that criticism dismantles in the same way as Charlie Chaplin dismantles an alarm clock after opening it like a tin can. Criticism dismantles the cogs. Unable to put them back together or understand the relationships that give them life, it discards them and goes on to something else. And beauty ticks on. Critics cannot hear it because the roar of current events clogs the ears of their souls.

—Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema

Photograph: © Prud’homie des pêcheurs de Villefranche-sur-Mer, Vallée du Var

It takes a few moments for me to shed the dust and din of the outside environment before I can truly steep in the sacred space into which I am now subsumed. Other than the immaculately coiffured woman at the desk by the entrance, my travelling companion and I are the chapel’s only visitors, despite it being Ascension Day and a French public holiday (25th May).

The date is serendipitous, being the day upon which Jesus rose unto heaven following his crucifixion and resurrection, as before me rises up the Christ behind the altar, a simple silhouette in charcoal. Indeed, the overwhelming lucidity and serenity of the chapel momentarily takes my breath away as I stand in awe before the artistry of this beautiful, holy place.

I am considering the immaculate chapel … a gracious dove, the warm and cooing breast of its curves […] I would not dare paint a single line on its feathers, so white and so smooth. Maybe later I will be less timid. The dove will tame me.

—Jean Cocteau

Photograph: © Prud’homie des pêcheurs de Villefranche-sur-Mer, Vallée du Var

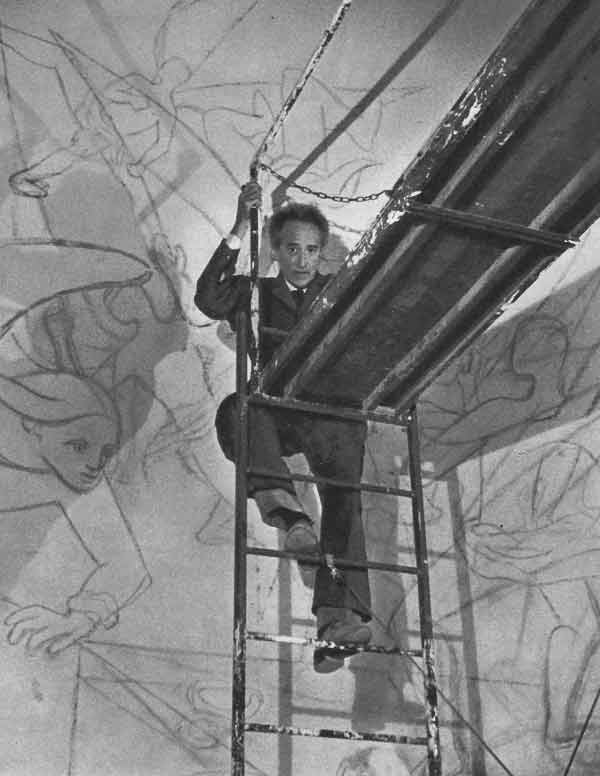

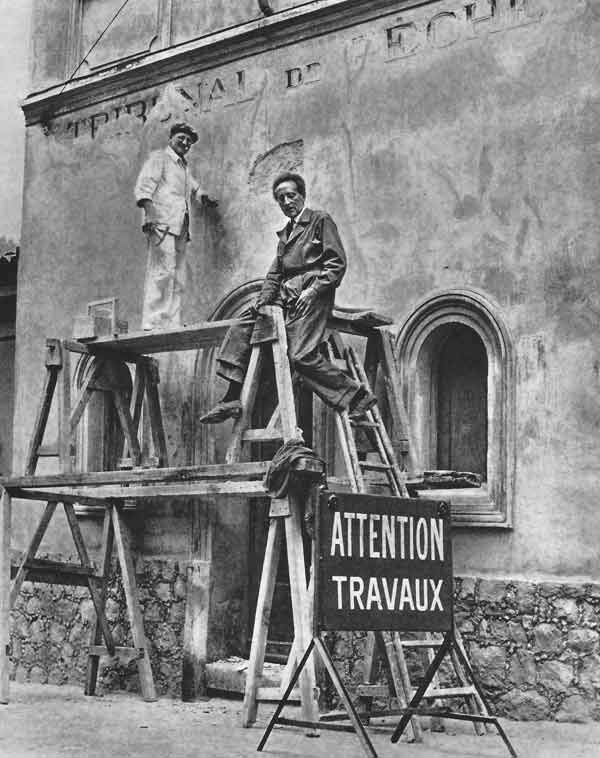

There is no archive of the chapel’s beginning, though Villefranche-sur-Mer itself was founded in 1295. In his diary, Le Passé Défini (The Defined Past), Jean Cocteau wrote that the renovation of the church started on 5th June 1956 with its inauguration on 1st August 1957, though plans for the restoration were always on his mind as far back as the twenties and thirties during the years he lived at the Welcome Hotel on the seafront.

Indeed, rather than being a creative refurbishment of a dilapidated and disused place of worship, Chapelle Saint-Pierre became the manifestation of an artistic vision, embodying in paint and masonry the dreams of a man inspired by the calling of the divine.

Once inside above the entrance door, Jean Cocteau has even immortalized his raison d’être for his conception, should anyone be in any doubt: «Entrez vous-même dans la structure de l’édifice comme étant des pierres vivantes.» [“Introduce yourself in the chapel as one of its living stones.”] Such an evocative invitation was prompted by Saint Peter’s First Epistle:

As you come to him, the living Stone—rejected by humans but chosen by God and precious to him—you also, like living stones, are being built into a spiritual house to be a holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ.

—1 Peter (2:4-5)

Photograph: © Éditions du Rocher

The figure of Christ is drawn on a curve and we are only able to appreciate his greatness as we approach the chancel (le chœur de l’église). At first, Cocteau blamed this subtle optical illusion on a fault in the chapel’s architecture but then confessed later that the phenomenon had been caused by “unknown, creative forces in each of us”, making it a key component of the viewing experience. He would paint approximately fifty faces of the Christ in preparation, taking three days to achieve what he felt was the right expression: “simple, sublime, wise” and even “unpredictable, mocking”.

There are other Biblical parables etched onto the chapel’s walls featuring the life of Saint Peter with almost cartoonesque simplicity—both his Repentance and Liberation—as well as stories of the young girls of Villefranche, gypsies, fishermen and many of Cocteau’s personal friends.

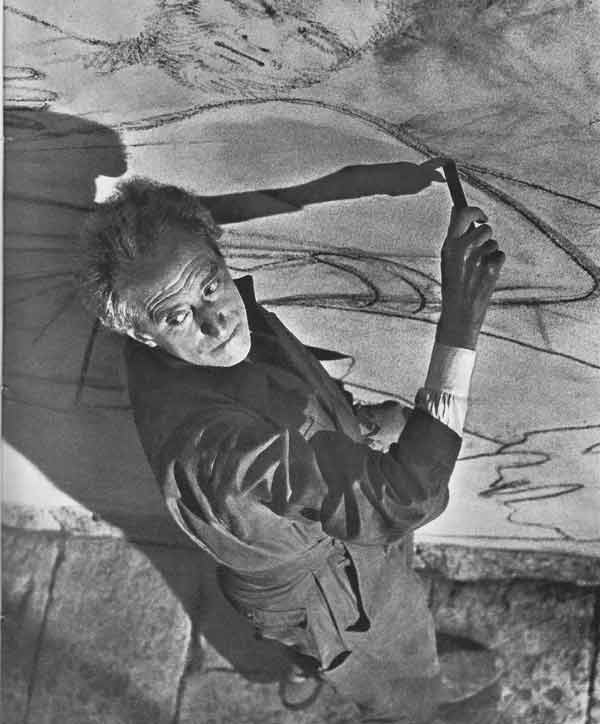

Initially, Cocteau’s drawings were light-projected onto the walls, whereby he would fix the lines in paint and charcoal; thereafter he would add colour here and there with pale pink and white and blue being the dominant hue. The overall effect is one of understated gravitas and grace.

The enormous task that was mine was to nullify myself, avoid imposing myself a style that was not me, let the chapel give its orders and hire me as a middleman.

—Jean Cocteau

Photograph: © Prud’homie des pêcheurs de Villefranche-sur-Mer, Vallée du Var

What fascinates me about Jean Cocteau is the sheer originality and breadth of his creative output. As well as starting the Chapelle Saint-Pierre renovations in 1956, the following year he also commenced shooting Le Testament d’Orphée, the third instalment of his Orphic trilogy—a visually stunning, surrealistic interpretation of the myth of Orpheus, featuring his long-term lover, Jean Marais, and which is an examination of the often torturous relationship between the artist and his work.

I always feel when I gaze upon Cocteau’s compositions a sense that he has given of his very self in their production and we are in touch with the artistic Muse herself; as he said himself, “Poets … shed not only the red blood of their hearts but the white blood of their souls.”

It is relatively easy to dream about a chapel, to think of a setting and pile up drawings and lithographs. It is quite another thing to lock yourself up in a tiny Roman nave, in a dry dock and to wait for its orders.

—Jean Cocteau

Photograph: © Prud’homie des pêcheurs de Villefranche-sur-Mer, Vallée du Var

There is always a lingering sensation of unmitigated calm long after you have seen an artistic creation, which has been imbued with the power of Presence. Its very essence seeps into your cells and transmutes your very soul, as if partaking of the blessed sacrament.

Strolling along the quay past the Welcome Hotel, inhaling deeply the salty air and listening to the sea slapping against the hobbobbing boats moored along the jetty, overwhelming peace reigns in my heart. I then reflect upon what emotions and sentiments Jean Cocteau would have been experiencing as he similarly imbibed the beautiful Mediterranean view.

And then I realize how fortunate I am to be alive and well and have the ability to connect with so many profound beings from the past and present, who teach me how to live in this sacred moment that we call everlasting life.

I lived in this chapel night and day for two years. During five months, I lived in the small Saint Peter nave, fighting with the angel of perspective, rolled up by its vaults, enraptured, embalmed, so to speak, like a pharaoh worried about painting its own sarcophagus, and finally, I became the chapel, and I became a wall … A writer ends up ink and paper, and I became a wall because the stake was that the wall took my place and talked to me. As long as the wall would not talk to me, it was a wall but if it started talking to me, it had me become me. I had changed into a wall, and then, the chapel started to live …

—Jean Cocteau

Photograph: © Éditions du Rocher

Post Notes

- Jean Cocteau’s official website

- Musée Jean Cocteau

- Jean Cocteau, Prince des Poètes

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- Paul Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Saint

- Paula Marvelly: Sacra di San Michele

- Henri Matisse: Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence

- Duncan Grant: Berwick Church

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- Marc Chagall: All Saints’ Tudeley