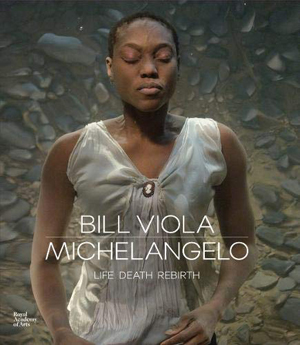

Bill Viola, Fire Woman, 2005

The intimacy between spirituality and art

Sol pur col foco il fabbro il ferro stende

al concetto suo caro e bel lavoro,

né senza foco alcuno artista l’oro

al sommo grado suo raffina e rende;

né l’unica fenice sé riprende

se non prim’arsa; ond’io, s’ardendo moro,

spero più chiar resurger tra coloro

che morte accresce e ’l tempo non offende.

Del foco, di ch’i’ parlo, ho gran ventura

c’ancor per rinnovarmi abbi in me loco,10

sendo già quasi nel numer de’ morti.

O ver, s’al cielo ascende per natura,

al suo elemento, e ch’io converso in foco

sie, come fie che seco non mi porti?

It is only with fire that a smith can shape iron into

a beautiful and cherished work in accordance

with his concept, and without fire no craftsman

can refine his gold and bring it to the highest

quality;

nor can the unique phoenix recover life

unless it first be burned; likewise, if I die by

burning, I hope to rise again to a purer life among

those whom death enriches and time no longer

harms.

It is my good fortune that the fire of which I

speak has even now taken hold in me to renew

me, when I am already almost numbered among

the dead.

How can it be, then, if fire by nature ascends

to the heavens, to its proper sphere, and I am

turned to that fire, that it does not carry me upwards

along with it?

—Michelangelo, ‘Sonnet 62’

LIKE THE REST of the world, I watched aghast as images of the recent fire at the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris were broadcast across international media and witnessed not only the partial collapse of an outstanding architectural monument but also the chambers of my innermost heart. And yet in the aftermath of such a devastating tragedy, which has shown unprecedented public support and solidarity in a pledge to restore the church to its former glory, we are once again given testament to the intimate connection between art and spirituality and the way in which they are intrinsically seared into the human soul.

Furthermore, Greek thinker, Empedocles, who was the first to propose the universal constituents of matter, which he called the four “roots” —earth, air, fire, water—and which Plato later referred to as “elements”, it is clear for all to see how these alchemical components ignite a deep and intuitive connection between phenomena and consciousness, made all the more potent when glorified, wittingly or even unwittingly, through the archetypal power of transcendental art.

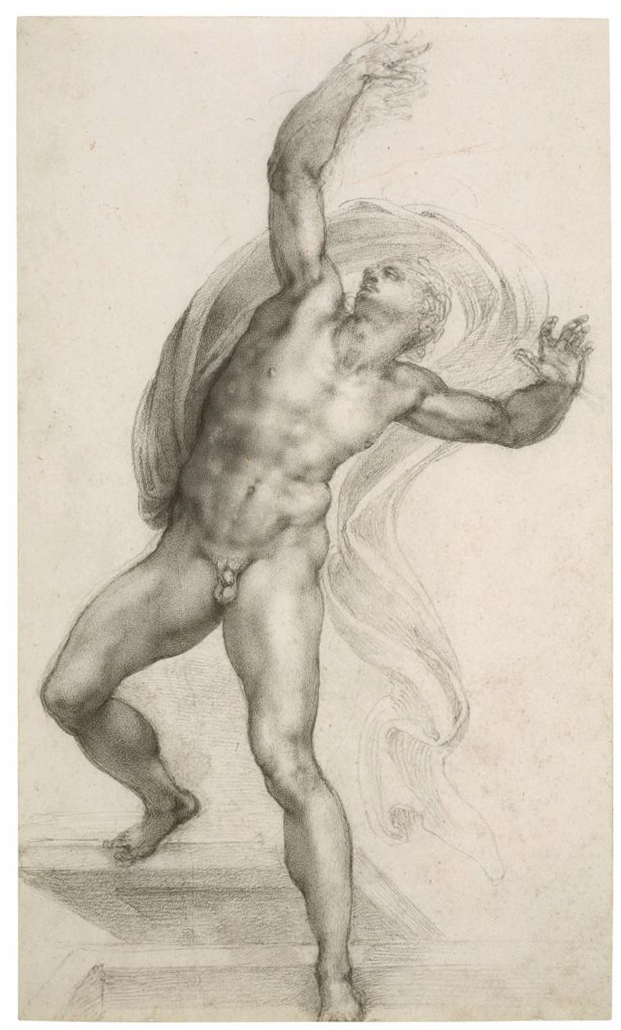

Black chalk on paper, 37.2 x 22.1 cm

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

My interest in the various systems of the cultures of the world involves a search for the image that is not an image. This is why I am not interested in ‘realistic’ rendering. Sacred art seems very close because of its symbolic nature. Its intrinsic interwoven meaning on other planes makes it more ‘conceptual’. I am interested not so much in the image whose source lies in the phenomenal world but rather the image as artefact or result or imprint or even wholly determined by some inner realization. It is the image of that inner state and as such must be considered completely accurate and realistic. This is an approach to images from an entirely opposite direction—from within rather than without … Perhaps one of the most difficult tasks of the contemporary artist is not to become swamped by the number of techno-tools capable of precision rendering of the visible world (photo, film, video) and to create with these systems the ‘pure’ images of the symbolic …

I have learnt so much from my work with video and sound, and it goes far beyond simply what I need to apply within my profession. The real investigation is that of life and of being itself; the medium is just a tool in this investigation. I am disturbed by the overemphasis on technology, particularly in America—the infatuation with high-tech gadgets. This is also why I don’t like the label ‘video artist’. I consider myself to be an artist. I happen to use video because I live in the last part of the twentieth century and the medium of video (or television) is clearly the most relevant visual art form in contemporary life. The thread running through all art has always been the same.

—Bill Viola

In an intriguing juxtaposition of creative expression, the Royal Academy of Arts in London recently showcased the work of artist, Bill Viola (born 1951), and the drawings of Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6th March 1475–18th February 1564). To the casual eye, it was a perplexing pairing and yet having witnessed the exhibition firsthand, I was overawed by the way in which two seminal artists were brought together, unified in their abiding preoccupation with love, life, death and the passing of time, despite working in radically different media half a millennia apart.

Indeed, walking through the cavernous rooms of the RA, naked bodies rising and falling and rising and falling and rising again all about me, I felt as if my struggles as a human being trying to make sense of a chaotic universe were not only shared by my visual counterparts but that they gave my plight grace, nobility and meaning through their simple acts of living and dying and being reborn.

Video/sound installation

Performer: Robin Bonaccorsi

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Personally, it was most important for me being there [in Florence] to feel art history come alive off the pages of books, to soak into my skin. I probably had my first unconscious experiences then of art as related to the body, for many of the works of the period, from large public sculpture to the architecturally integrated painting in the churches, are a form of installation—a physical, spatial, totally consuming experience … I spent most of my time in pre-Renaissance spaces—the great cathedrals and churches. At the time I was very involved with sound and acoustics and this remains an important basis of my work. Places like the Duomo were revelations for me. I spent many long hours staying there inside, not with a sketchbook but an audio tape recorder. I eventually made a series of acoustic records of much of the religious architecture of the city. It impressed me that regardless of one’s religious beliefs, the enormous resonant stone halls of the mediaeval cathedrals have an undeniable effect on the inner state of the viewer …

What happened over the years is that through my travels and experiences in other cultures, first in Florence and then primarily in non-Western cultures in the Pacific, Southeast Asia, and especially Japan, and in combination with my readings in ancient philosophy and religion, I began to be aware of a deeper tradition, an undercurrent stretching across history and cultures … the ancient spiritual tradition that’s concerned with self-knowledge, that we can see in ancient Greece and all the great religions, in Early Christianity as well as Siberian shamanism, what Aldous Huxley called the ‘perennial philosophy’, the link between East and West.

—Bill Viola

Over a four-decades’ career working as a pioneer in video media, Bill Viola’s art has explored the fundamental themes of mankind’s existence—the tumult of daily living; the search for solace and transcendence; the passing of the physical body and the possibility of rebirth. Half a century ago, Michelangelo was similarly investigating motifs related to intimacy, mortality, resurrection and the pathos of the human condition through his paintings, poetry and sculpture.

Despite the essence of their work expressing profoundly spiritual compositions, neither artist is tethered to a religious orthodoxy or philosophical belief; rather, both draw upon and integrate diverse elements from many creeds and cultures. Michelangelo investigated Christian concepts infused with Neoplatonic philosophy, which emphasized the immortality of the soul; Bill Viola explores the mystical teachings of all the great wisdom traditions, with prominence given to the concept of self-awareness, the knower-known duality and the nature of mind.

Video/sound installation

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Pneuma is an ancient Greek word that has no equivalent in contemporary terms. Commonly translated as soul or spirit, it refers as well to breath and was conceived as an underlying essence or life force, which runs through all things of nature, animating or illuminating them with Mind … Indistinct, shifting and shadowy, the projections become more like memories or internal sensations rather than recorded images of actual places and events, surrounding and submerging the viewer in their essence …

When a life ends, when someone exhales their last breath, they literally, physically, become stillness—they become eternity itself. The shock of witnessing the end of a life is that you’re seeing the end of time … the cessation of all movement. You’re looking at the end of any possibility for change. When my mother took her last breath, the finality was deafening. I will never forget this moment.

—Bill Viola

The Royal Academy exhibition comprises 15 works by Michelangelo, 12 of which are loaned by Her Majesty the Queen from the Royal Collection, including the exquisitely executed, The Risen Christ, as well as 12 major video installations by Bill Viola, incorporating The Reflecting Pool (1977–79), The Sleep of Reason (1988), The Messenger (1996), Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity (2013), The Dreamers (2013), and Five Angels for the Millennium (2001). One particularly moving work, which is quite literally a meditation on life and death, is Nantes Triptych (1992); a central video panel of a clothed man floating in water, bardo-esque, is flanked either side by a woman in the process of giving birth and an old woman in the process of dying and who is also, in fact, Bill Viola’s mother.

Writing in a journal at Chicago O’Hare airport in transit between LAX and Lyon some time later, as he watches the other passengers, Bill Viola’s thoughts are filled with reflections on the nature of existence: “My heart is pulled down, along with them, to the space below, beneath their feet, under the legs of these tables, below the speckled terrazzo floor—the root source that props them up as I write, always, that gives them speech and longings and memories and breath. Belief is all there is—the solid form that holds all this up, the casing, the shell from the casting of the mould of many forms. Tears are the purest expression and the only possible reaction to the depth and true import of all this.”

Video/sound installation

Performer: John Hay

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Know the world is a mirror from head to foot,

In every atom are a hundred blazing suns.

If you cleave the heart of one drop of water,

A hundred pure oceans emerge from it.

If you examine closely each grain of sand,

A thousand atoms may be see in it.

In its members a gnat is like an elephant.

In its qualities a drop of rain is like the Nile.

The heart of a barley-corn equals a hundred harvests,

A world dwells in the heart of a millet seed.

In the wing of a gnat is the ocean of life.

In the pupil of the eye a heaven:

What though the grain of the heart be small

It is a station of the Lord of both worlds to dwell therein.

—Bill Viola

For me, by far and away the sublimest installations were to be found in the final room of the exhibition, which ran on a continuous loop, each high-definition video projection displayed alternately on a single screen. Both works are part of a four-hour video created for Peter Sellar’s production of Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde at the Paris Opéra in 2005 and which address the sacramental nature of fire and water.

Fire Woman (2005) is an image seen in the mind’s eye of a dying man. The darkened silhouette of a woman stands before a wall of flame; after several minutes, she moves forward, opens her arms and falls into her own reflection. When the flames of passion finally engulf the inner eye and blind the seer, the reflecting surface collapses into its essential form—undulating wave patterns of pure light. Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall) (2005) describes the ascent of the soul in the space after death as it is awakened and drawn up in a backwards-flowing waterfall; small drips morph into light rain and then a roaring deluge, the cascading water drawing the soul ever upwards, disappearing above.

Black chalk, 28.1 x 26.8 cm

The British Museum, London. Exchanged with Colnaghi, 1896, 1896,0710.1

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Representing artistically the permanence of the soul in relation to the insubstantiality of the body is a theme that has challenged creatives from time immemorial and is often best apprehended when the material realm is resolved into Plato’s four classical elements, of which fire and water are employed explicitly and extensively throughout both artists’ work. Indeed, water is Bill Viola’s most recurring motif, one which he attributes to his near-drowning experience while on holiday as a young child: “I had no fear. I was witnessing this extraordinarily beautiful world with light filtering down … it was like paradise. I didn’t know that I was drowning … For a moment there was absolute bliss.”

Coupled with fire, Bill Viola is further able to capture the dualistic essence of the human condition, as do both Michelangelo and indeed the RA exhibition overall, bringing together a perfect synthesis of opposites, a syzygy of the ineffable with the transitory, a simultaneous fusion of being and non-being, obliterated in the immanent component of life itself: “The two traditional elements of fire and water appear … not only in destructive aspects but manifest their cathartic, purifying, transformative and regenerative capacities as well. In this way, self-annihilation becomes a necessary means to transcendence and liberation.”

Giunto è già ’l corso della vita mia,

con tempestoso mar, per fragil barca,

al comun porto, ov’a render si varca

conto e ragion d’ogni opra trista e pia.

Onde l’affettüosa fantasia

che l’arte mi fece idol e monarca

conosco or ben com’era d’error carca

e quel c’a mal suo grado ogn’uom desia.

Gli amorosi pensier, già vani e lieti,

che fien or, s’a duo morte m’avvicino?

D’una so ’l certo, e l’altra mi minaccia.

Né pinger né scolpir fie più che quieti

l’anima, volta a quell’amor divino

c’aperse, a prender noi, ’n croce le braccia.

My life’s journey has finally arrived, after a stormy

sea, in a fragile boat, at the common port,

through which all must pass to render an

account and explanation of their every act,

evil and devout.

So I now fully recognize how my fond

imagination which made art for me an idol and

a tyrant was laden with error, as is that which all

men desire to their own harm.

What will now become of my former

thoughts of love, empty yet happy, if I am now

approaching a double death? Of one I am quite

certain, and the other threatens me.

Neither painting nor sculpting can any longer

quieten my soul, turned now to that divine love

which on the Cross, to embrace us, opened wide

its arms.

—Michelangelo, ‘Sonnet 285’

Bill Viola, Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall), 2005

Post Notes

- Bill Viola’s website

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Marie Menken: Arabesque for Kenneth Anger

- Antony Gormley: Sculpted Space Within and Without

- Jordan Belson: Sentience in Celluloid

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Plato: Phaedrus and the Charioteer

- Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames

- Marsilio Ficino: Know Thyself

- Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui & Antony Gormley: Sutra