IMEALL, Gabriel Rosenstock

The power of the poetic pen

Gabriel Rosenstock is the author/translator of over 150 books, including 13 volumes of poetry and a volume of haiku, mostly in Irish (Gaelic). Prose work includes fiction, essays in The Irish Times, radio plays and travel writing. He has given readings and performances in Europe, US, India, Japan and Australia. He is a member of Aosdána (Irish Academy of Arts & Letters). Broken Angels is the fourth in an ongoing series of ekphrastic tanka books published by Cross-Cultural Communications, New York, and available as a free e-book on the EDOCR platform.

In this week’s guest post for The Culturium, Gabriel discusses the art of transcreating poetry, his Celtic upbringing and how the appreciation of haiku may be a gateway to enlightenment.

You have drowned me.

I am awash in You.

Never again

Will I be a desert

“Spring Showers”

PM: FOR YOU, GABRIEL, what does it mean to be a poet?

Gabriel Rosenstock: As a poet-translator, I take great delight in transcreating poetry from around the world into Irish (using English as a bridge language much of the time) and one such poet, who writes in Malayalam, is K. Satchidanandan. He answers your question beautifully:

My mother taught me to talk to crows and trees; from my pious father I learnt to communicate with gods and spirits. My insane grandmother taught me to create a parallel world to escape the vile ordinariness of the tiresomely humdrum everyday world; the dead taught me to be one with the soil; the wind taught me to move and shake without ever being seen and the rain trained my voice in a thousand modulations. My beautiful village with its poor people too must have hurt me into poetry …

What it means to be a poet is to give oneself, freely, constantly, to the pain and ecstasy which Satchidanandan describes above, to find new ways of giving yourself, spending yourself, creating and recreating yourself, forging words and forms for the formless immensity within and without, a voice with which to sing the sorrows of existence, a song in search of hope, in search of its own beginnings.

To be a poet is to answer that calling in all weathers. The call of the wild. I am a wild man. My mother used to call me (I was hardly nine at the time), “The Wild Man from Borneo”. The poet is one who cannot be tamed, the bear that you cannot chain, the bird that cannot be caged.

There’s a photo of me as a child with some of my siblings and I’m holding a stick, whether I thought it was a crozier or a shillelagh at the time, I don’t know. The image of the Fighting Irish with a shillelagh is a distorted one—before matters degenerated into faction fighting, I believe the shillelagh was a highly sophisticated tool employed in martial arts.

I digress … the tallest boy in the photo was my brother Michael who was only 17 when he drowned in Glendalough. To be a poet, ideally, is to be Everyman.

PM: How does communicating in the Gaelic language, through the broader context of your Celtic inheritance, infuse your work?

Gabriel Rosenstock: Of modern European languages, Irish is the oldest that has a written literature and her myths and legends are pagan, pre-historical, in many ways matching the drama and beauty of the great myths of the ancient world, Greek, Sanskrit, Roman and so on. It is a bottomless treasure pit and if I lived to be a thousand I would not know the half of it.

There are many reasons why its treasures are not widely known. The language almost became extinct. How language loss has damaged the Irish psyche is a tale that is familiar to most postcolonial societies today, though many such societies are in denial of their past. For a shocking analysis of this question, I recommend The Broken Harp by Tomás Mac Síomóin [you will see that I have reviewed it on Amazon].

What can I say about my Celtic inheritance? My mother’s surname was Keane (Ní Chatháin). Her people fled the north of Ireland in the seventeenth century and settled as farmers outside of Athenry, Co. Galway. They entertained the blind, itinerant Gaelic poet Raftery (1779–1835) who sang of their unfailing generosity to him and of his great delight in the company of the lovely Úna Ní Chatháin, a song rarely heard today.

By the time my mother was growing up, Irish was no longer the language of the household so she couldn’t pass it on to us. Nothing but scraps. She went nursing to Jersey and the next thing you know, the Channel Islands were invaded by the Germans; in the ranks of the Wehrmacht was her future husband, my father, a medical student and litterateur. She was a very gifted storyteller and wrote a memoir of her war years, Hello, Is it All Over?

How is it that I embraced a language, which neither my mother nor my father spoke? The Irish language was the Other; it was the Outsider; it was the Leper; the Jew; the Witch; the Devil; the Ghost; the Zombie; the Crow; the Banshee; the Wind; the Lake; the River; the Mountain; the Sea; the Shadow, the Murmur; the Old Woman of the Roads; it was everything, all around us but Silent, Incomprehensible, Dying, Alone. An Enigma. (Not of course to the native speakers for whom it was their daily language; not some lost artefact awaiting a Dr Indiana Jones.)

I rushed to her, to embrace her, be embraced by her, to be the Wind, to be the River, the Dolmen, to be the Nameless One, to lose myself in her, or find myself—to see that Old Hag turning into a radiant young queen through the mantric power of a new generation of poets whose mission on earth was but to adore her.

The Revival was also a mystic, alchemic quest in itself—and we would be transformed by it, much as the Pastor in New Finnish Grammar, Diego Marani’s novel, who experiences language in an almost psychedelic way. Meanwhile, the official language revival movement kept well away from such goings on (which were internal and invisible anyway). When you give yourself and of yourself passionately, totally, to anything or anybody, it is never in vain.

I’m so happy that my wife, Eithne, and I managed to rear our four children as native Irish speakers in Dublin, the heart of the English Pale. Anything is possible! It means they can listen to a song in Irish and understand it, feel it—something which hundreds of thousands of their fellow-citizens are unable or unwilling to do. When I heard the song “Pé’n Éirinn Í” as a young blade, somehow I knew my life would have been incomplete—perhaps even wretched—had I never heard it. I found a beautiful rendering of it on YouTube.

PM: Turning now specifically to spirituality, you have spoken of your dissatisfaction with the artistic iconography of the Christian faith, i.e. the suffering, bloodied image of Christ on the Cross, and how you were drawn to the more joyous and beautiful symbolism of the East, for example the smiling Buddha and the radiant Krishna. At a deeper level, in which way did Eastern spirituality inspire you in a way that Christianity, or any other Western religion, couldn’t?

Gabriel Rosenstock: Krishna consciousness, Christ consciousness, ultimately they are the same. The differences are cultural and historical, that is all; concentrating on accidental differences is a form of sectarian bigotry. Why I am attracted more to Krishna than to Christ is purely a matter of vasanas; there are no rational explanations for such vasanas or proclivities and I doubt if psychology can fully explain them. Vasanas remain a mystery and yet explain a lot.

As a child I would close my eyes tightly before going to sleep and instead of seeing a black, blank screen I saw what appeared to be the tiniest of stars—mere pinpoints, numberless—and gazing on these every night was my own form of meditation, so much so that when I first read The Merchant of Venice I thought the following lines were Jessica’s initiation into the mysteries of meditation:

Sit, Jessica. Look how the floor of heaven

Is thick inlaid with patens of bright gold.

There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still choiring to the young-eyed cherubins.

Such harmony is in immortal souls,

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.

—William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice (5.1.56–63)

Those early meditations were buried but not quite forgotten and when I learned TM it all came back to me in a flash. Am I more of a Hindu now than a Christian? Catholicism is my cultural background and there’s no reason to shake it off entirely. I have written positively about such priests as Fr Anthony de Mello, Fr Henri la Saux, Fr John Main, Fr Thomas Merton and so on; I can sense that their experience of meditation was totally genuine.

Fr Teilhard de Chardin (most of these guys don’t come with official Church approval, of course) says that we are spiritual beings having a human experience not the other way around. Fine. But would de Chardin approve of Archbishop Romero, for instance? Maybe Quakers and Kimbanguists might escape the scrutiny of a forensic accountant but most Christian churches—Catholic, Protestant, Mormon, etc.—are complicit in financial corruption and fraud and never tire of giving their blessings to “the war effort” and so on.

The Christ who upset the tables of the money lenders in the temple is the Christ needed today in the light of the scandals surrounding banks and offshore accounts. The symbol that was held aloft was the Cross, not OM, when indigenous cultures and languages were being wiped out all over the planet. My friend, the late Francisco X. Alarcón, has a powerful prayer, which I blogged recently in Spanish, English, Irish and Scots.

Along the same political lines, here’s a haiku I wrote in response to Alfredo Rostgaard’s striking image of Christ:

féachann sé isteach

i gcroí gach caipitlí –

Críost treallchogaíhe sees into the heart

of every capitalist –

guerrilla Christ

—Gabriel Rosenstock

Alarcón had an instinctual feeling for the sacredness of the poetic word. I invited him to Ireland for the launch of a book of his that I had translated into Irish, Cuerpo en llamas. Each reading started with burning sage in a seashell and as the aroma filled the air, he would chant an invocation in Nahuatl.

One of his last publications was a volume called Poetry of Resistance, which he co-edited. My spiritual path has led me to anarchism, to resistance. Vinoba says all revolutions have a spiritual origin and Frantz Fanon says that ultimately it is the possibility of love that fired such seminal works of his as The Wretched of the Earth; love, yes, not blind enmity.

PM: Are there any Oriental poets with whom you feel a particular resonance?

Gabriel Rosenstock: Two of my favourite living poets are Ko Un (Korea) and Cathal Ó Searcaigh (Ireland). But you said Oriental, yes? Yes! Yeats says that before the Battle of the Boyne, Ireland belonged to Asia. In many respects, Ó Searcaigh is more Eastern than Western.

Here’s a poem of his, Kathmandu and her affairs, in my translation of the original Irish. A language that can produce such poetry is, hopefully, far from the throes of death, though some believe it may well be among the three thousand languages doomed to bite the dust before the end of our century.

Day breaks out and she wakes me up suddenly

With a cock-crow kiss!

Looking out from the top window

I spy her in the streets, parading her morning saffron sari.

Her breath in traffic flow, pure draught of heat.She’s on her feet now, no time to rest,

Her clutch about her;

She rouses them with a noisy jackdaw voice, puts the skids under them,

Humouring them so that they might face this day breezily –

A day rising out from the yellowing globe of her eye.Lunch hour, from the hotel balcony, I see her

Stretched in slumber,

Her urban contours lying awkwardly, dog tired,

Her bazaar bosom heaving, exhausted,

The dangerous laneways of her combed tresses.Today the poor are huddled

In the backstreets of her cloak, fretful,

Their wants, their needs pierce her

And how she sighs over and over again when the strong

Walk all over the weak – kid goat teaching its mother to bleat.Tutelary spirit of street shrines, wonder-woman of broken palaces,

Wise one of crumbling courtyards.

A while ago her sky-eyes darkened and she wept with consternation

Seeing her family rising up in rebellion

Against all oppressors.The softness of prayer in her wild words

As her body supports scaffolding –

Stink of pus in her bones –

In spite of this she sings a song of hope

In the cries of protesters, blossoming tongue of youth.Evening. Pagoda-shaped she is,

Bright gems glisten in her ears;

She walks a stately walk among her own, blesses them

With incense chatter: hear the little peals of laughter

As she banters with market ladies, fiery eyed.Night. She spreads the bright

Head-dress of darkness

Over all, her satin cloak

Encrusted with silver brooches, an amber moon

Her torch, traffic horns her hum.To her I will lift my eyes, my soul’s nurse,

When midnight rings

And I stretch my limbs; she comes to me with a sleeping-draught

Full of giddy sparks from the sky. As she departs

She leaves a star in the window, sweet and soft as her kiss.

—Cathal Ó Searcaigh, Kathmandu and her affairs, trans. Gabriel Rosenstock

Returning to your question! I was a very young man when I picked up Speaking of Shiva, a Penguin Classics volume, edited by A. K. Ramanujan (1929–1993). It toppled my worldview. Forty years would go by before I would be able to attempt to write poetry with a bhakti flavour. Bhakti, an outpouring of divine love; the heart melts and love flows in a torrent of song and poetry. The heart catches fire and syllables come together to form tongues of living flame.

I was in Germany, at a festival of profane poetry (!), which turned into a festival of sacred poetry for me. I met someone at the festival who was on her way to have the darshan of Mother Meera and though exchanging no more than a few words with her, this person, miraculously, became a muse-goddess for me.

Two hundred poems ensued, starting in August 2000, poems of ecstasy which could never have been written, I imagine, had not a seed been planted by the Ramanujan volume, a seed watered by subsequent meditations on the bhakti and Advaita traditions of India—and all this eventually flowered in the realization that a hymn to the divine is a recognition of the divine in oneself: so, the other is none other than the Self.

Years would go by before I whittled the poems down and the book was eventually published as Uttering Her Name (Salmon Poetry, 2009). It coincided with my learning how to use email so the poems were sent to the muse-goddess in question in English as this was the only common language between us.

I had rejected English as a medium of poetry up until then. I subsequently wrote a bilingual volume in Irish and English called Bliain an Bhandé, Year of the Goddess, which has some experimental use of typography to express so-called higher states of consciousness. [Contact The Culturium if you would like to receive a free, later edition.]

This time round, the muse-goddess was none other than Ireland herself. You see, many poets writing in Irish have no allegiance whatsoever to Ireland. The entity that interests them is the much older one, Éire (or Ériu), who together with her sisters Banba and Fódla, is the tripartite goddess beloved of poets throughout the ages. So, that was my fling with bhakti.

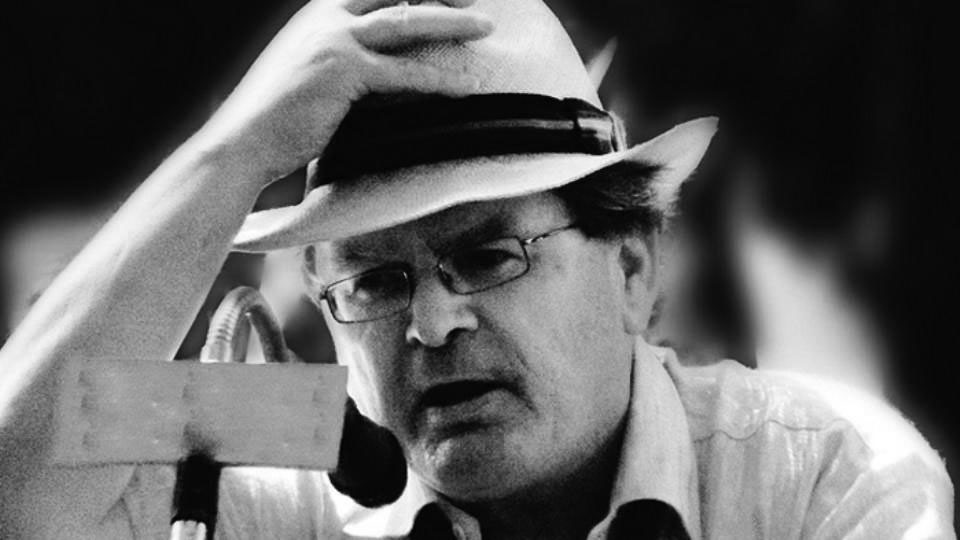

Photograph: © The Irish Times

PM: You are predominantly known as a composer of haiku and have explained how the 17-syllable verse formation is very distinct from a poem. You have also said that a haiku is an expression of the nature of silence. Could you expand on that?

Gabriel Rosenstock: I am not a “composer” of haiku in a sense of deliberately crafting and shaping a work of art we call haiku. Haiku “happen” through me without conscious effort; the spontaneity associated with bhakti utterances, alluded to above, is also central to haiku. The 17-syllable rule has outgrown its usefulness in the West but one should not go beyond 17 syllables or the compression that gives it its energy is gone.

The frivolousness associated with Japanese haiku in Bashō’s time ended when he wrote the following haiku, a haiku surrounded by a great silence:

on a bare branch

a crow alights

autumn evening

—Bashō

I can hear a radiating silence all around this haiku. Can you? It helps that haiku have no title, no full stop at the end: we have entered the haiku, in media res, and it continues without us, into infinity. Where did it come from?

Daisetz Suzuki says that there is a great Beyond in the lonely crow “perching on the dead branch of a tree. All things come out of an unknown abyss of mystery and through every one of them we can have a peep into the abyss …”

I approach haiku with a reverence, even in my irreverent haiku. I have over a dozen unpublished collections of ekphrastic haiku, haiku in response to works of art or photography. If you look at the haiku blogged in response to the work of American master photographer, Ron Rosenstock (no relation), I think you will agree that both the haiku and the landscapes are permeated and perfumed by silence.

Spontaneous haiku are acts of meditation and meditation leads us to Silence and the Self; in other words we can never get in touch with Reality, with Truth, without entering Silence.

PM: In an interview with the online radio show, Poetic Synergy, you said, “If you come to a complete understanding of the nature of the Self, then the desire to express oneself will wane. [But] you must also pay respect to your own nature as a poet.”

Without sounding disrespectful to your work, there is a story to which I would like to refer in Arthur Osbourne’s The Mind of Ramana Maharshi. When asked by a visiting poet to the Ramanasramam for permission to write poems in praise of the great Indian master, Sri Ramana remarked, “All this is only activity of the mind. The more you exercise the mind and the more success you have in composing verses, the less peace you have.”

I am keen to understand if creativity can ever be devoid of ego or mental activity, and if so, whence does it come and what specific purpose does it serve?

Gabriel Rosenstock: Let’s not forget that Sri Ramana composed poetry himself, such as The Marital Garland of Letters. We know that tears came to his eyes when works by Tamil poet-saints were read aloud to him.

Sri Ramana gave the best advice I have ever heard on the question of Self-Realization. He insisted there are only four paths available: firstly, Self-inquiry; secondly, bhakti; thirdly, selfless service to mankind; fourthly, the pursuit of beauty. It is perfectly clear, at least to me, that a poet can be on one or more of these paths but she or he must know of the need for constant awareness.

Self-deception is a hair’s breadth away (or a hare’s breath, as a child might hear that expression and as the child in me hears such things all the time!). Perhaps what Sri Ramana had in mind is egoic poetry. This gives none of us any peace, least of all the poet! The greatest works of creativity are devoid of ego: the sheer power of beauty in a great work of art shatters the ego and pure Spirit arises, radiant, eternal.

I believe haiku, when properly used, can be the ego-shatterer par excellence. Here is the great Afro-American haiku master, Richard Wright:

I am nobody:

a red sinking autumn sun

has taken my name away

Seisensui Ogawa, who broke with haiku convention, was the haiku teacher of two extraordinary geniuses, Santōka Taneda and Hōsai Ozaki. He said of the latter:

To cast away everything and feel like the big sky of blueness itself was his ideal; in the big sky there is nothing; there may be clouds, but they will eventually disappear.

How to divest oneself of the ego? Dogen (1200–1253) tells us to shuffle off body and mind—shinjin datsuraku. This is what Santōka succeeded in doing—not every minute of every day but those clouds will yield eventually to the broad expanse of sky. And it need not be an arduous task, though for Santōka and Ozaki it was far from easy. But it can even be pleasurable, believe it or not.

I have written two books about haiku as a way of life, Haiku Enlightenment and Haiku: The Gentle Art of Disappearing. In a word, the art of haiku is that of interpenetration. “Go to the pine,” says Bashō, and we may add, “Leave your ego behind you!” Do that every day, day in day out, and eventually the ego gets tired coming back all the time and stays away, for a while. To get a second wind.

The ego is devilishly clever. You think you’ve clobbered it with your shillelagh but it’s not even stunned; it has split into several sub-entities that can reveal themselves in dreams, desires and the plethora of demons that populate all our myths and legends. Pure haiku can cut through them again and again and we can momentarily dwell in the unclouded Self.

I hear an objection: how can Rosenstock talk of egolessness while at the same time promoting his books as he does above—and shamelessly at that!? The answer is with a question: how do you know if I am interested or disinterested in promoting those book titles, if promotion it be? Ego can be used to undermine ego. Fight fire with fire.

We have an expression in Irish, ding de féin a scoilteann an leamhán—with a wedge of its own timber is the elm split! The mind can be used to understand how fickle the mind is—this is enlightenment as taught by Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj, is it not?

The Anglo-Irish Daoist philosopher, Wei Wu Wei, explains the difference between a saint and a sage. The saint is one who disciplines the ego; the sage is One who drops it. That’s all that’s needed. One is not required to wear a hair shirt and lock oneself away in a cave.

PM: As you have alluded to above, it is said that the path to enlightenment, according to the teachings of Advaita Vedanta, is principally either through knowledge (jnana) or surrender (bhakti). You have said that the composing and appreciation of poetry can also lead to enlightenment, similar to Sri Ramana’s evocation of the pursuit of beauty, so how does poetry encompass the way of the head and/or the way of the heart?

Gabriel Rosenstock: It is neither the way of the head, fully, nor the way of the heart, fully, since poetry opens up a living channel between both. Each is capable of informing the other.

Poetry today has imprisoned itself in academia, however, and the balance between heart and head has been disrupted. The heart must come to the rescue. Since earliest times, there have always been poets for whom language is alive—as a living deity may be said to be alive in the heart of the devotee.

Some languages—and Irish is one of them—demand great love and undying devotion from their acolytes, their poets. My poetic ritual is a surrender to the living mystery of language itself, as a feminine deity in her own right.

Thus, my belief is that language is essentially sacred, alive, growing, a source of grace, wisdom and beauty in our lives. Our engagement with language can be sacramental, holy. One can feel it in Whitman but most of what is written in English today is spiritually barren and its lack of cadence and euphony bears witness to this sorry wasteland.

PM: Are there any other Western poets other than Walt Whitman in your opinion who have the same mystical insight as those of the East?

Gabriel Rosenstock: Shakespeare is the supreme poetic dramatist, gifted with cosmic consciousness. I’d rather not make a list. People should have a look at the website Poetry Chaikhana, Sacred Poetry from around the World and make up their own minds. What may not speak to you now may speak to you at another time. It’s a question of readiness—and vasanas of course.

PM: Wassily Kandinsky said, “A painter, who finds no satisfaction in mere representation, however artistic, in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art.” Would you say this also applies to the poet?

Gabriel Rosenstock: Yes. Nirmal Kumar says, “Art is essentially the product of inner music.” (The Stream of Indian Culture.) This applies to poetry as well, poetry that is connected to that most beautiful musical instrument, the voice. I cannot read poetry that has lost its voice.

PM: You also write poetry for children. Given the subtle and often complex nature of verse, what is the value of writing and learning poetry at an early age?

Gabriel Rosenstock: The more poems and songs we learn the better, especially folksongs that have stood the test of time. Carving up poems for their meaning and giving children prose versions as an explanation is as barbaric as vivisection. As we grow older, it is good to listen to chant as well. I listen to sacred chant almost every day. The Mahamrityunjaya Mantra sung by Hein Braat is a favourite.

I’m sure that poetry had its origins in chant. Whitman was influenced by chant. Communal chanting can be used for political and religious purposes and is related to the rhymes and games that children played before, in our wisdom, we glued them all to gadgets. Communal chant subverts the ego. Anything that subverts the ego is to be welcome.

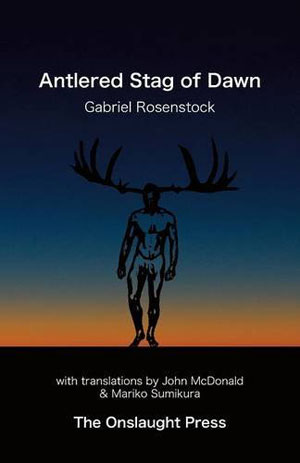

Gabriel’s latest title, inspired by gazing on a photograph of the Very Reverend Chögyam Trungpa in Highland regalia is Antlered Stag of Dawn, haiku in Irish, English, Scots and Japanese, published by The Onslaught Press, Oxford.

Post Notes

- Gabriel Rosenstock’s Amazon page

- Gabriel Rosenstock’s blog

- The Haiku Foundation Digital Library

- Jason Symes & Gabriel Rosenstock, Rare Times

- Masood Hussain & Gabriel Rosenstock: Love Letter to Kashmir

- Kon Markogiannis, Gabriel Rosenstock & Sarah Thilykou: Angelic Flights

- Debiprasad Mukherjee & Gabriel Rosenstock: Last Stop Before Salvation

- Peter Donnelly: The Harvest Bow, Seamus Heaney

- Alicia Torres: Darshan

- Matsuo Bashō: Deep Silence

- Dennis Gallagher: The Power of the Pen

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Debiprasad Mukherjee: Mural World

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Illumination