The art of being on one’s own

“No man should go through life without once experiencing healthy,

even bored solitude in the wilderness,

finding himself depending solely on himself

and thereby learning his true and hidden strength.”

—Jack Kerouac, “Lonesome Traveller”

WHEN I WAS in my teens, I tried reading On The Road, Jack Kerouac’s iconic masterwork. I must admit that I was completely unmoved and dismissed it as a book more suited for restless, adolescent boys wanting to find unattached adventure somewhere over the horizon. As a teenage girl, somewhat predictably, I was more taken with English 19th-century novels and their stories of romantic love and happy ever after.

A vacation in America in my early thirties and a solo road trip from San Francisco to Big Sur in a quest for the meaning of life irrevocably changed all that. Perhaps it was merely a sign of maturity in my literary sensibilities or else it was experiencing first-hand those big red Kerouacian sunsets over the Pacific Ocean, with the warm wind blowing through my hair and a delicious, all-pervading feeling that I was immortal.

Either way, it is with some poignancy that I return once again to his prose in middle age, the same period of his own life when Jack Kerouac (12th March 1922–21st October 1969) passed away, owing to an internal haemorrhage caused by cirrhosis of the liver induced by a lifetime’s alcohol abuse. Given the breadth of his creative output up to this point—novels, short stories, visual art—I feel bereft at the thought of knowing that there were undoubtedly many more incredible things in the offing about which we will sadly never know.

Published in 1960, Lonesome Traveller is a collection of journal entries about Kerouac’s travels through the United States, Mexico, Morocco, the United Kingdom and France. Written in his inimitable “spontaneous prose” style, one particular short story that profoundly impressed me is “Alone on a Mountaintop”, which describes his three-month stay on Desolation Peak, in the North Cascade Mountains of Washington State, as a lone fire lookout:

After all this kind of fanfare, and even more, I came to a point where I needed solitude and just stop the machine of ‘thinking’ and ‘enjoying’ what they call ‘living’, I just wanted to lie in the grass and look at the clouds —

They say, too, in ancient scripture: — ‘Wisdom can only be obtained from the viewpoint of solitude.’

Along with fellow writers Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Herbert Huncke and Lucien Carr, Kerouac is better known as a leading exponent of the Beat Generation, with its rejection of materialism and exploration of spiritual values, as well as experimentation with sex and psychedelic drugs. His “underground” celebrity status did not sit well, however, with Kerouac, who relished the opportunity to head for the hills to find solitude from the “inequalities, frustration and self-inflicted agonies” of the contemporary world.

In an attempt to emulate Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; or, Life in the Woods, by Kerouac’s own admission, he “… was looking forward to an experience men seldom earn in this modern world: complete and comfortable solitude in the wilderness, day and night, sixty-three days and nights to be exact.”

Kerouac would explore his experiences on Desolation Peak in more detail, and somewhat differently, in The Dharma Bums (1958) and Desolation Angels (1965); it is “Alone on a Mountaintop”, however, that distils, rather like a zen koan, his thoughts and perceptions upon being confronted with his naked and vulnerable self.

After traversing a misty lake and a steep, muddy trail for several hours, his muleskinner and mountain guide, Andy, suddenly yells out:

‘There she is!’ and up ahead in the mountaintop gloom I saw a little shadowy peaked shack standing alone on the top of the world and gulped with fear: ‘This is my home all summer? And this is summer?’ The inside of the shack was even more miserable, damp and dirty, leftover groceries and magazines torn to shreds by rats and mice, the floor muddy, the windows impenetrable. — But hardy Old Andy who’d been through this kind of thing all his life got a roaring fire crackling in the potbelly stove and had me lay out a pot of water with almost half a can of coffee in it saying ‘Coffee aint no good ‘less it’s strong!’ and pretty soon the coffee was boiling a nice brown aromatic foam and we got our cups out and drank deep. —

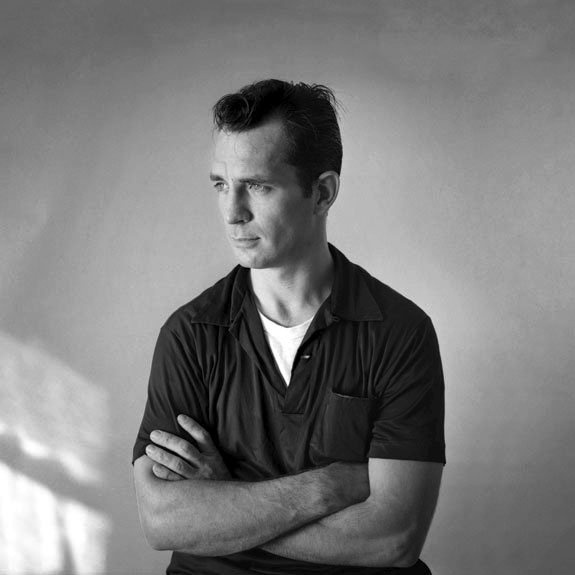

Tom Palumbo, Jack Kerouac.

Image: CC BY-SA 2.0

It doesn’t take Kerouac long to settle into his new mountain abode and develop daily rituals in harmony with his new surroundings:

Most days … it was the routine that occupied me. — Up at seven or so every day, a pot of coffee brought to the boil over a handful of burning twigs, I’d go out into the alpine yard with a cup of coffee hooked in my thumb and leisurely make my wind speed and wind direction and temperature and moisture readings — then, after chopping wood, I’d use the two-way radio and report to the relay station on Sawdough. — At 10 A.M. I usually got hungry for breakfast, and I’d make delicious pancakes, eating them at my little table that was decorated with bouquets of mountain lupine and sprigs of fir. Early in the afternoon was the usual time for my kick of the day, instant chocolate pudding and hot coffee. — Around two or three I’d lie on my back on the meadow side and watch the clouds float by, or pick blueberries and eat them right there. The radio was on loud enough to hear any calls to Desolation. Then at sunset I’d roust up my supper out of cans of yams and Spam and peas, or sometimes just pea soup with corn muffins baked on top of the wood stove in aluminium foil. — Then I’d go out to that precipitous snow slope and shovel two pails of snow for the water tub and gather an armful of fallen firewood from the hillside like the proverbial Old Woman of Japan. —

By this time in his life, Kerouac was deeply passionate about the teachings of the Buddha, having been greatly influenced by Dwight Goddard’s 1932 collection of Classic sutras, A Buddhist Bible, which he stole from a library and continually carried around in his rucksack.

Indeed, prior to his mountain exile, Kerouac had begun an intensive study of the Diamond Sutra or Vajracchedika-prajnaparamita-sutra, a Buddhist text urging devotees to cut through the illusion of the transient world in order to discover the timeless reality beneath.

In a repeating weekly cycle, therefore, Kerouac would devote one day to each of the six paramitas, or perfections, and the seventh day to the concluding passage on samadhi. The Diamond Sutra was his sole reading material on Desolation Peak, by which he hoped to transcend his mind into the emptiness that lies beyond it. Despite the tranquillity of his mountain hermitage and his spiritual practices, life is nevertheless not without its challenges:

In the middle of the night I woke up and suddenly my hair was standing on end — I saw a huge black shadow in my window. — Then I saw that it had a star above it, and realized that this was Mt Hozomeen (8080 feet) looking into my window from miles away near Canada. — I got up from the forlorn bunk with mice scattering underneath and went outside and gasped to see black mountain shapes gianting all around, and not only that but the billowing of the northern lights shifting behind the clouds. — It was a little too much for a city boy — the fear that the Abominable Snowman might be beneath me in the dark sent me back to bed where I buried my head inside my sleeping bag. —

Spectres and shadows abound but the bright light of the following day dispels all illusions:

But in the morning — Sunday, July sixth — I was amazed and overjoyed to see a clear blue sunny sky and down below, like a radiant pure snow sea, the clouds making a marshmallow cover for all the world and all the lake while I abided in warm sunshine among hundreds of miles of snow-white peaks. — I brewed coffee and sang and drank a cup on my drowsy warm doorstep. At noon the clouds vanished and the lake appeared below, beautiful beyond belief, a perfect blue pool twenty-five miles long and more, and the creeks like toy creeks and the timber green and fresh everywhere below and even the joyous little unfolding liquid tracks of vacationists’ fishing boats on the lake and in the lagoons. —

Kerouac’s prose is at its zenith—elegant, pure, impetuous—making it hard to understand how someone who could speak with the tongues of angels would be beset by inner demons and addictions that would ultimately destroy him only a few years later. Then again, it would often seem that those who are blessed with genius must always pay the price:

I just lay on the mountain meadow side in the moonlight, head to grass, and heard the silent recognition of my temporary woes. — Yes, so to try to attain to Nirvana when you’re already there, to attain to the top of a mountain when you’re already there and only have to say — thus, to stay in the Nirvana Bliss, is all I have to do, you have to do, no effort, no path really, no discipline but just to know that all is empty and awake, a Vision and a Movie in God’s Universal Mind (Alaya-Vijnana) and to stay more or less wisely in that. — Because silence itself is the sound of diamonds which cut through anything, the sound of Holy Emptiness, the sound of extinction and bliss, that graveyard silence which is like the slice of an infant’s smile, the sound of eternity, of the blessedness surely to be believed, the sound of nothing-ever-happened-except-God …

And thus Kerouac discovers that being on one’s own is not a prerequisite to discovering peace of mind; rather, the only way out of the desolation of daily life is to turn within, wherever one may be. He then makes a promise to himself: “I decided that when I would go back to the world down there I’d try to keep my mind clear in the midst of murky human ideas smoking like factories on the horizon through which I could walk, forward …”

63 sunsets Kerouac sees revolving on that “perpendicular hill”. September has now descended, like a golden mist, and it is time to leave. Walking down the path leading him back towards civilization, he pauses awhile, taking stock one final time:

As I reached the bend in the trail where the shack would disappear and I would plunge down to the lake to meet the boat that would take me out and home, I turned and blessed Desolation Peak and the little pagoda on top and thanked them for the shelter and the lesson I’d been taught.

Post Notes

- Feature image: Paula Marvelly, Arunachala, India [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

- JackKerouac.com

- The Jack and Stella Kerouac Center for the Public Humanities

- Alexandra David-Néel: My Journey to Lhasa

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Hermann Hesse: The Journey to the East

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- John Adams: The Dharma at Big Sur

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme