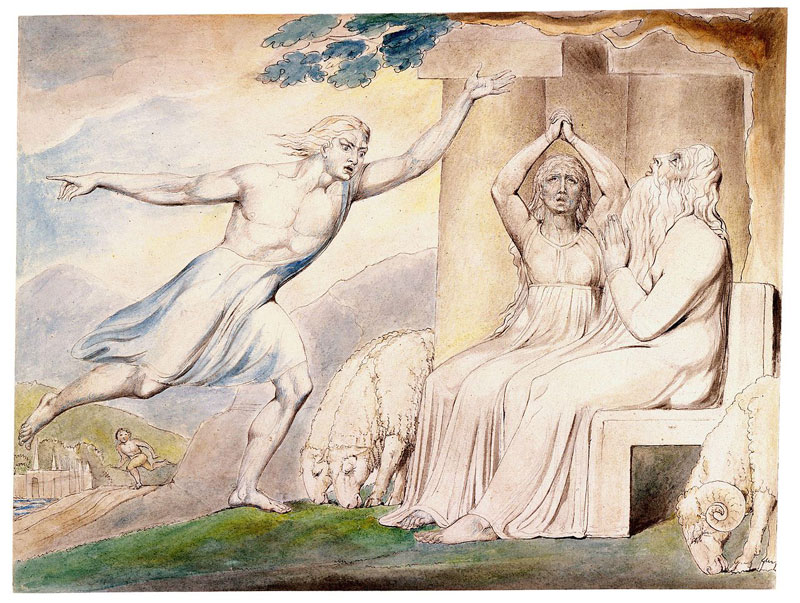

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

The marriage of heaven and hell

Eric Nicholson is a retired art teacher living in the north-east of England. He is a member of Newcastle’s Literary & Philosophical Society and enjoys countryside conservation, writing, singing in a choir and fell-walking. In this week’s guest post for The Culturium, Eric reflects upon the way in which William Blake’s illustrations of the Book of Job are a beautiful visual depiction of the individual’s inner passage from turmoil and hopelessness to freedom and release.

“I am presently writing a book about Blake’s Job engravings and exploring how his visual narrative relates to our own spiritual journeys. As a Soto Zen Buddhist, I am particularly intrigued with Blake’s system of regeneration; how to, in his well known words, ‘cleanse the doors of perception’, and even, how to overcome the extreme human experience of despair. My first attempt at a full-length book was one about Renaissance Art and Self-Enquiry. For the last year, I have been looking at Blake’s Job engravings and paintings and quickly realized that Blake’s re-interpretation of the Job narrative had parallels with the Buddhist idea of dukkha or suffering and how best to deal with it. The following is an extract from the Introduction to my second book.”

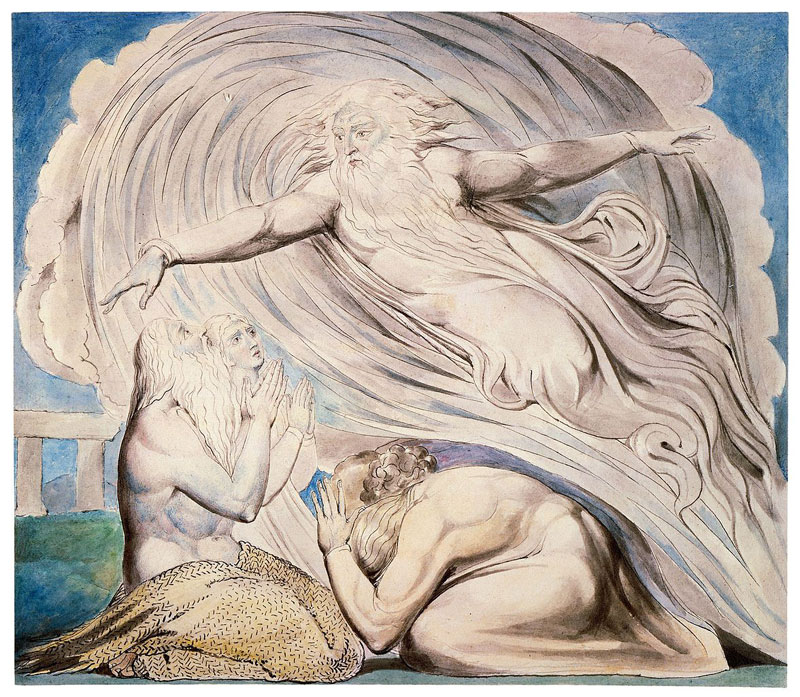

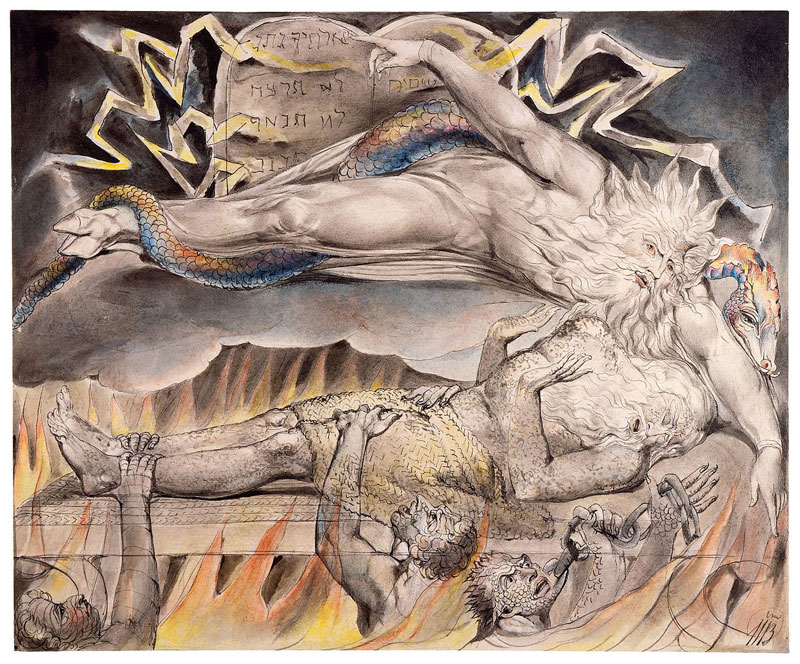

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

“All the while my breath is in me, and the spirit of God is in my nostrils;

My lips shall not speak wickedness, nor my tongue utter deceit.”

—The Book of Job, 27:3

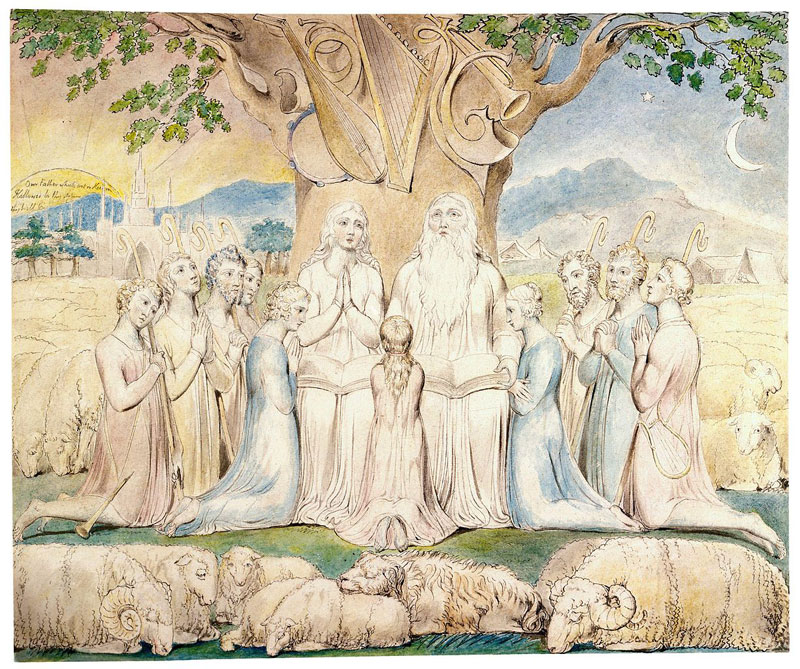

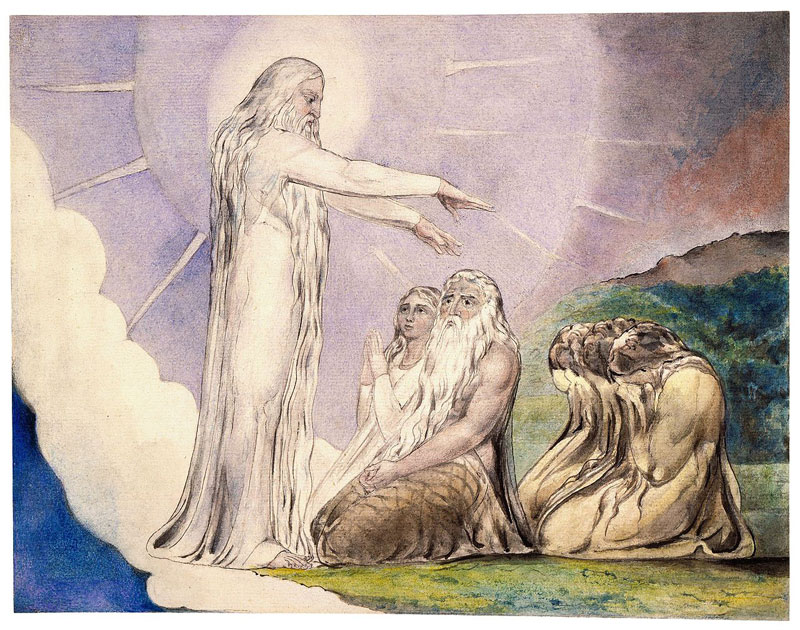

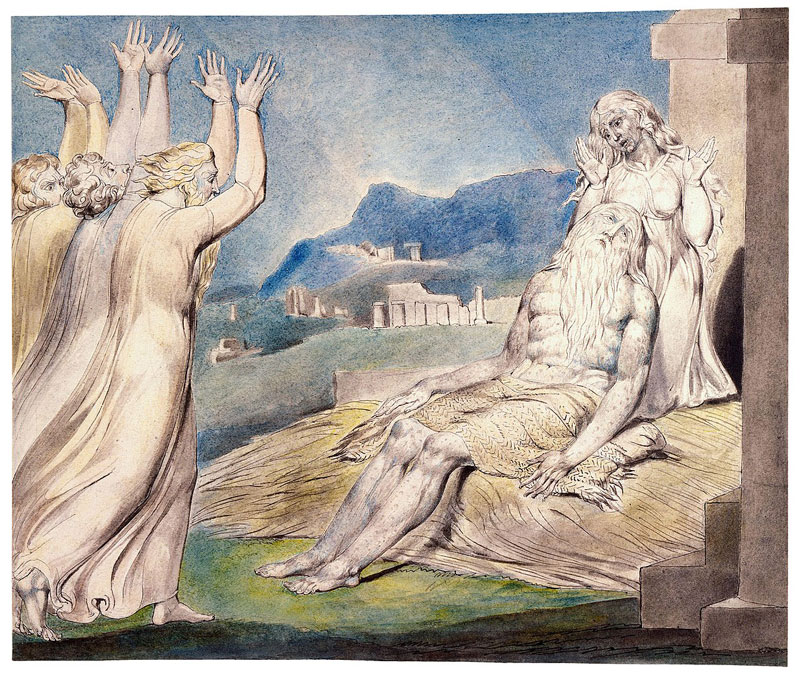

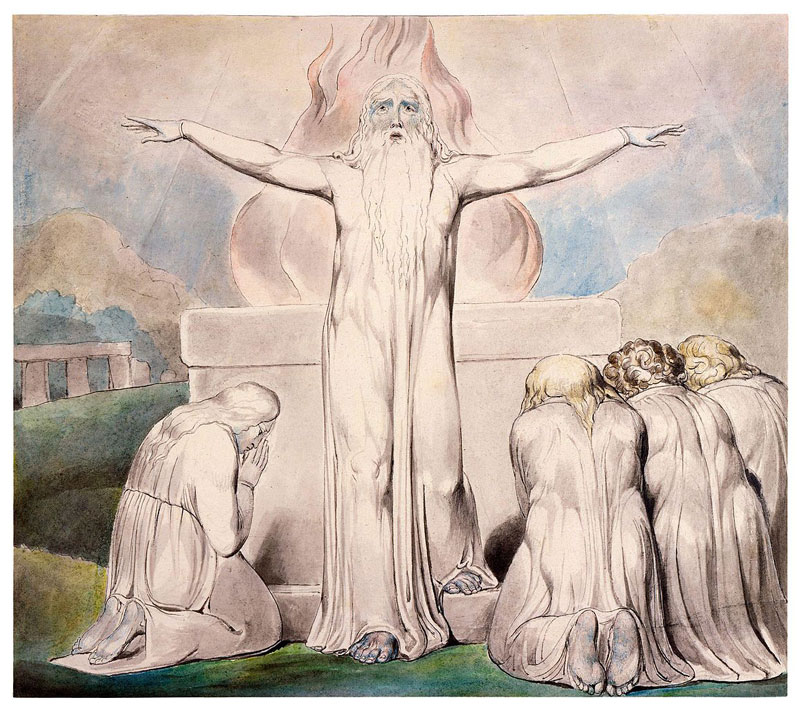

WILLIAM BLAKE’S TWENTY-TWO engravings about the biblical Book of Job are the culmination of a forty-year preoccupation with the subject. In the mid 1780s, he completed a drawing showing Job’s wife and his friends. This was followed by nineteen stunning watercolours illustrating the whole narrative of Job but filtered through Blake’s unique vision. In 1821, John Linnell borrowed the watercolours and traced the series, which Blake then coloured. Two years later, Linnell commissioned the engravings that Blake made on copperplates using a “relief line” technique. Considering the small size of the black and white prints (8.4 x 6.5 inch), the richness of both the pictorial elements and the intellectual content is astonishing. It is no wonder that these final Job engravings, made near the end of Blake’s life, are so deeply felt and masterful in technique. Nietzsche said something about if you stare long enough at the abyss, the abyss will stare back. This seems to be what Blake did; in any case his positive vision has been created in the crucible of his own suffering.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

I give you the end of a golden string,

Only wind it into a ball,

It will lead you in at Heaven’s gate

Built in Jerusalem’s wall.

—William Blake, “And did those feet in ancient time” (aka “Jerusalem”),

Milton: A Poem in Two Books

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

[Eric Nicholson’s commentary on William Blake’s illustrations of the Book of Job, complete with twenty-two engravings, will be published in 2018.]

Post Notes

- Eric Nicholson’s blog

- The William Blake Archive

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art