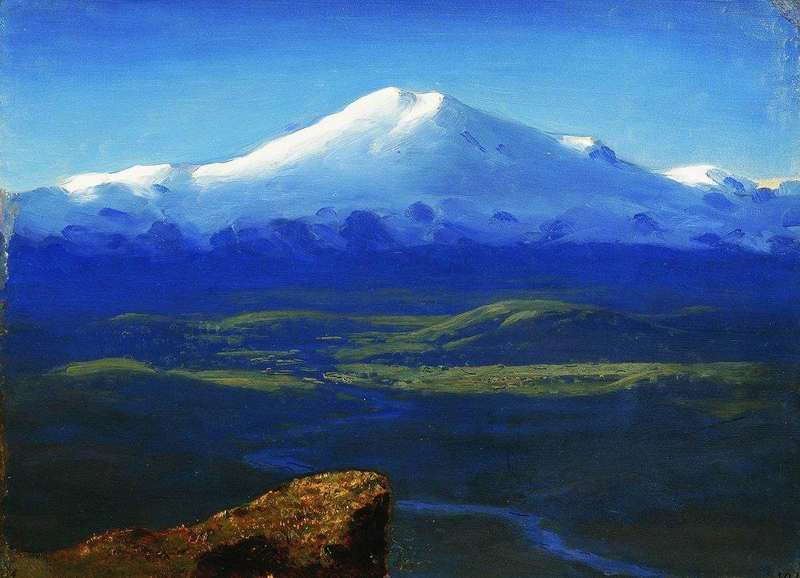

Photograph: [Public Domain] WikiArt

A mountain journal

I asked the boy beneath the pines.

He said, “The Master’s gone alone

Herb-picking somewhere on the mount,

Cloud-hidden, whereabouts unknown.”

—Chia Tao, “Searching for the Hermit in Vain”

SILENCE … Deep, unfathomable, still. I look up at the sky above me. It is intense, cerulean blue—the blue of my beloved grandmother’s eyes; the blue of antique glass jars once traded along the Silk Road; the blue of the plumage of an exotic bird. Then I remember the words of Advaita teacher, Robert Adams: “There is no sky and there is no blue.”

I am sitting atop the majestic Mount Tamalpais, just north of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. Graceful chaparral-clad hillsides undulate down towards Stinson Beach, where I am staying, and the Pacific coast. I feel obliterated in the face of such a vast panorama of overwhelming beauty. The dissonant melody of an insect counts out the hours as I remain a witness to this glorious unfoldment and indeed wonder if all that I behold can possibly be real.

The shimmering heat casts a momentary spell over my senses; the high altitude starts to make me feel unsettled as unfamiliar sensations course through my body and mind. Something is struggling to release itself from the fetters of skin and bone that shroud me in mortality. My inner self is striving to set itself free …

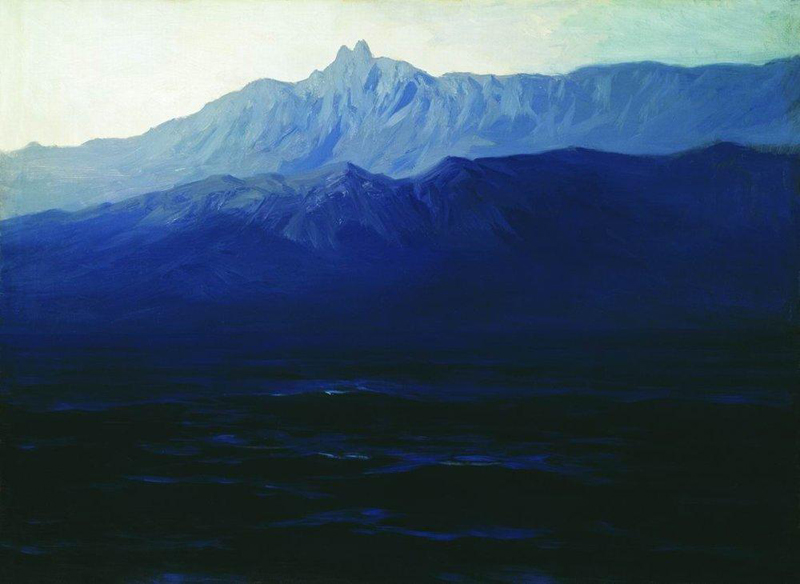

Photograph: [Public Domain] WikiArt

Interested in Asian art and culture from an early age, Alan moved to the United States in the late thirties, becoming an Episcopal priest for a time, eventually settling in San Francisco where he taught Buddhist studies and delivered a regular radio show, Way Beyond the West. Publishing seminal books—The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety; The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are; and The Way of Zen—such was his ever-increasing popularity, he subsequently became the spiritual figurehead—the very embodiment of “irreducible rascality”—of the countercultural Beat movement and undertook a lifetime of travelling and lecturing on the teachings of Zen Buddhism, Hinduism and the Tao.

One such creative endeavour on his alpine retreat was a personal journal, in which he collected his ideas on a vast array of topics dear to his heart, later published as Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown. He also wrote his monograph, The Art of Contemplation, worked on his autobiography, In My Own Way, and composed his final book, Tao: The Watercourse Way, whilst ensconced in his hermetic abode. It would be soon after returning from a whirlwind lecture tour of Europe, Canada and the United States, that Alan passed away in his sleep in late 1973 on the mountain he came to revere.

Photograph: [Public Domain] WikiArt

August 1970

There is the water and now there is also the mountain. (In Chinese, the two characters for ‘mountain’ and ‘water’ mean ‘landscape’.) I have the use of a small one-room cottage on the slopes of the mountain—Tamalpais—which I can see from the ferryboat. It is hidden in a grove of high eucalyptus trees and overlooks a long valley whose far side is covered with a dense forest of bay, oak and madrone so even in height that from a distance it looks like brush. No human dwelling is in view and the principal inhabitant of the forest is a wild she-goat who has been there for at least nine years. Every now and then she comes out and dances upon the crown of an immense rock, which rises far out of the forest. No one goes to the forest. I have been down to its edge, where there is a meadow, good for practising archery, and I think that one of these days I will explore the forest. But then again I may not, for there are places which people should leave alone …There are situations when one owes solitude to other people, if only not to them bother them. But more than this, the multitude needs solitaries as it needs postmen, doctors and fishermen. They go out and they send, or bring, something back—even if they send no word and vanish finally from sight. The solitary is as necessary to our common sanity as wilderness, as the forest where no one goes, as the waterfall in a canyon, which no one has ever seen or heard. We do not see our hearts. I do not expect to be all that solitary for, as a paradoxical person, I am also gregarious and favour the rhythm of withdrawal and return. But in the mountain, I watch the Tao, the way of nonhuman nature (if there is really any such thing) and feel myself into it to discover that I was never outside because nature ‘peoples’ just as much as it ‘forests’.

To realize this one must go beyond what both distinguishes and segregates us as human beings—our thoughts and ideas. To put it in a rather extreme way: we are misled when we believe that our ideas represent or mirror nature as mere observers. The tree does not represent the fish, though both use light and water. The point is rather that our thoughts and ideas are nature, just as much as waves on the ocean and clouds in the sky. The mind grows thoughts as the field grows grass. If I think about thoughts, as if there were some ‘I’, some thinker watching them from outside, there arises the infinite regression of thinking about thinking, etc., because this ‘I’ is itself a thought and thoughts, like trees, grow of themselves. In solitude, it is easier for thoughts to leave themselves alone. It is, thus, a mistake to try to get rid of thoughts, for who will push them out? But when thoughts leave themselves alone the mind clears up.

—Alan Watts, Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown, ‘And the Mountain’

Photograph: [Public Domain] WikiArt

Buy Book

Post Notes

- Alan Watts Organization

- Alan Watts: The Two Hands of God

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Alexandra David-Néel: My Journey to Lhasa

- Hermann Hesse: The Journey to the East

- Edward A. Burger: Amongst White Clouds

- John Adams: The Dharma at Big Sur

- Roberta Pyx Sutherland: Ensō Variations

- Kim Ki-duk: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue

- Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching